Tuesday Under Ten: How Art Works Under $10,000 Sustain the Art World

Every Tuesday for the past year, I have posted on my website and to social media, a work of art I love priced under $10,000. I find it rewarding to work with collectors who set a $10,000 annual budget and buy one piece a year, slowly building a thoughtful and meaningful collection over time. That said, if I counted on my under-$10,000 clients, I would not be able to earn a living as an art advisor. However, working with art at this price point is a way for me to give back to the art community.

My hope is that reading about a record price achieved for, say, a Basquiat, will lead the reader to turn to someone like me—an art advisor—to inquire what she could own that fits in her budget.

In light of art market trends that have made it increasingly difficult for low to mid-market galleries to stay in business, support of emerging artists and artists whose works sells at a lower price point is particularly important right now. A shocking number of galleries have recently shuttered, including in the past two years in New York: Andrea Rosen, CRG, Feuer/Mesler, Kansas, Lisa Cooley, Lombard Fried, Mike Weiss, Mixed Greens, Robert Miller, and Tracy Williams. Sarah Douglas writing for Artnews, calculated that between 2012 and 2015 only 12 galleries closed, while since 2015 the number skyrocketed to 46, including 31 in the past year. These closures and the financial pressures faced by all but the biggest galleries are getting headlines in art publications and even in The New York Times. The articles blame growth of the international mega galleries (like Gagosian, David Zwirner, and Pace) alongside the increasing draw of the “trophy” artists they show. They also point to the breakneck speed of the nearly annual global art fair calendar and the rising rents in gallery areas like West Chelsea. I agree that these are significant factors in today’s art market, but I would like to suggest that both could present an opportunity rather than a problem.

Previous: Alexa Williams and Crystal Gregory, Eve, 2016, handwoven cotton and concrete, 50 x 54 inches. Courtesy of the artists. Photographed by Alexa Williams. Above: Peter Kayafas, North Dakota, 2010, Gelatin Silver print, 16 x 20 inches. Courtesy the artist and Sasha Wolf Projects, New York.

First, yes — the value of artwork is often fetishized. Just about the only time the Contemporary art world gets a non-art publication headline is when a breath-taking price is achieved at auction. Art as commodity seems to grab interest over content and meaning. Although there’s been some pearl clutching about this journalistic phenomenon, I find it a source of hope. If thinking about dollars and cents catches attention in a way brushstrokes do not, then fine. My hope is that reading about a record price achieved for, say, a Basquiat, will lead the reader to turn to someone like me—an art advisor—to inquire what she could own that fits in her budget. There are plenty of people who can spend $10,000 or $50,000 a year, and there is nothing they can afford at Gagosian. The issue is reaching these collectors.

