Physicality: Negotiating Place/Site/Geography in Art During Lockdown

During the pandemic lockdown, I had the pleasure to chat with Alasdair Asmussen Doyle, a Tasmanian artist from a sailor family who is now based in Western Europe. The ocean is a recurring subject in his work. We started this exchange during lockdown to reflect on our understanding of the role of place, site, and geography in art.

Edy Fung: How has it been to survive as an artist during lockdown?

Alasdair Asmussen Doyle: I have been fortunate, inasmuch as that my doctoral work has offered some consistency and stability during this period, and forced a degree of activity that I am not sure would have otherwise existed. Nonetheless, I feel the precariousness of being an artist at this time, and a difficulty in re-situating a practice that typically locates itself in spaces beyond my immediate surroundings, to the confines of lockdown.

It has nevertheless felt like a fertile time for thinking about future trajectories, and how art, and its physical presence, positions itself in a landscape that is increasingly hinging on the digital. While the impetus to move exhibitions and artistic discourse to virtual forms, has ultimately rendered the absence of a ‘being there’, it has also shown how domestic spaces can be reimagined as places for the production, presentation, and engagement of art.

EF: Certainly, we’ve been hearing comments that this crisis will change the way people live (especially younger generations), in either direction i.e. ‘we will value more of our physical experiences coming out on the other side!’, or ‘we’ll work and socialise more online because we’ll have been shaped by those patterns.’ For me, I don’t think a mere online work can achieve a meaningful narrative without support of the real environment. But, the virtual space can be a small part as the prompt to leave the more important role to the human mind to imagine the rest of the work. Does that make sense to you? I think this is what makes your work —that drifts between geographic, ethnographic, and cartographic indications —both hypnotic and affective.

AAD: I think that this assumption that the viewer plays an active role in the construction of meaning in a work, is an idea grounded in conceptual art. When I think of some of the figures that felt seminal in my own arts education, such as Francis Alÿs, they were all very good at initiating ‘gestures’ that the viewer subsequently completed in one form or another. In my practice, whether it is works such as ‘Where I am not’ or ‘100ft of sea’, there is equally a distinct space of absence, left for the viewer to project themselves into.

EF: Your piece ‘Where I am not’ is about your expedition to the furthest point from your birthplace. Can you expand on what makes you hooked on the idea of antipodes? What do you think you would expect to feel if you did make it to the point in the expedition?

AAD: Prior to coming across to live and work in Belfast, I undertook an MA at the Royal College of Art in London. Although I had previously resided in Europe, this time, inhabiting another island on the ‘other side’, I found myself considering more the personal and historical associations that these places share with my home country of Australia, and situating myself as a ‘European Australian’ between these two poles.

At some point, I came across the writing of New Zealand author Mathew Boyd Goldie, that discusses the various presentations of the antipodes. Although the term has largely come to be associated with the ‘South-East’, —some islands off the coast of New Zealand were even christened ‘Antipodes Islands’—, the origins of the term articulated less fixed sites, but rather a relationality of things diametrically opposed to one another; as one place has its antipode, it too is antipodal to another. Goldie expresses within the idea of antipodes a landscape devoid of any hegemony, but hybrid and multiplicitous.

It felt imperative, and perhaps inevitable, that I would attempt to visit the point opposite my birthplace — situated in the North Atlantic. In part, the endeavor was encouraged by an impulsivity, but also the recurrence of several ideas, stemming from an increasingly nomadic life, and lingering questions of identity, belonging, and home — how do we situate ourselves in progressively transient spaces? To pursue for the point opposite my birthplace expresses a desire to demarcate boundaries, home and its antithesis; two sites linked through the idea that to maintain a consistent direction past the antipode, inevitably leads to a coming home; a potentially endless cyclical process — such are our spatial limitations.

The trip itself was ultimately unsuccessful, we were left stranded without wind several hundred miles from our intended destination. Nevertheless, the remnants extracted from the undertaking, a 16mm film, logbook, and the waiting place of four photographs, felt no less meaningful because of it.

