An Intimate Sense of Dislocation: Warsza’s Roma Pavilion in Venice and an Itinerant Friend

A conversation with Joanna Warsza co-curator of the Polish Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale with the work of Roma artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas on view through Nov 27, 2022, and together with Sina Najafi, co-curator of the exhibition “And Warren Niesłuchowski was there: Guest, Host, Guest” on view at Cabinet 300 Nevins Street, Brooklyn through Nov 6, 2022.

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand: You co-curated the Polish Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale with the work of Roma artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, when did you first meet the artist? What were your first impressions and how have they evolved?

Joanna Warsza: As I am writing those lines, an image of Facebook memory popped up on my screen from a day, exactly 3 years ago in autumn 2019, when I saw Małgorzata Mirga-Tas patchworks and textiles at the art biennale in Timishoara. Only three years ago and ages ago. I was stunned by her work, its multilayers and complexity but also felt regretful of the fact that as curator from Poland I didn’t know the work of such an artist stemming from one of the country minorities. And, I was not alone, when we won the competition for the Venice Biennale pavilion, in the autumn of 2021, half of the professionals in Poland did not know her yet.

AME: The Romani people live across Europe, including in Poland. However, this is the first time in the 127-year history of Venice Bienniale that a Romani artist represents a European state. Mirga-Tas was selected by the Polish National Art Gallery to represent Poland. Who was on this committee? How did you get involved?

JW: Małgorzata is the first-time a Roma artist represents a national state. The Roma community is the biggest minority in Europe, counting 12 million people, however to this day they remain largely at the margins of the European society. The pavilion was not only Polish, but also Roma and above all transnational. And how did it happen? In Poland since over 20 years every professional can apply to curate the pavilion in Venice, and the whole process is democratic and transparent, it is perhaps a remnant from the past. Together with the co-curator Wojciech Szymański we won the competition. The jury was big, around 20 people, half of whom were from the central-left wing and half of them right wing spectrum. In some sense, Małgorzata’s work became conciliatory since both sides saw something in it.

AME: Feminist author Silvia Federici’s book “Re-Enchanting the World” gives title to the Polish Pavilion. And, earlier this year, in March, at CuratorLab in Stockholm you organized the conversation “Let the women end the war” between Lizaveta German, co-curator of the Ukrainian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale and the exiled artist Maria Kulikovska.“If women ruled the world this would not have happened,” said German referencing the devastating escalation of the war while Kulikovska questioned conscription for only men, highlighted that it forces people into roles based on gender rather than ability. This conversation was a collegial act that reinforced a desire to work towards gender equity, or female empowerment, even in distress. Beyond the context of the Biennale, how do you situate your work within feminist practices, female empowerment, and centring woman makers in your practice and why is it important?

JW: I recently realized that my knowledge of art history when it comes to old white men has many blind spots. This is because I have studied art via gender studies, etudes feminine, and performance with Beatrice (today Paul) Preciado. In some sense feminism is the founding discipline on which I have built interest in other fields – be it contemporary art, theater and dance or theory. A feminist-centric view, among other things, helps to decenter various relations of power that we fall into, it also makes a world less violent place. I try to support feminist people. Warren Niesłuchowski was definitely one of them. The conversation you mentioned, organized at CuratorLab, was just driven by a simple reflection then one of the devastating consequences of the Russian aggression in Ukraine was a sudden lack of women, in politics, in decision-making, at large. Instead of listening to another male combative voice I wanted to hear women art practitioners and young mothers at this terrible distressful moment. The same voice was privileged at the pavilion, together with Wojciech Szymański, we felt bitterly lucky that despite the current political climate in Eastern Europe, we were able to present Małgorzata’s work. Her work is anti-imperialistic, anti-xenophobic, and multidirectional, and as she says – my feminism doesn’t shout, it tells stories. So I believe feminism is a way of making us more soft, tender and interdependent, thinking about how we can relate not only to each other but also to mountains, plants or rivers.

AME: In the colorful patchwork wall hangings, the artist has followed the visual lexicon of Palazzo Schifanoia, including zodiac signs, the decan system, allegories of months, cyclicity and the migration of images across time and place – India, Persia, Asia Minor, ancient Greece, Egypt and Europe – it engages with migratory patterns. However, she has also incorporated Polish-Romani symbology. What new, if any, ideology does this create?

