Franck Chalendard: “Manger des olives et faire l’amour” – Ceysson & Bénétière, NYC

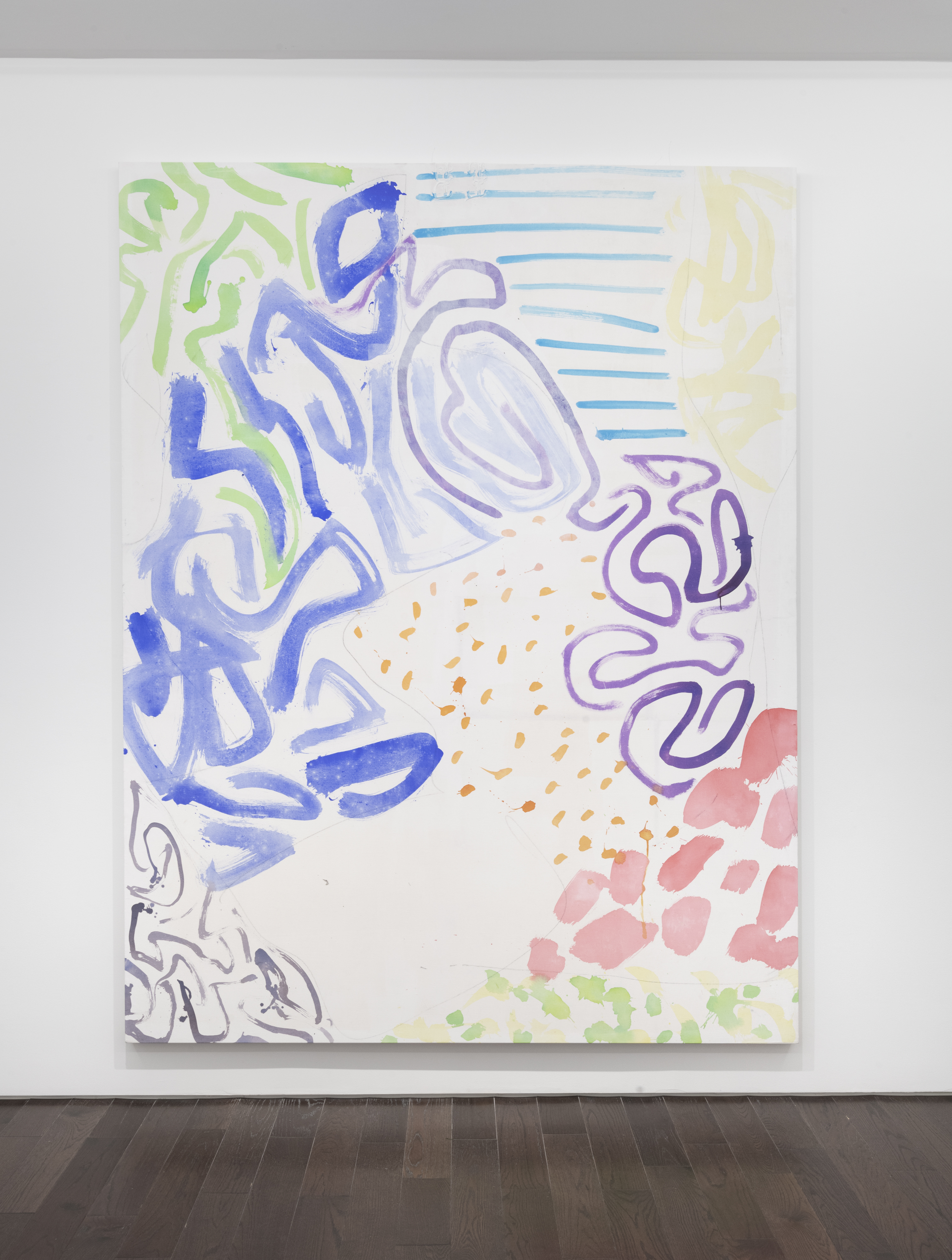

For his first solo show in New York, the French painter Franck Chalendard created a series to evoke a sense of spring, desire, and whimsy. With groupings of lines, circular gestures, grids and splatters in vibrant color he tried to find an equilibrium between lightness and freedom on his canvas. He gave the series the suggestive yet modest title: “Manger des olives et faire l’amour.”

Chalendard has been painting for some 25 years, but his practice does not follow a distinctive style, except, perhaps most poignantly, for its constant reinvention. With each body of work, he experiments with a new painting technique, material, motif, or color scheme. After modernism, he believes, that it is near impossible to innovate painting – yet he seems to succeed every time.

