William Kentridge is a Star Among Many at Powerhouse Arts’ Artists Celebration

“We want you to return vigorously,” Eric Shiner, president of Powerhouse Arts, said in his welcome address to some 700 guests in the building’s Great Hall, where a stage has been built for the performance festival Powerhouse: International. I love it, I mouthed to my guest. Many well-funded large-scale institutions are cathedral-like and austere, places where one is quiet and observes—nothing vigorous is welcome, let alone encouraged. Powerhouse Arts, on the other hand, is playful with an open invitation to create within the building and add to its energy.

Thursday marked PHA’s second annual artist celebration, Fête of the Fates, an hour-long journey through the building’s ceramic, metal, print, and textile shops with presentations, demos, and bites on the way. On the second floor, multi-media artist Lauren Cohen, an alumnus of PHA’s Ace Hotel residency, presented ceramics from her Gallerina series. A multi-year performance project where the artist worked as a gallery girl, culminating in a series of ceramic pieces (that represent what it means to work in an art gallery) and a 14-minute film, which will premiere this fall. Cohen’s work was on view in the exhibition Body Grounds, alongside Jacob Olmedo, Stephanie Santana, and Pacifico Silano. Liz Collins spoke about her textile mural Tundra Gardens—the backdrop for our drinks later in The Loft. Everything was created in the building. The food journey format encouraged interesting meetings with materials, letting us non-artists in on what is feels like to make art: intuitive, weird, and fun.

“Your printer is the largest in the U.S., right?,” I asked the head of the print shop excitedly as I shook his hand in the elevator. “I’m not mad at that rumor,” he responded, gesturing an inch or two with his hands. He invited me to come by and see for myself, any time. I like PHA for artists, as fabrication costs seem to be lower than many other places, and they can fabricate at higher volumes in less time than smaller studios. And, artists who work at PHA receive support from skilled technicians eager to help problem-solve. (No, this is not sponsored content—I just like keeping my ear to the ground when it comes to fabrication).

Following the Fête of the Fates journey, we were ushered into the theater for the New York premiere of Sibyl. There, PHA’s founder Joshua Rechnitz, who spearheaded the $180 million building renovation, a poet, if not in practice, at least in heart, delivered a surprisingly evocative speech: “I refer again to this place, to this project, as a ship. We are at the edge of the lapping waters. A conduit to the sea. I want to voyage on the oceans of the ‘real.’ Away from the ceaseless, near-inescapable barrage of vacuous noise… I want to move at a more human pace. To remove myself to books and to plumb the very real world of capital-A ‘Art’. Don’t we all?” In a climate where most New York artists wish for a lifeboat, Rechnitz built them a ship. And, he teared up as he thanked his wife. King. “This is your crew and one that wants to support you,” I said to Cohen over desserts and more drinks when I ran into her after the performance. It is a good crew to be part of.

When William Kentridge stepped onto the stage to introduce his work, he was wearing a black suit and a loose-fitting crisp white shirt tucked into his pants. His uniform and the way he is depicted in his video work—well, sans jacket. He lamtented the U.S. aid being pulled from public health programs addressing HIV in his native South Africa. Linking both countries, he noted that the U.S. and South African art worlds are largely supported by private donations, rather than public funding. Something that rang clear in a room populated largely by patrons and artists, and their friends. It is always impactful when an artist is allowed to be political; art listens to politics, but politics does not always listen to art—the public should listen to both. Bringing Sibyl, an award-winning and experimental piece by one of our time’s most impactful visual artists to New York audiences reinforces PHA as a fertile creative ground where everything is possible.

