Body Spirit Geology: Women Artists Working with Metaphysical Presence

In a life-changing instant—the sudden death of her husband—Japanese artist Hanae Utamura went from creating artwork that spoke to geopolitical collective memory in Japan, to exploring the realm of the personal through the body and the metaphysical. Her prior series of projects looked outward to the world and spoke to collective pain, suffering, death, loss, and trauma. Her newer work looks inward to our spiritual being, birth, grief, and the biological earthly entities that create us. Despite this challenge, Utamura is light-hearted and thoughtful. We met while welcoming El Salvadoran artist Beatriz Cortez’s time-based visual art project, Ilopango: The Volcano that Left: a Calder-stabile-like metal sculpture to Troy. In the shape of a volcano—a symbol in both Salvadoran culture and in Mesoamerican codices—it brings ideas of the Mayan underworld to the fore. In Troy, we participated in a ceremony to bless the Native American burial site with tobacco while Ilopango passed by us on the river.

Unbeknownst to Utamura’s recent loss, I was drawn to her bubbly and friendly nature and intrigued by her knowledge of indigenous practices. Perhaps it was our proximity to other realms that connected us—my mother lost her mother at a young age and has explored modes of communication with spirits, exposing me to conversation and practice surrounding energetic transitions. In recent years, spiritual art by women tracing back to modernist and proto-modernist abstraction is more widely known, facts that Jennifer Higgies writes about in her new survey The Other Side: A History of Women in Art and the Spirit World. As we offered tobacco to the land, Utamura invited me to visit her studio on the Rensselaer PoIytechnic Institute’s (RPI) nearby campus, where she is enrolled in a practice PhD program, and I accepted.

At her studio, Utamura told an unexpected and moving story about the recent transition in her artwork style. Her husband, Robert Phillips, was an American new music composer. They were an artistic couple who met in 2014 at Akademie Schloss Solitude, an international artist residency in Stuttgart, Germany. Within a very short period after the world entered the pandemic, Utamura experienced bringing life into the world, giving birth to their son, Kai, in 2021. Shortly thereafter, in 2023, she saw life leave the world with Robert’s death due to sudden illness. It was a devastating and unexpected tragedy for the young couple and their family.

On the 49th day after Robert’s passing, which in Buddhist tradition marks the day when one’s spirit and energy are fully released, Utamura performed a ritual to honor him. She had saved the placenta from Kai’s birth (which is dried in the shape of a bowl), placed Robert’s hair inside the placenta, and buried both together beneath a tree. When Utamura and Robert spent their last moments with each other, they exchanged locks of hair. The placenta provides oxygen and nutrients to the child through the umbilical cord, which also brings waste products away. It is shaped like a brain, or as Utamura describes it, a “half-cut earth,” and symbolizes growth and birth. “Placenta is treated as medical waste after birth in the Western medical world, but many cultures have a sacred, spiritual relationship to the placenta,” she commented. The placenta is often referred to as the “tree of life” for the branch-like patterns made by its blood vessels. The site continues Robert and Utamura’s life together, as the placenta’s nutrients—parts of their DNA—enrich the grass and tree roots, and other, in her words, “non-human species.” And, Utamura’s ritual symbolized Kai protecting Robert’s spirit, and carrying him into spiritual transcendence, with the eternal protection of his son.

