How Much Snark is Too Much? A Response to RM Vaughan vs. Jerry Saltz

Since the rise of the Internet, the number of blogs and online publications has increased – as a result they can cover more ground. In February, ArtFCity.com published a negative review (No Paintings For Old Men: I am Done With Amy Feldman) authored by RM Vaughan which Jerry Saltz dispelled as snark. As a critic myself, this rebuttal between two controversial critics lead me to ask how much snark is too much?

Tracing the origins of the word critic, its usage came to envelope one who evaluates works of artistic merit in 1600. But, scholars, artists, and art historians have long played an important role in taste forming and taste re-enforcing by condemning, touting and categorizing art using different methods. The history of art criticism can be traced back to Pliny the Elder’s Natural Histories, which contain passages on the development of Greek sculpture and painting. A little later, in 6th century China, Xie He described an artistic canon in Six Principles of Painting. Nearly a millennium later, the artist Giorgio Vasari, author of Lives of the Painters, later criticized by Winckelman for its cult of artistic personality, established primarily Tuscan artists as a model for the artistic canon, which remained a significant feature in art history for many centuries. Today, the critic is separated from the art historian: they inform the public, stir debate on art, provide opportunity for public discourse, and share their opinions.

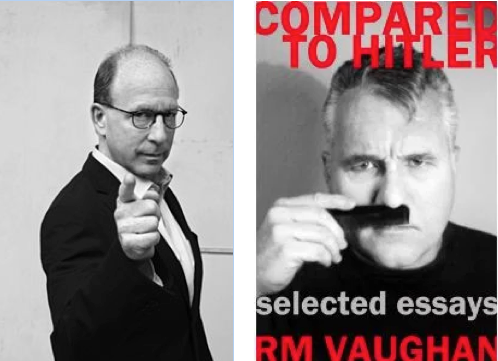

Previous: Amy Feldman at Blain Southern Berlin, photograph courtesy of the gallery. Above: Left: Jerry Saltz, Right: RM Vaughan

For example, in the recent damning review of New York artist Amy Feldman’s show at Blain Southern Berlin by RM Vaughan published on ArtFCity.com, the writer likens her canvases to “paintings that appear to have been made by a ward of distracted Thorazine swallowers who ran out of brushes” stating that “on the other hand, when you can make an international and profitable career out of painting like you’ve never seen a painting before, why wouldn’t you?” before summarizing his thoughts with “The works have no redeeming qualities other than as oversized examples of how shitty and decadent times have become.” The harsh judgements on a relatively unknown painter were corroborated and affirmed by many of the comments left on the forum. However, the discussion peaked in interest when the review caught the attention of New York Magazine’s Jerry Saltz who responded to it through his much-followed Facebook feed where after praising the artist’s work, form and palette as “enticing, smart, original”, he criticized the cynicism in the review.

“It’s not a critic’s job to be right or wrong; it’s his job to express an opinion in readable English.” – Harold C. Schonberg

The role the critic plays is that of mediator between the art and its audience – a cultural shaman of sorts. Despite their specialism in analysing, interpreting and evaluating art, the critic stands apart from the traditional art historian in that specific training is not a requirement for the position, therefore permitting a freedom from institutional ties. The critic can assume the role of a tastemaker in their analysis and interpretation of new work and provide either its support or dismissal; both Roger Fry and Clement Greenberg championed artists who were mocked at the time. For Greenberg a good critic excels through “insights into the evidence … and by … loyalty to the relevant”; T.S. Eliot, writing on criticism suggested, “a critic must have a very highly developed sense of fact.” In 1971, Harold C. Schonberg, chief music critic of The New York Times for over 20 years and the first music critic to receive the Pulitzer Prize for criticism, said that he wrote for himself, ”not necessarily for readers, not for musicians. …It’s not a critic’s job to be right or wrong; it’s his job to express an opinion in readable English.” For the critic expressing opinions are as important as disseminating facts.

”90% of all art is bad. What makes it interesting is that YOUR 90% and MY 90% are different.” – Jerry Saltz

Much of Vaughan’s ire was directed towards the machinations of the general art world in which his permissible dislike of Feldman’s paintings got tangled. Saltz response was defensive: “Should I even suggest that to like this review reveals some sort of deep bitterness or resentment? Not to anyone here. But that is what snark and cynicism do together: They collude, form a club of mutual self-congratulation for calling other people names and saying THOSE people are not pure like we are. A critic has to self-examine WHAT he/she does not like about the work and STATE and PROVE that.” Further suggesting ”90% of all art is bad. What makes it interesting is that YOUR 90% and MY 90% are different. Each of us tries to make a case FOR the work we like. We do NOT resort to snarkily saying the art we don’t like “is about money.” But, is it useful to criticize Vaughan for disliking Feldman’s work based on how it fits into the overall art world and market?

“fucking dreadful,” – Brian Sewell comments on Damien Hirst

Of course, harsh reviews and equally severe responses are in no way a new phenomenon and have been around long before John Ruskin accused Whistler of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” The late Brian Sewell, one of the UK’s best loved critics called Damien Hirst “fucking dreadful,” David Hockney “a vulgar prankster,” and once suggested that Banksy “should have been put down at birth.” While Julian Spalding, writer and former museum director, banned by Damien Hirst from the opening of his Tate retrospective in 2012, famously called Yinka Shonibare’s £535,000 Fourth Plinth project a “crassly designed…ocean one-liner floating in a sea of public funding.” However, in a social media world where artists often rely on cult of personality (interestingly harking back to Wincklemann’s critique of Vasari) through their online presence and following, in which a façade of shallow popularity is maintained, where names are recognized before ideas, could the critic’s snark provide a counter-balance to this online world where only ‘likes’ are allowed’? Representing an opposite to these positive actions, the critic’s role is in part to identify contextual weaknesses.

To conclude, I am reminded of the saccharine-soaked palette of Joe Wright’s episode of Black Mirror where everyone’s personal interactions are rated; a world where fake smiles and politeness pervade due to fear of ostracization rather than genuine engagement. Everyone is a critic and everyone is open to criticism. Without advocating Pyrrhonism, is a teensy-weensy bit of snark a relief from this politeness?

What's Your Reaction?

Writer, Cultbytes Curator and writer based in Berlin. Having worked for 6 years at The Douglas Hyde Gallery in Dublin, she moved to Sweden in 2011 to undertake an MA in curating contemporary art at Stockholm University. In 2015, she formed part of CuratorLab at Konstfack Stockholm where she investigated the folklore and local history of her hometown in Kildare, Ireland. She is also initiator and curator of Couchsurfers Paradise, a series of exhibitions unfolding in the homes of strangers. Additional recent projects have included Ritual Play, Verkstad Konsthall, Norrköping, and Faraway Longings, Irish Embassy Berlin. During the 2017 exhibition season, she will act as director of Dada Post, a project space in Berlin. l i-gram l