JW: Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara is where the art historian Aby Warburg developed his famous concept of iconology, seeing images as travelling vehicles, as having Nachleben, a “life after life”. According to Warburg, an image is not something fixed, assigned to one culture or place. He reconstructed the long journey of some of the motifs appearing in Ferrara through space and time. As one might expect, his analysis lacked any mention of Romani culture, even though the Roma, who migrated from India to Europe, played a very important role in this transport of meanings. We were inspired by Palazzo Schifanoia and its structure of meaning to re-activate the mechanism of the wandering of images and to revive symbols important to the artist and to Roma culture. Reaching for this very important reference in the art history is an attempt to add, to complement, to weave and to repair (in a literal sense, because seemingly incompatible elements and second-hand clothes are put together) threads of Roma culture into art history and into contemporary transnational art.

AME: Mirga-Tas work is also on view at the 11th Berlin Biennial and in Kassel at Documenta 15. What are your hopes for the artist and your relationship?

JW: Our Venice pavilion will have an afterlife. It will first go to Ferrara and then other places. We have many plans, but you know how it is, there needs to be good circumstances, will, context and sometimes some chance for something beautiful and unexpected to happen.

AME: Even though much of your research has been focused on public art, your curatorial work has been embedded within intimacy for quite some time. The book and exhibition ”And Warren Niesłuchowski was there: Guest, Host, Guest” examines art world figure Warren Niesłuchowski’s (1946–2019) correspondence during his transient years when he did not have a permanent home. While ”Die Balkone,” a public art project that you initiated during the pandemic, invited artists to present work in balconies and windows, bringing the domestic space to the public. Do you relate to the term intimacy and how, or why not?

Art is usually an expression and sublimation of something very personal, and yet when it sees the light it is rare that its early intimacy is being shared and experienced by others. The question is how this intimacy, be emotional, cognitive or spiritual, can be passed over with the language of art. Can you use the medium of an exhibition, en sense large, to nurture the idea of feeling close. “Die Balkone,” co-curated with Övül Ö. Durmusoglu, was an invitation to the artists, at the time of the pandemic, to exhibit in windows and balconies. Under the lockdown the artists displayed their inner state of being, they sent smoke signals to each other when everyone was confined at home. The windows became membranes, the thresholds between the in and out, between the private and the public, and art a language of overcoming isolation and fear.