EF: The desire to reach the furthest point on earth from your birthplace, metaphorically the least familiar place, can be easily comprehended. Coming from Tasmania, have you encountered any experiences where interesting perception was casted on your geographic origin?

AAD: Another recent project of mine, ‘The Other Island’, records my efforts to find and document a colony of wild wallabies on the Isle of Man, a marsupial found commonly around Tasmania. Similar populations previously existed across the UK. They are residues of a colonial legacy of transporting, ordering, and displaying distant flora and fauna. However, few adapted to their new environments. The some 150 that have grown in number over the years on the Isle of Man are unique in this sense, revealing the ability to negotiate and inform a new island ecology. The experience of viewing their distinctive outline and motion, transplanted in a Manx landscape, offered a palpably uncanny perception; two places coming together.

During lockdown, I have been reading about Phantom Islands, and an archipelago of islands situated south of Tasmania called the Royal Company’s Islands, that made their way onto maps for decades, but never actually existed. What I find particularly compelling about these islands, is that it still remains unclear when and how they were first mapped. It was only after numerous expeditions decades later, in search of them, that they were cartographically removed. Similar stories are surprisingly common.

EF: Can you share a bit of your previous research on cartography and world mapping, and how the result has informed your current Ph.D. practice?

AAD: My MA dissertation, titled Poles, was a means of thinking through why maps maintain a belief of objective representation, and how we have become so accustomed to hegemonic ways of seeing. I am interested in how the standardization of contemporary maps find their roots in the power dynamics of the past; such as the Mercator map, which had originally been titled the ‘New and more complete representation of the terrestrial globe properly adapted for use in navigation’. For me, it is not solely about the dubious history of mapping embedded in power structures, but also about the possibilities of how we relate to places. In contrast to contemporary states and uses of maps there was, pre-Renaissance, a heterogeneity to cultures of mapping and cartographic outputs; often poetical, emphasizing the relationality of space and a more cosmological approach that accents the importance of giving space to an ‘unknown’. My current doctoral work stems from a similar field of inquiry, however with a particular interest in how moving-image practices construct and communicate geographies to be navigated.

EF: I really appreciate the material sensitivity in a very important piece of yours – ‘100ft of sea’, manifested as both a film and an object. Again, one can perceive your intertwined relationship with the ocean, a recurring entity and a symbolic medium always present in your work. The act of remembrance expands from the personal to the umwelt. Through incorporating the material process and awareness of filmmaking, the idea of memory is transformed into a tangible record which is frozen but can be resurrected when the film is played. What were your thoughts while creating this work? And, in relation to your last works created in 2019, pre-pandemic, do you see this work pivoting a change in direction within your landscape of art-making?

AAD: ‘100ft of sea’ came out of a conversation I had with my father about two events that occurred in the late 90s — my grandmother’s death at sea and my father departing from his research in lung health. I had initially wanted to forge an association between the two, both marked by the breath, however felt increasingly compelled to make a work about my grandma’s passing.

