Asia Week New York 2019: Bridges to Forgotten Worlds

The world of South and East Asian antiquities is generally very regular. After all, not a whole lot changes when it comes to ceramics and deities from centuries past. That said, this annual March showcase of Asia Week in New York appears to be an unusual one in terms of the discussion around Asian art, possibly inspired by the current political moment.

The most intense example of political dissent is Scholten Art’s exhibition, “Captive Artists: Watercolors by Kakunen Tsuruoka (1892-1977).” The solo retrospective focuses on art made by a self-taught Japanese-American artist during his internment at a camp in Arizona. After an American mandate corralled the ethnic population following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor ten camps were set up around the country—allegedly, for the safety of the American people.

This cultural shift was pivotal, not just on a macro-scale when it came to American attitudes towards a racial diversity, but for the individuals who had previously defined themselves as proud Americans. Overnight, they were encamped and isolated from the lives they had built. The art made during that time inevitably reflected this deep anxiety.

Scholten’s exhibit chronicles this steep decline through one artist’s experience. Prior to his internment, the rags-to-riches story of Japanese art dealer Kakunen Tsuruoka was one of triumph. He successfully sued his art gallery boss for indentured servitude at the turn of the century (how many of us can empathize, I wonder?), and subsequently became a successful eponymous dealer. Tsuruoka’s network was a wide array of American-born intellectuals, and he became known as much for his own art as the works he sold.

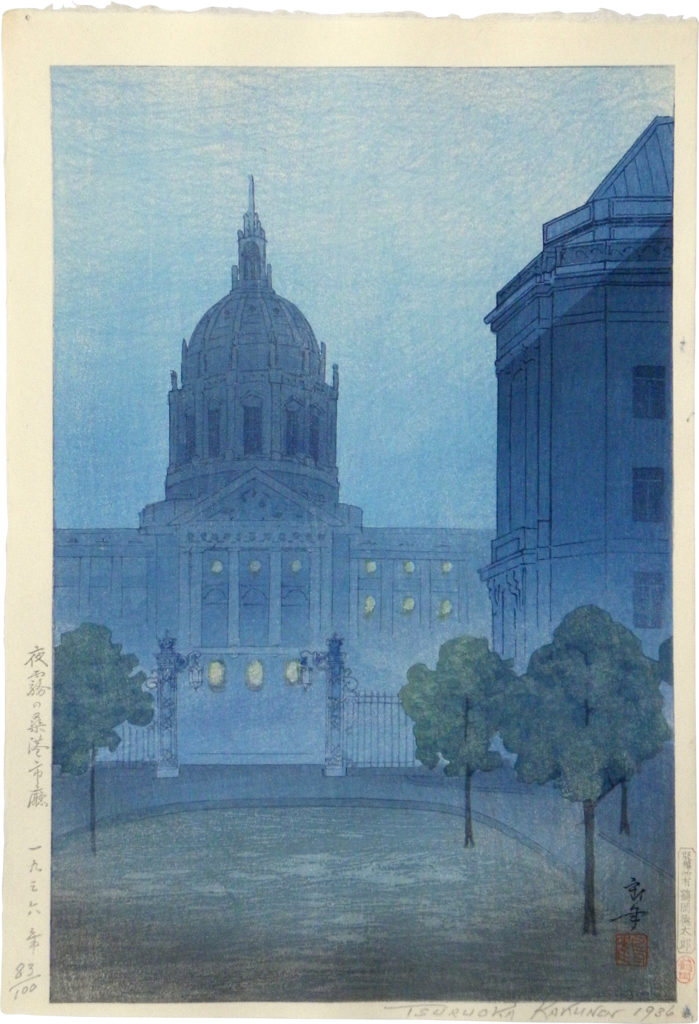

This culminated in his depictions of a strong America. Scenes of his home state of California utilized Japanese printing techniques to exemplify the industry and the landscape. Quite literally, they were a bridge: “Night Mist Over San Francisco City Hall” (1936) and “Golden Gate Bridge in Fog” (1937) were some of these beautiful scenes.