Previous: Installation view. Above: Franck Chalendard, “Manger des olives et faire l’amour #7.” Acrylic on canvas, 100×80 cm. All photos courtesy of Ceysson & Bénétière if not otherwise noted.

Previous: Installation view. Above: Franck Chalendard, “Manger des olives et faire l’amour #7.” Acrylic on canvas, 100×80 cm. All photos courtesy of Ceysson & Bénétière if not otherwise noted.

The novelty, in these fourteen works, is his use of old white sheets collected from friends and family, as his canvas. Normally he would edit a canvas by painting over it. However, to keep the features of the thin textile Chalendard has cut and pasted using a clear adhesive as a form to create the final expression. The choice of material and act of editing shifts the works from the realm of painting to objects, or somewhere in between.

The colorful and visually striking series initiates a haptic experience. The functional aspect of the bedding brings the viewer closer to the bodies of those who have previously lived between the sheets, or canvases, as it were.

Amy Elkins, “Handmade Jump Rope (torn and braided bed sheet),” 2009-2016, Archival Pigment Print, 40×16 in. Edition 5/5. Courtesy of Mark Moore Fine Art.

A similar, albeit much darker, link to the body is present in Amy Elkins photo series “Black is the Day, Black is the Night,” depictions of the material culture surrounding men serving time in maximum security prisons in the United States. One work features a torn sheet braided into a jump rope, made by an inmate on death row. Imagine the man, stripped of his freedom, creating a tool to exercise through the laborious act of tearing then braiding. Then, imagine him skipping in his small confined space, sweat absorbed by the sheet. He was executed in 2012.

As a reminder that Chalendard’s paintings are the sensations they bring to their viewer, the art historian Romain Mathieu writes: “Make no mistake, for behind the apparent detachment of these paintings, it is about what painting does to us, the effect it has on us physically and thus it is about its essentials, that is to say, its desire.”

Given the physical and intellectual labor put into the work and the deliberation of each brush stroke, it seems incorrect to call them simple, however, they are certainly playful.

Chalendard wanted the use of sheets as a canvas to bring out a sense of simplicity in the works. When creating these paintings, he had in his mind the “naïveté of a child,” he said, “freely painting on found surfaces.” Given the physical and intellectual labor put into the work and the deliberation of each brush stroke, it seems incorrect to call them simple, however, they are certainly playful. Reflecting Chalendard’s temperament and, perhaps, his present disposition to painting itself.