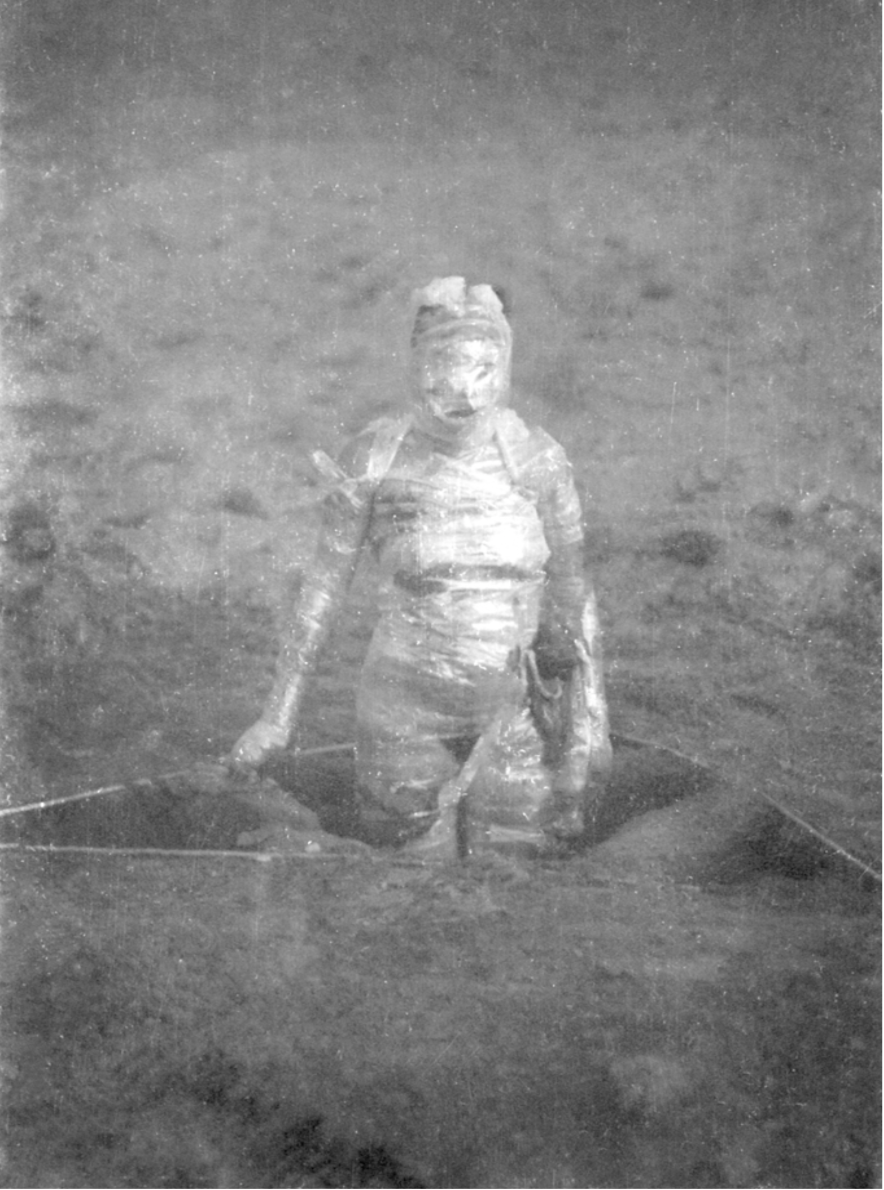

Pioneering feminist artists from the early eighties also worked with the idea of the placenta as considered “medical waste” in Western medicine, while it is spiritual, such as Colombian artist Maria Evelia Marmolejo (who was included in the 2017-2018 exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art 1960-1985 Hammer Museum and Brooklyn Museum). For Marmolejo’s 1982 performance, Anónimo 4, she dug a 1.5-meter triangular pit into the ground and filled it with sewer water and the placentas of all the babies born that day in hospitals near the performance site, in Cali, Colombia and Guayaquil, Ecuador. She wrapped her body in the placentas, and submerged herself in the hole, “embarking on a psychological and sociological self-exploration of the fear of being born in a society in which there is no guarantee of survival,” she explains in an interview. Artists like Marmolejo and Utamura observe the importance of the placenta by incorporating them into their performance rituals in meaningful, powerful, spiritual, and symbolic ways, whereas at the hospitals, they tend to be discarded.