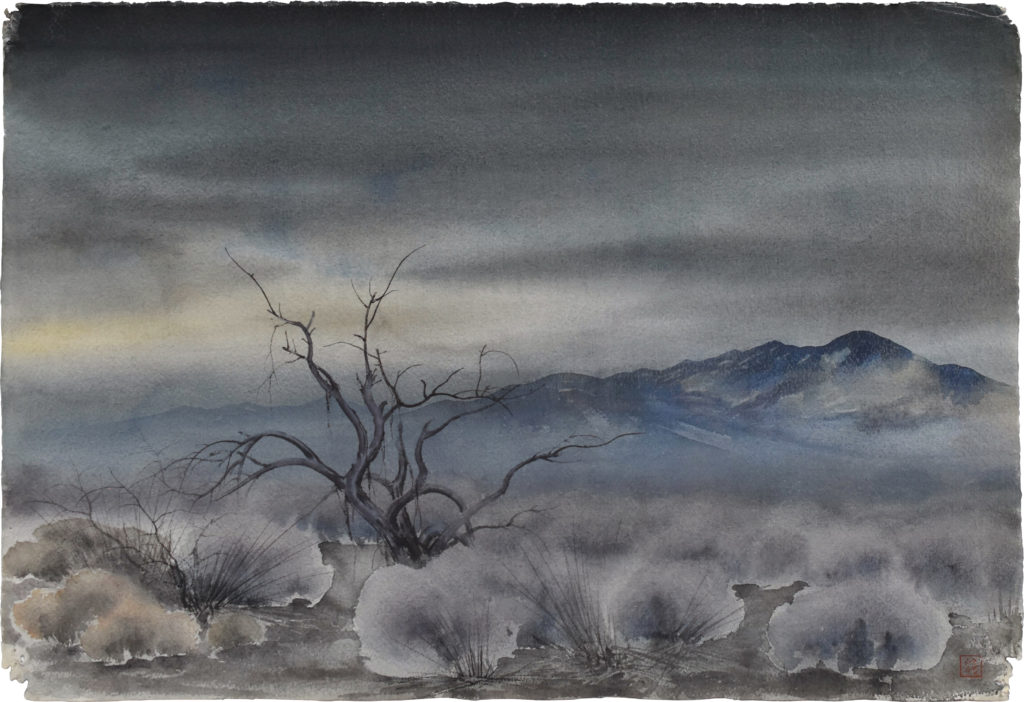

Previous: Tsuruoka Kakunen, Untitled (dark sky over mist on mesquite and brush), watercolor on paper, with artist’s seal “Kaku,” ca. 1942-44, 15 1/8 by 21 3/4 in., 38.3 by 55.4 cm. Above: Tsuruoka Kakunen, “Night Mist Over San Francisco City Hall,” 1936.

But then Tsuruoka was interned. His former boss, by then a colleague, named T.Z. Shiota, posted a harried but poetic goodbye on his gallery door: “At this hour of evacuation when the innocents suffer with the bad,” he wrote “We bid you, dear friends of ours, with the words of beloved Shakespeare ‘PARTING IS SUCH SWEET SORROW’…Till We Meet Again, T. Z. Shiota.”

The art reflected this deeply tragic rupture. Desolation spurred images devoid of any living things—dead, barren landscapes lacked the vivacity of his former works. Some of the most striking works are untitled. “Dark Skies Over Mist” and “Poston After Dark” were assigned after the fact, attempting to give name to feelings of hopelessness.

…it underscores the remembrance of the troubled histories that define America, that we must learn from to stay safe and proud.

In spite of everything, they were celebrated in their tragedy. Five were gifted to the camp administrator, and are still in federal museums today, and his camp murals were featured in a book called “Beauty Behind Barbed Wire” in 1952. Given that this exhibition follows the recent government shutdown that closed American museums, and comes in a time of deep tension in a current administration undoubtedly characterized by xenophobia and unease, it underscores the remembrance of the troubled histories that define America, that we must learn from to stay safe and proud.