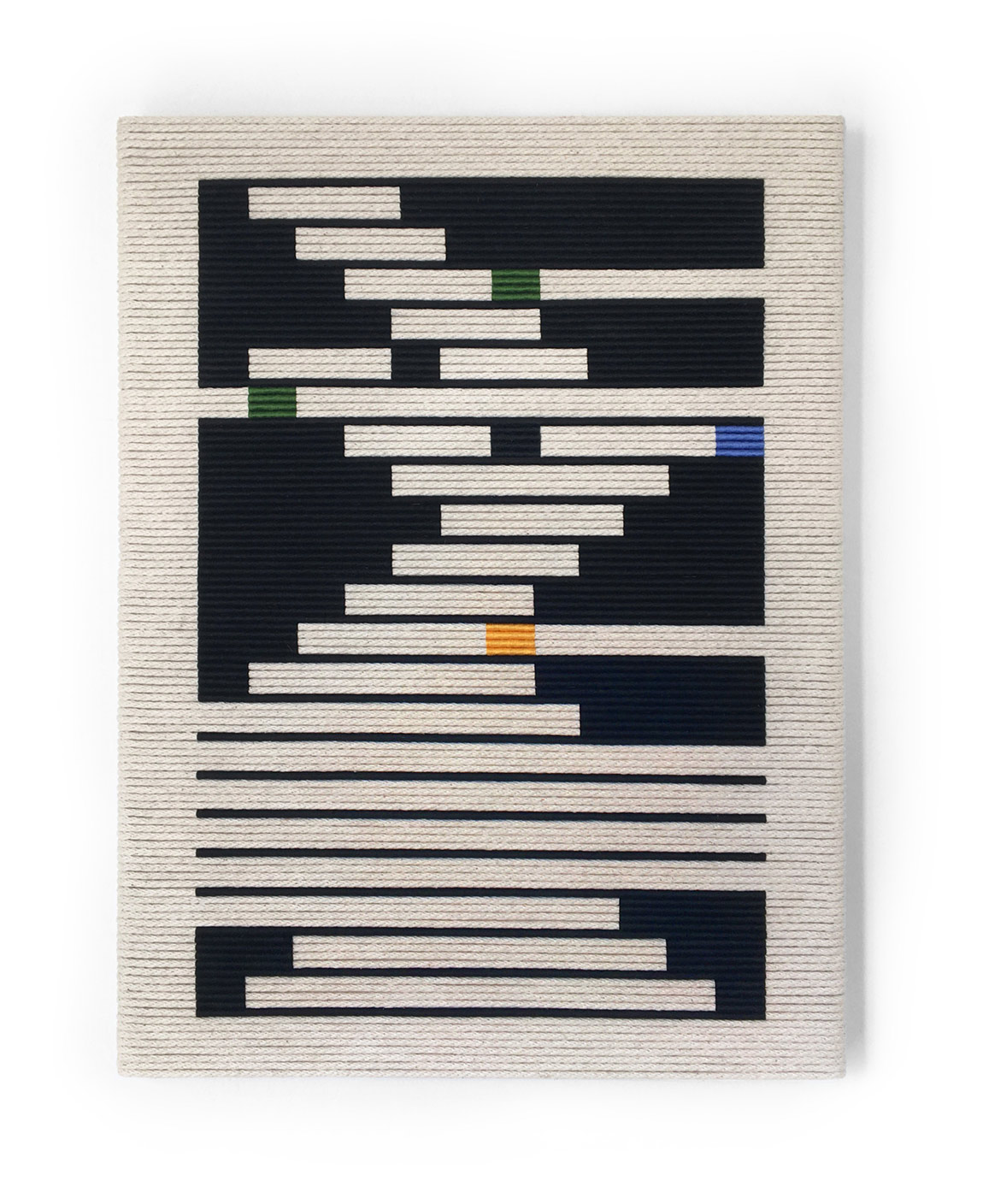

Senem Oezdogan, Momentum II, 2015, Wood, rope, and cotton, 24 x 18 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Uprise Art, New York.

So, second, love them or hate them, art fairs across the world are packed, drawing people from many walks of life. And, with approximately 270 art fairs around the globe each year, there are 200 more than there were a decade ago. Fairs, however, are a huge financial gamble for a gallery. The starting price for a small booth at a second-tier fair, can be as much as $10,000 (and note, a big booth at a top drawer fair, can cost as much as $100,000). To do an art fair, a dealer must also pay for booth extras (walls and lights at a minimum), shipping the art, and airfare and hotels for staff. Undertaking these risks is often necessary to get work by your gallery artists in front of art-buying eyes.

As an art advisor, art fairs are invaluable tool for me. My clients are busy people for whom art buying is a secondary priority. As much as I know they enjoy looking at art with me, it often takes a backseat to professional and family demands. Since I have a hard time scheduling in-person viewing time with my clients, being able to show them a huge variety under one roof within a few hours is amazing. They can learn so much about what they like and what is available quickly. My clients often make multiple purchases in an afternoon that would have taken months with digital images and gallery visits. However, the less expensive the art work a gallerist sells, the harder it is to undertake the expense of an art fair. And, because galleries are taking on such tremendous costs, they are less likely to show work by their younger unproven artists, or artists whose pieces are at a lower price point.

Ryan Nord Kitchen, Installation View at The Armory Show, 2017. Oil on linen, 24 x 21 inches each. Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York.

The less a gallery is paying in rent, the more they can risk on an art fair, showing less expensive work by younger artists. I think dealers like Sasha Wolf (of Sasha Wolf Projects) and Candice Madey (of On Stellar Rays) have it right. They both closed their ground floor gallery spaces in favor of office showrooms so they have the time and resources to focus on art fairs and other one-off projects. For galleries I see the shift from a permanent brick and mortar location to art fairs to be an opportunity. The day-to-day staffing of a retail space is a drain on time and resources, and so often during the 10am to 6pm gallery day, there is not a single set of eyes taking in an exhibition. 65,000 pass through the Armory Show every year and over 70,000 visit Art Basel Miami Beach. It may be a four day exhibition, but the reach is far beyond what most galleries bring in for a show. By paying less rent every month, a dealer can do more fairs and take advantage of some to show riskier or less well-known and less expensive work.

Bayne Peterson, Apollo, 2016, Dyed plywood, dyed epoxy, 14 3/8 x 8 x 7 1/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Kristen Lorello Gallery, New York. Photographed by Jeffrey Sturges.

So, why is this important? Sales allow artists to make art. Full stop. The value for me in promoting less expensive artwork is twofold. First, the ability for artists to earn a living by selling works of art allows their artistic practices to flourish. It is hard to make good work when you are an artist-slash-whatever and your studio time is tucked into evenings and weekends. Like any creative or philosophical pursuit, creating art requires time and concentration to pursue an idea and connect one thought to another. Second, I believe that living with good art—regardless of the cost—improves life, broadens perspectives, and stimulates thought. When a client tells me that they spend time every day with a piece I helped them purchase, I am thrilled. I hope that my “Tuesday under Ten” series helps people to think of art as something attainable rather than aspirational. Some of my clients do not have six-figure art-buying budgets, but that doesn’t mean they can’t live with wonderful works of art.

Follow Amy Snyder’s “Tuesday under Ten” every Tuesday this month on Cultbytes Instagram.

This article was also published in Amy Snyder’s Chronicles.

What's Your Reaction?

Content Collaborator, Cultbytes As an art advisor, Amy Snyder advises new and seasoned collectors on the acquisition of Contemporary art by both established and emerging artists. A Manhattan native, Amy is a graduate of Amherst College and received her Ph.D. from the Bard Graduate Center. She has held positions at several galleries in addition to Sotheby’s and a leading art advisory firm. Although based in New York, Amy has clients across the United States. l igram l twitter l website l