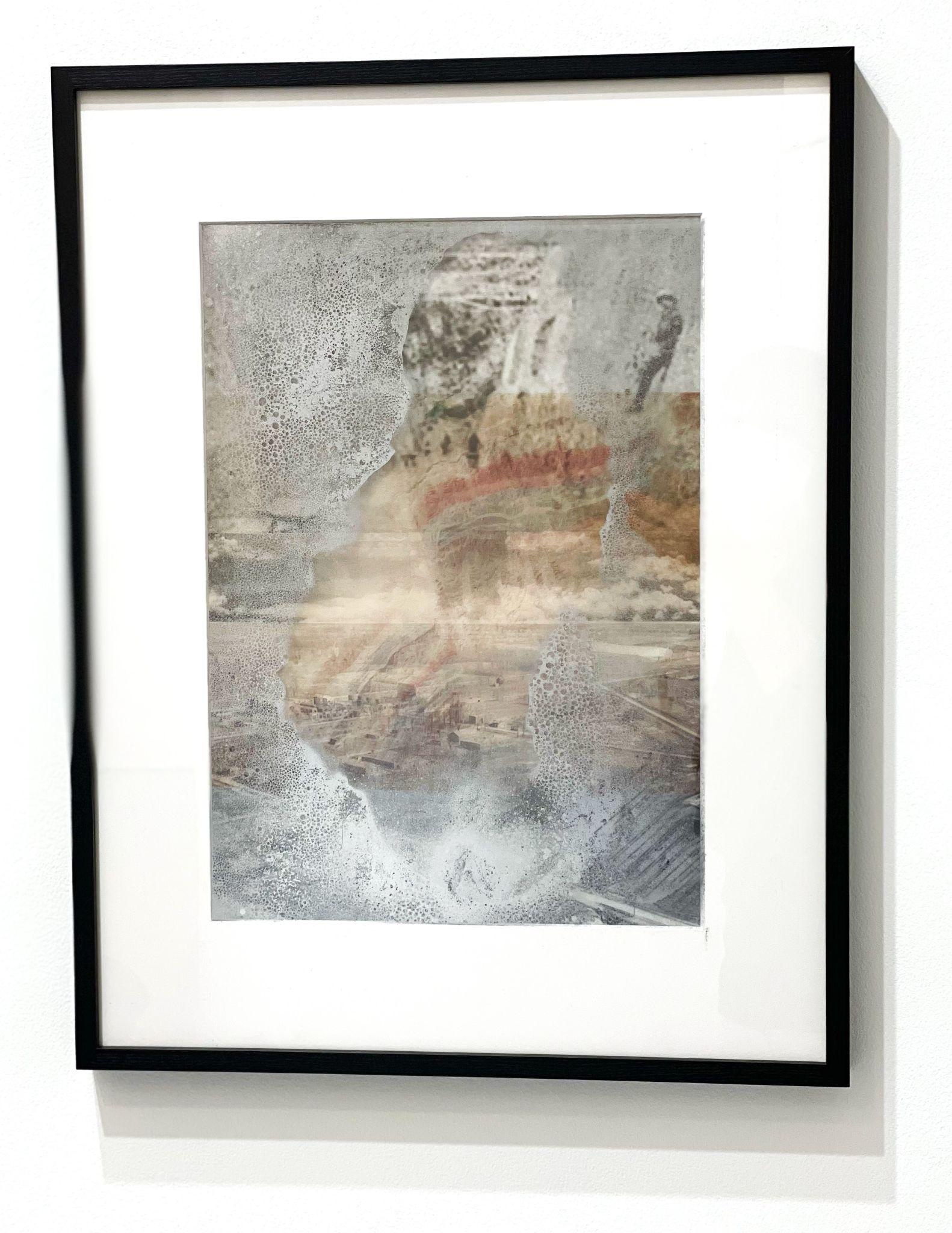

Understandably, Utamura could not entirely let go of her partner. Because of these sudden extreme encounters with life and death, which now flow, in her words, “like the confluence of the river with raising Kai,” her perspective was instantaneously transformed, altering her artistic practice. Before Robert’s death, she created more geo-political artworks, often performances and films. One work Uncanny Valley – Study for Future Strata (see image below) raises questions around the dominant historical narrative of nuclear history by juxtaposing images of the elements that surrounded the atomic mushroom clouds of the bombing in Nagasaki, with the mining site in Congo where uranium was sourced for nuclear production – positioned above, and the military storage site near Niagara Falls where nuclear waste from the Manhattan Project was secretly disposed – positioned below. But, after she experienced the life-altering sequence of birth and death events, she felt compelled to turn inward to the body and spirit. Abstract painting helped her overcome “the unspeakable”—I immediately drew a parallel to the shift to abstraction in Western art after World War II. She believes in abstract painting as a powerful medium for channeling the energetic transitions relating to birth and death.

“This has also very much been a collaborative process with Robert,” Utamura added, “Aur means ‘light’ in Hebrew. I feel that his symbolic composition, Aur, for string quartet and electronics, is the light that he transcended into. It transforms death into a departure. When painting, I hear his music inside my ear—his essence is expressed even more through his music in his physical absence. The music truly starts to live in eternity within me.” Having followed my mother’s journey to stay in touch with my grandmother after her death Utamura’s will to stay connected as a source of comfort resonated with my own experiences.