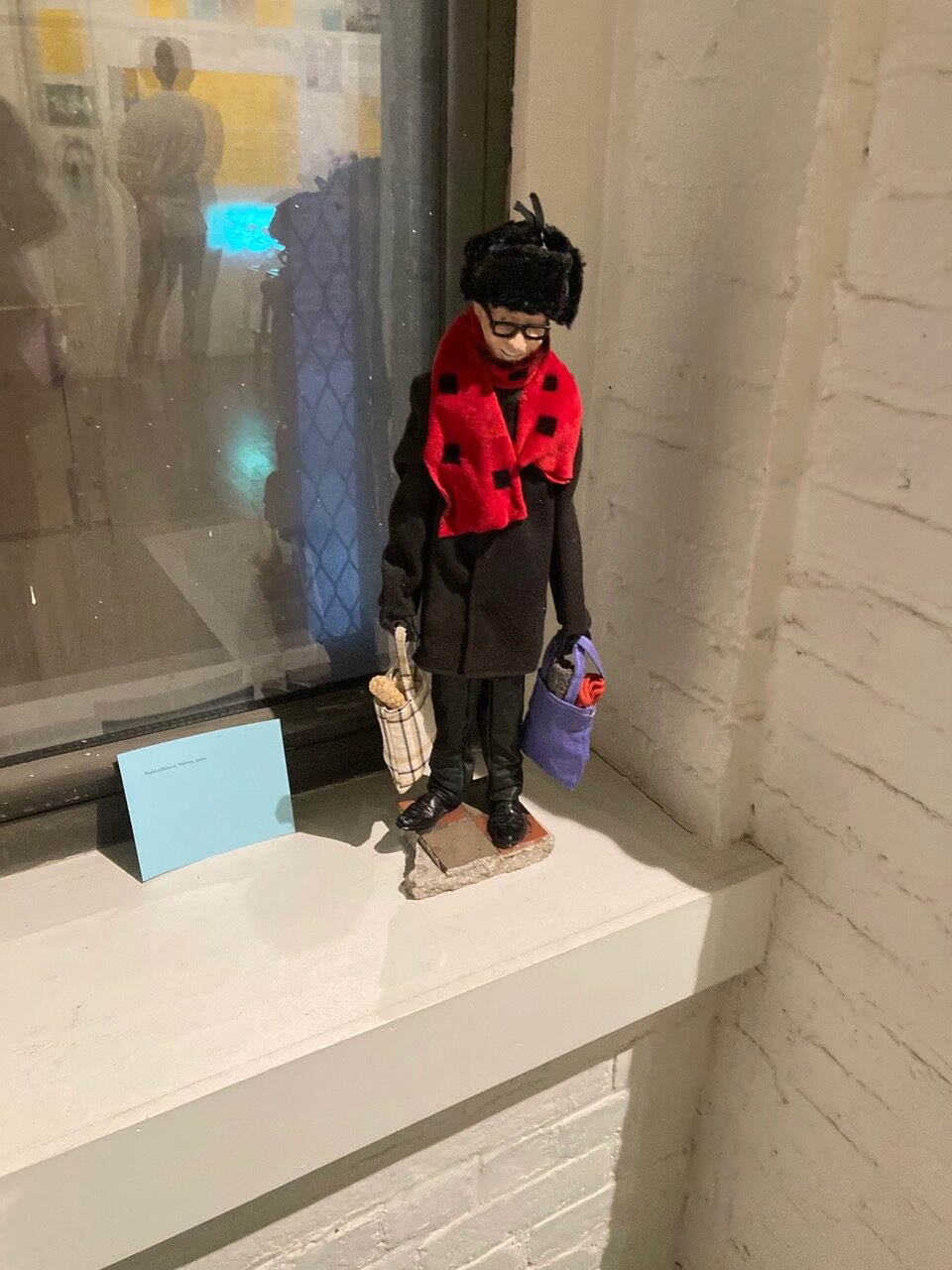

The traveling exhibition which is now in New York “And Warren Niesłuchowski was there: Guest, Host, Guest,” co-curated with Sina Najafi grew out of our friendship and awe for our late friend who dared to inhabit the periphery of social norms. Niesłuchowski, who at the age of 59 decided to be homeless in the art world and live as a guest of others coming and going on his own unpredictable schedule was above all an amazing companion. He was many things at once: a walking bibliography, an exhilarating conversationalist, a polymath, a dandy who cultivated various forms of friendship and camaraderie. Since he refused to produce anything the backbone of this exhibition is the only thing he left behind, which is his words and the e-mail correspondence with many of his hosts. We also show some of the the artworks he inspired. Niesłuchowski was capable to built relations with almost anyone, since he was a profound listener, he made people seen and heard. He showed that intimacy is not only romantic or sexual, that it is also a relationship where power can be suspended or altered, and that generosity is a stout force.

AME: With Poland playing a large part in welcoming Ukrainian refugees and raising awareness about the war in different spheres, your exhibition about Niesłuchowski is timely. He was born in to Polish parents in a refugee camp in Germany following the second world war. What methodologies did you use to chart his ideas about war, migration, and belonging? Which of his ideas seems prescient now?

JW: Niesłuchowski inherited his fundamental sense of dislocation, being a son of forced labor workers and growing up in a displaced people camp. The family waited over five years to be able to emigrate to the United States. He must have been informed by those years of longing for a home yet to come, and as he was himself saying in a beautiful film portrait by Simon Leung: “I am looking for an adoption by imaginary family.” We were interested in the radicality of the gesture of not having a home of your own if you can have one, in the resilience of the decision to go on the road in the artworld. He did it not to have a job, next gig, nor gain an invitation, but simply to accompany others, to live as networker without status, as an itinerant conversationalist. The title of the exhibition is a sentence from “I Love Dick,” the novel by Chris Kraus where Niesłuchowski is a periphery character. And, that was the nature of his migration, being in the second plane and yet visible to others and depending on their hospitality.

It should be said that his was not, other than at beginning of his life, a forced migration under the inhuman circumstances that many people on the planet are experiencing today. Niesłuchowski had the privilege of deciding to be “out of place,” to avoid any defined role, and to inhabit the periphery of social norms. We present a life of strategic exile and ontological homelessness in which he felt at home everywhere, and nowhere. The fact that he decided again to go “into circulation” as Barry Schabsky writes, shows that the condition of war and displacement never really leaves you, and although it is extremely distressful – for Niesłuchowski it offered a life outside of the capitalist norm, outside the unconditional purposefulness or efficiency.

Warsza is also the program director of CuratorLab at Konstfack University of Arts, an editor and writer. The most recent book published under her leadership is Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art in the 1980s and 1990s.

You Might Also Like

An Important Role Model: Allison Glenn, Associate Curator at Crystal Bridges

The Immigrant Artist Biennial Offers a Lesson in Perseverance

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.