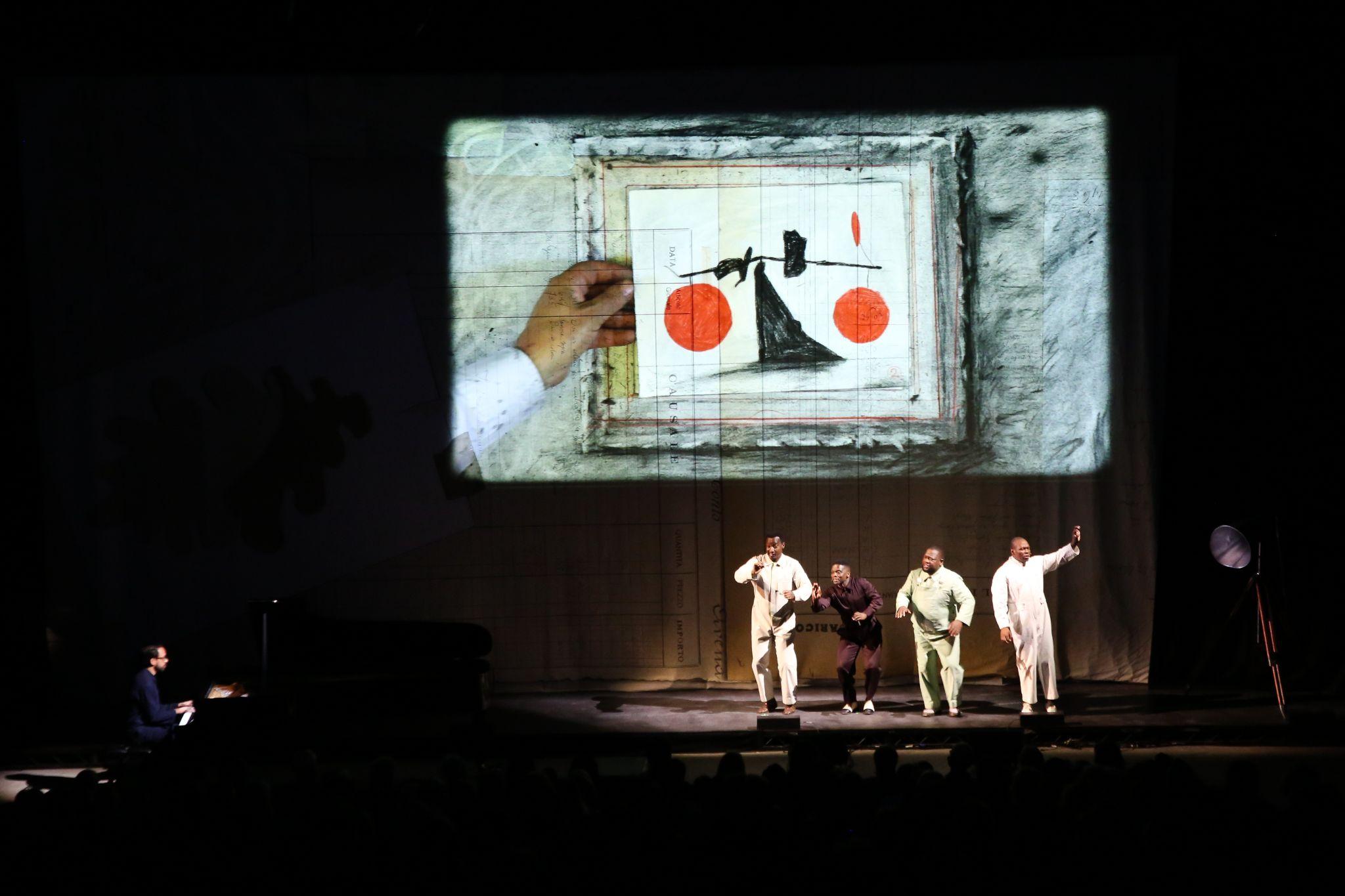

Kentridge’s opera Sibyl is a merger of two pieces. The Moment Has Gone, a film by Kentridge with an original piano score by Kyle Shepherd and an incredible all-male vocal chorus led by Nhlanhla Mahlangu, and Waiting for the Sibyl (2019), a chamber opera featuring ten performers. The first centers on an animated drawing across a large screen depicting the construction and deconstruction of Calder’s rotating mobiles in drawing. It draws inspiration from an opera, Work in Progress by the American artist Alexander Calder that premiered in Rome in 1968. Kentridge shared in his introduction that the balletic cyclists and mobiles in Calder’s version were too costly to incorporate; instead, he opted for the live singing-accompanied video to prelude the opera. The clucking, harmonies, and chanting of the chorus carried the piece.

After an intermission, the opera part began. A screen drops and rises, like a curtain, to reveal a printing press or news bureau, the clicking of typewriters, hammer printing, and a man picking up a paper, like a phone, and as he holds it to his ear, the cacophony of noise that these office types would emit reveals itself. The screen drops and rises again, revealing a new scenography: “RESIST the third Martini,” a page of a book screamed on stage as the performer Sibyl danced, frenzied, throwing her skirts to and fro and above her head, creating a shadow play on the opposite page. Then: something along the lines of “RESIST brushing against her knee.” I’ll take it, I think to myself, and try to figure out what is going on. Kentridge’s visual language is ambitious and complex, populated by recurring objects and textual declarations that represent larger themes (often within South African politics) and memories—his style of morphing, drawing, and erasing charcoal, guided by association, and sometimes his hands present on the screen, is admired by many, but I always fail to get carried away. Sometimes, to even understand. In Ancient Greece, Sibyl wrote prophecies on oak leaves, then left them at the mouth of her cave to disperse haphazardly in the wind. Kentridge’s opera is about fate, future, death, and prophecy—technology plays a big role. I loved the costuming, hats and pleats, and shapes spinning (like Calder mobiles), and when paper was scattered (like Sibyl’s prophecies), and how they remained on the stage as the performers took their bow. The Moment Has Gone and Sibyl are connected through tenuous fragments; I would rather have seen them apart.

The performance festival Powerhouse: International continues through December 13th. After speaking to its founder, David Binder, the former artistic director of BAM and a Tony-award winning producer, I marked Good Sex in my calendar. It is a piece by Irish company Dead Centre, bringing two people we know of, but who do not necessarily know each other, and an intimacy director together to discuss (and perform?) sex on stage. Hilarious. Two new people will take the stage for four nights—names to be released shortly. Good Sex will mark my vigorous return to Powerhouse Arts. Pun intended.

Snaps From the Party

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.