The first several paintings Utamura created exploring her feelings of grief were watery representations of a body, dissolving. After creating several of these more figurative paintings, she was invited to a séance by Tamar Gordon, a professor of Anthropology in the Communication and Media department at RPI, and a member of her doctoral committee. The séance would help her further shift her focus from grief to communication.

At the séance, the physical medium Gary Mannion, headed a circle under controlled conditions, alternating between complete darkness and red light. Physical mediums, as opposed to mental mediums, produce materializations of spirits while mental mediums interpret and channel them. Physical mediums produce ectoplasms which are viscous manifestations of spirits that exude from their body taking on any form, including apparitions. Encircled by the participants and sitting in a cabinet, tied down to a chair, Mannion produced an ectoplasmic hand and invited members to touch and hold it. Utamura described the experience as having felt like “touching a wet hand.”

Séances were an American phenomenon popularized by the Spiritualist movement in the 1850s. They spread to Britain, other parts of Europe, Brazil, and Australia, and consisted of circles of sitters who gathered to channel the realm of spirits. Today, they are less common, but exist and Mannion is a leading figure in the field.

Utamura’s new work is also influenced by Shannon Taggart, a photographer and artist who authored a popular book depicting sitters in various states of transfiguration. Taggart recently had an exhibition of her work at the Opalka Gallery in Albany, NY. The two-day public opening included a dialogue between Taggart and Dr. Anne D. Braude, the director of Women’s Studies in Religion at Harvard Divinity School, and the author of the book, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-century America, which explores the close engagement of Spiritualism with the women’s rights movement. There is also a growing recognition in recent years of female artists like Hilma af Klint and Agnes Pelton, who employed art as a language to explore spirituality. Utamura considers her work as in alignment with these artists and thinkers.

After the séance with Mannion, Utamura created another series of paintings in which she began to depict the imaginary body that evolves to a more abstract state in its process, like energies and colors (rather than a dissolving figure), with rich, cosmic dark blues or brighter florals. Often she incorporates a bit of iridescent pigment “inspiring to channel, as it reflects light” she explains. The composition of Utamura’s new more abstract paintings on paper are vaginal and womb- or placenta-like. Some of these images incorporate a hand and a tree branch, perhaps referencing the tree under which she performed the ritual for Robert, or the sensation of touching a wet hand in the séance.

Serendipitously, a few months before Robert’s passing, she also found a book lying in a classroom at RPI titled The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult published by Yale University Press. It is the catalog from an exhibition in 2005 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that showcased the history of photography on mediumship channeling with the spiritual realm, with imagery dating back to the nineteenth century. There is a page in the book that shows photography which captured ectoplasmic emissions, and the composition of these images have similarities to the composition of Utamura’s new paintings. She has a feeling that her spiritual involvement with the other realm was and is still being presented to her from many different angles.

Both of these newer series explore what comes before, what happens during, and what comes after, an extreme moment—global or personal. “We are living through dark times with a lot of death,” Utamura remarked sensitively in her studio, putting aside her personal loss and experience, knowing that this is going on all around us. “We’ve learned to accumulate, but we are not taught much about how to face loss. I think it is time for us to face this; exploring these spaces would also bring us more understanding of life in its complexity, and knowledge of how to nourish life. It will prepare us with strong grounds for the future to come. The more darkness that falls upon us, we also need light that illuminates our world.”

In Memory of Robert Phillips.

You Might Also Like

A Workshop on Love and Afropresentism with Neema Githere

Larry Ossei-Mensah Curates Show in London on the Afterlife of Empires

Emojis, Memes and Popular Lexicons: KUNSTRAUM’s Newest Exhibition Explores Modes of Communication

What's Your Reaction?

Alexandra Goldman is a writer, curator, and art dealer living in New York. She is Founder of the art publishing platform Artifactoid, and Managing Director of Barro New York, a contemporary art gallery with locations in New York and Buenos Aires. Goldman writes for Artifactoid, Whitehot Magazine, Cultbytes, ArteFuse, Vice-Versa, and Revista Jennifer. She received her M.A. in Art History from Hunter College and received her bachelor’s degree from NYU in Media, Culture, and Communications.