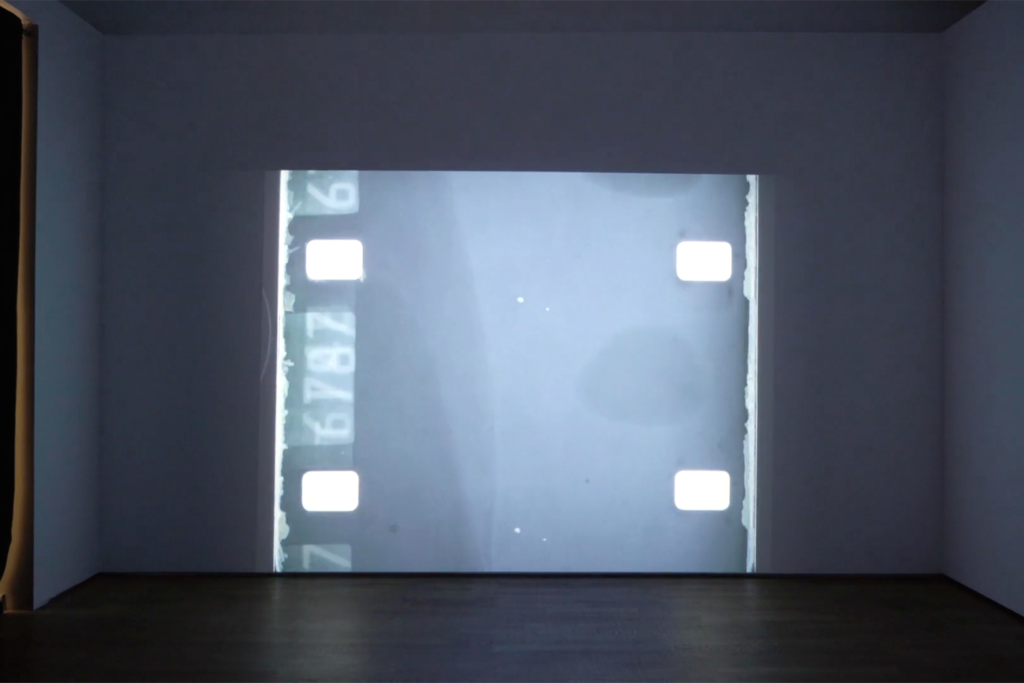

It was made for a show (By the edges of our absence) at Casino Luxembourg, that discussed the margin between presence and absence. On one hand, the work does not reveal anything within a conventional filmic sense, an erasure of the image, but on the other, materially embodies a place that finds its way into the projected sequence of images.

It represented a deviation from earlier work, as it was the first time that I produced a moving-image work without the use of a camera and through a process of inscribing material properties onto a 16mm film-strip. Presenting the physical film, alongside its projection, enacts a mediation between the relationship of the medium as the presentation of images, and as material object. The measurements of the wooden box that house the film correspond to those of the standard dimensions of a coffin, metaphorically encasing a filmic and corporal body.

It is hard to say what effect ‘100ft of sea’ and the material focus of image production will have on my practice. Having emerged, and now re-entered lockdowns in Northern Ireland, the biggest shift for now has been working through the pandemic, and the clear practical limitations, such as mobility, it has rendered. Two new projects that I have recently commenced, have this in mind, locating themselves in Belfast and its immediate surroundings.

EF: I have a feeling already that the freedom and convenience of mobility across the globe pre-2020 will become a retro style of life, especially when as are based on the edge of Europe. The themes you explore and the analog tools you work with, allow you to make art that is incredibly precious, even impossible in the not-so-far future.

AAD: My supervisor at the Royal College of Art had often talked about nostalgia in relation to my practice; I think I like that. I sense there are two prevailing trajectories within contemporary art practice: one that reflects on potential futures and one that ‘looks back’ to reimagine histories. Catherine Fowler writes about this pull to the past, within recurrent approaches to artist moving-image work that for her include, “look[ing] back at moments that have now passed”, a “sense of loss” and an ambition “to break film down as if to reduce it to its most fundamental component.” As an artist thinking about the representation and materiality of place through moving-image practices, it feels instinctual to strip the medium down to its bare bones; to its genesis and cultivation of a new form of travel, that is at this moment of crisis, untenable.

Alasdair Asmussen Doyle is an artist and researcher, currently working and living in Belfast, Northern Ireland, where he is undertaking a Ph.D. at the Belfast School of Art in partnership with aemi (Dublin).

You Might Also Like

Artists on Coping: “Having a Voice Means Listening Up” Reece Cox

Interventions in Public Space: A Conversation with Allard van Hoorn

What's Your Reaction?

Edy Fung is an artist, musician and independent curator from Hong Kong who has lived and worked in London, Tokyo, Lisbon, and Derry. She holds an MA in Curating Contemporary Design from Kingston University London and an MA in Architecture from the Royal College of Art. Past collaborators and partners include ACNI, British Council NI, Catalyst Arts Gallery, CuratorLab Konstfack, DAS Belfast, Derailed Research Lab, Flax Art Studios, Hong Kong Art Centre, LAAB, Lisbon Architecture Triennale, Sonic Arts Research Centre, Visual Artists Ireland. l Instagram l Twitter l Website l