But the explicit contrast of art versus power extends beyond the 20th century at this year’s Asia Week. From the bridges of California at Scholten Gallery, Galerie Hioco presents a tempera painting of Thang-stong rgyal-po, the 15th century Tibetan bridge builder, in a tempera on canvas from Central Tibet. The 1981 dissertation of now-Harvard professor Janet Gyatso explained his life and times.

Thang-stong rgyal-po, Central Tibet, tempera on canvas, late 16th – first half of 17th century, 83 x 64 cm or 32 3⁄4 x 25 1⁄4 in.

The chronological evolution that led to Thang stong rgyal-po’s rise to spiritual power and renowned was based on connectivity. As Buddhist religious power was centralizing, the need for literal crossroads in terms of bridges and roads was necessitated. That’s where our friend Thang came in. A builder of iron chain suspension bridges, he was passionate about equalizing social and religious gains. Gyato quoted him as saying:

“I [want] all the sentient beings that are seen, heard, thought of, or touched, to enjoy the glory of a good birth and to be established on the highest level, the definitely auspicious insurpassible enlightenment… in lonely places to protect against the fears of robbers and demon bandits, and in the narrow paths and water ways where gods, ghosts, and men travel.”

Navin Kumar Gallery’s exhibition also addressed that Tibetan theology was fraught with power struggles and political intrigue. Called “Technologies of Self,” its focus was the lesser-known 16th century Tibetan Buddhist scholar and teacher Sherab Özer, whose depiction in “8 Chariots of Spiritual Accomplishment,” provided a distilled guide to this cultural moment in philosophy. The positioning of the figures was completely strategic to elevate Özer’s own status in the network of well-to-do Tibetans.

Sherab Özer, Central Tibet, distemper on cloth, ca. 1600, 66×50.8 cm.

Furthermore, one section of the 18th-century “Miracles at Saravasti” shows “Leaders of Six Rival Traditions in Anguish” —essentially, nonbelievers and the consequences of their lack of faith. Haggard and forlorn, they weep in agony at the bottom of the page. The message is clear: you were in or you were suffering, even in the serene world of Tibet.

18th Century, Central Tibet, distemper on cloth, 91.5×66.1 cm (image), 173.4× 96.3 cm (with silks).

To be sure, Hioco’s choice to show Thang-stong ran counter to this discourse. His passion for the common man came from a lifetime of bristling against authority. As a child, he was giving initiations to farm animals, and only wrote a single prayer at school to the dismay of his teachers. But soon his great talent was revealed through his life as a bridge builder. While wandering in a time of centralization, he relied on this sense of otherness to learn and connect with new people, performing religious rites (austerities), even to the detriment of his own reputation. On one occasion, he was beaten by monks who found his religious choices affronting.

It was borderline-anarchist for a Tibetan spiritual leader. Gyatso quoted him as saying in his youth:

“I am a madman with no direction.”

However, in time, his mysticism caught the attention of powerful families, and he was inevitably praised as the years went on. He lived to be 128 years old, and counseled others on his longevity.

At its worst, Asia Week New York can feel fragmented—a hodgepodge of art from around the continent, spanning thousands of years and with suspect provenance and plenty of opportunities for counterfeits. But despite the overwhelming nature of the scale and sophistication of the exhibitions, it is the stories that propel the legacy of the works on view. In this case, the connections over hundreds of years from Tibetan to Japanese America smart of painful relevance today, in a time of violent and traumatic leadership in American history. The next time you look at a 16th century Tibetan hanging scroll or a 20th century Japanese woodblock print, perhaps you will remember the impact of the lives that brought the work to fruition, and the enduring realities they continue to represent.

Asia Week takes place between March 13th and 23rd in New York. To see a list of participating galleries and institutions please consult their website.

Related Articles

Indian Art Highlights: Linking Contemporary with Ancient at Asia Week

What's Your Reaction?

Editor-at-Large, Cultbytes Alexandra Bregman has written for The Wall Street Journal, Architectural Digest, The Art Newspaper, and the Asian Art Newspaper among others. She began her career with internships at Christie's and Gagosian gallery 10 years ago, later traveling to India and France for work and ghostwriting for a global CEO. Bregman spent time at Université Paris IV-Sorbonne, and completed degrees at Smith College and Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. l igram |