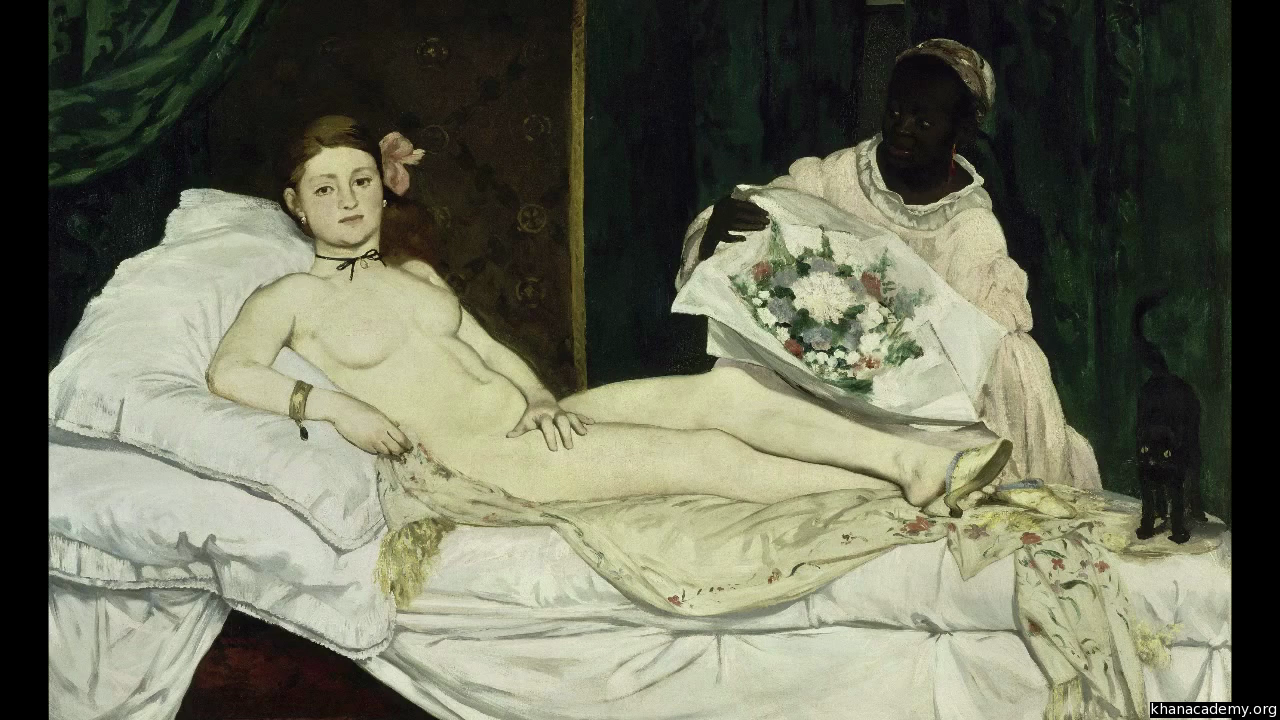

Edouard Manet, “Olympia.” Oil on canvas, 130×190 cm. ©RMN, Hervé Lewandowski

Edouard Manet, “Olympia.” Oil on canvas, 130×190 cm. ©RMN, Hervé Lewandowski

Actual depictions of sheets have scandalized viewers in the past, linking the work to eroticism. Take the pulled up bed sheet in Gustave Courbet’s “The Origins of the World” which famously reveals a woman’s sex. The sheet itself is as important as her bush. She is not like the many depictions of the biblical story of Adam and Eve in a garden, frolicking freely, she is in bed with or waiting for, a lover. In another scandalous picture of the time painted by Édouard Manet, Victorine Meurat poses as a courtesan reclining, naked, on a bed of rumpled bed sheets. It is alleged that the painting was hung out of reach from offended men who tried to strike it with their canes. The painting, titled “Olympia,” was modeled after Titian’s “Venus of Urbino”(1534) that in turn was derived from Giorgione’s “Sleeping Venus” (1510), the first reclining nude in history. Both feature Venus lounging on creased drapes or sheets – the fabric suggesting the women are exposed in their most intimate environment, the bedroom.

Franck Chalendard. “Manger des olives et faire l’amour.” Acrylic on canvas. 2019.

Franck Chalendard. “Manger des olives et faire l’amour.” Acrylic on canvas. 2019.

Chalendard’s replacement of the canvas with bed sheets inextricably and un-mistakenly links the works to intimacy and desire, both concepts that today are decidedly less scandalous than when the mentioned reclining nudes were painted. Instead of explicit depictions of sensuality, the abstract paintings beckon you to let your imagination roam. In some works, I see forms resembling those of Henri Matisse (who also worked with collages and cut-outs). Languishing on a picnic blanket on a summer’s day with a lover or an Instagram worthy sunset are other scenarios that gently pass by.

I say Instagram worthy because Chalendard’s use of color is on trend. Ultra Violet, Greenery, Rose Quartz/Serenity, Marsala, Radiant Orchid, and Emerald Green were chosen as Pantone’s most recent ‘Colors of the Year.’ With the exception of Marsala, Chalendard has used shades close to them all. It is daring for an artist to bring a color palette overused by designers, advertisers, and brand consultants into the gallery space. But, it is this layered complexity, masterfully including the subtle dialogue with popular culture, that adds to the allure of the work.

Although this delicate series that marks the artist’s American debut aims to evoke simple sensations of pleasure it is clear that Chalendard’s practice is based a deep understanding of the history of painting and a desire to construct something new.

***

“It was important for us to introduce Chalendard’s work to North America early in our programming here,” said gallerist François Ceysson, who together with Loic Bénétière founded Ceysson & Bénétière in Saint-Étienne in 2006 (they opened the New York outpost in 2017). Early on, François’s father Bernard Ceysson joined them as an advisor. Ceysson senior is a serial museum director (among them Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris). Ceysson senior helped build the collection of work by the Supports/Surfaces movement at the museum of modern art in Saint-Étienne. Suitably, Ceysson & Bénétière represent many of the artists from the movement. Chalendard is not a Support/Surface artist per se, but he is a friend of one of its main protagonists: Claude Viallat. Chalendard’s use of sheets, unconventional material, links directly to conversations between the two artists.

Ceysson & Bénétière is fuelled by intergenerational dialogue, not only in art making but also in art dealing. The New York branch is headed by Ellie Rines, founder of 56 Henry and listed by artnet as a young art dealer to watch in 2015. Together with François, Loic, and Bernard she has come up with the New York program that, as evidenced by Franck Chalendard’s “Manger des olives et faire l’amour” brings fresh art by established artists to the Upper East Side.

Franck Chalendard: “Manger des olives et faire l’amour,” is open through July 31, 2019 at Ceysson & Bénétière, 956 Madison Avenue, New York NY 10021, USA.

You might also like

Méïr Srebriansky: Nietzsche, Abstraction, and a Hint of Mickey Mouse

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.