Beatriz Cortez Visualized the Mayan Underworld and Traveled It Up the Hudson River

“Mayans believed that volcanic ash came up from their sacred underworld,” Beatriz Cortez tells a small group under a smaller number of umbrellas huddled waterside in Waterford where the Hudson River meets the Erie Canal. We catch Cortez on the morning of October 30 as she is directing the disassembling of her sculpture “Ilopango, the Volcano that Left” on its way to the Curtis R. Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) where it will be on view in their main concert hall in the group show “Shifting Center.” What started as a static sculpture that Cortez ideated and fabricated in response to the COVID-19 pandemic during a residency at Atelier Calder in France became an experiment in a sculpture performing migration and interinstitutional organizing when the opportunity to show it at a second venue, Storm King, arose. She continues, “The particles of the Mayan underworld then migrated around the world,” she continues explaining that Ilopango volcanic ash has been found in Greenland.

Cortez first came across Tierra Blanca Joven, or the eruption of Ilopango in The Florentine Codex—a 16th-century ethnographic research study of Mesoamerica by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún—as she was trying to make sense of the COVID-19 pandemic by researching other disasters that had wreaked havoc on the globe. Being from El Salvador, she knew Lake Ilopango well but not much about the eruption that blasted the volcano into pieces and later collapsed thus forming the crater. Ilopango erupted in the sixth century C.E. at the height of Mayan civilization, devastating it. It killed tens of thousands of people and its ash covered the ground in a large surrounding area making agriculture impossible the ash that hung in the sky blocked the sun and lowered the Earth’s temperature.

“Multiple temporalities are at play in Ilopango—it relates strongly to ecology but also contemporary migration, the experience of being an immigrant. There were no images of the volcano, so I had to imagine it,” Cortez explains holding a mini-lecture for Alexandra Goldman, director of Barro Gallery, Hanae Utamura, a practice-based Ph.D. candidate at RPI’s art department, and myself. Cortez is currently a professor at U.C. Davis and, as described to Cultbytes by Katya Grokhovsky, one of her current colleagues and the Founding Artistic Director of The Immigrant Artist Biennial and Fall 2023 Visiting Artist in Residence in The Manetti Shrem California Studio at U.C. Davis, as “an incredible artist who makes future-forward—for most unthinkable—large-scale projects.” In Waterford, during our huddle with Cortez, Goldman shares that she has researched The Florentine Codex while Utamura’s work relates to material lifecycles and the ecological impacts of historical events and presence and absence in their visual records. In one work she has removed the mushroom cloud in an image of the nuclear bomb dropping on Hiroshima, only other clouds remain. The excitement is palpable. A leitmotif in the ethos of this traveling sculpture and the people it meets is interconnectedness.

A day earlier, a larger group, including EMPAC’s curatorial team, met at The Sanctuary For Independent Media—a social and climate justice space co-founded by professors from RPI’s Art Department which, in addition to a radio station and TV channel, is the home of an eco-art park, a science project that investigates the toxicity in the surrounding water, a vegetable garden, and a community space for relaxation and healing. Its headquarters are in a disused church that the founders were given on the premise that they would cover the property’s taxes. The Sanctuary located in an underprivileged area of Troy differs largely from the glossiness of EMPAC which constitutes an impressive state-of-the-art performing arts center on RPI’s campus, with four venues created to accommodate acoustic rigor it is an architectural feat designed by Grimshaw with a price tag of $141 million. Utilizing the architecture and audio capacities of EMPAC, the group show “Shifting Center” “proposes alternate techniques and practices to locate and listen to contemporary artworks that are themselves locating and listening to past events in the ever-changing present”—which includes reimagining indigenous instruments and natural phenomenon, as is the case with Cortez.

The Sanctuary’s co-founder Branda Miller explains that they have attempted to create a space “outside of the military complex” to which RPI, as a leading school for engineering and research, is embedded in. Miller and her colleague Kathy High are both artists and professors at Rensselaer and co-hosted the sculpture’s arrival in Troy. Listening to them it is clear that negotiating capital, (de)colonization, and ecology with RPI has created a fraught but not impossible relationship between the institution and its art department. These entanglements are mostly impossible to operate beyond and The Sanctuary navigates these sticky topics with candor.

Indeed, there are many partners involved in realizing the exhibition and performative travel of Cortez’s steel volcano, other organizations include the Vera List Center and Parsons—its journey on the historic fireboat John J. Harvey from Storm King to Troy was live-streamed and a film crew is following it intending to create a documentary film. ”The geography of the institutions created connections with the Hudson River that suited the performative journey of Ilopango and drew out its connections to migration. The journey also positioned the sculpture as a performer with a presence that exists not only in space but in time, showing Ilopango to be temporal as well as material,” curator Vic Brooks explained to Cultbytes. Together with The Sanctuary, the audience was invited to witness the piece passing through the Federal Lock and Dam, along sites of economic, spiritual, and historic importance.

The Hudson River was called The River that Flows Both Ways by the Muh-he ka-ne-ok, also known as the Mohican tribe, who inhabited the area before the arrival of the Europeans. Salt and freshwater meet from the Hudson River and the Eastern Erie Canal. As industries grew in Troy in the nineteenth century and the city emerged as an industrial capital thanks to its waterways which served as transport routes, the Mohicans were displaced. Some decided to shed their indigenous identity and willingly joined re-education programs, but were not accepted in U.S. society afterward. No Mohicans remain in the area today, instead, they have a reservation in Wisconsin. In 2017, The Sanctuary invited members of the Mohican tribe to Troy where tribal members shared knowledge passed down to them about the area, educating the community about the local burial sites.

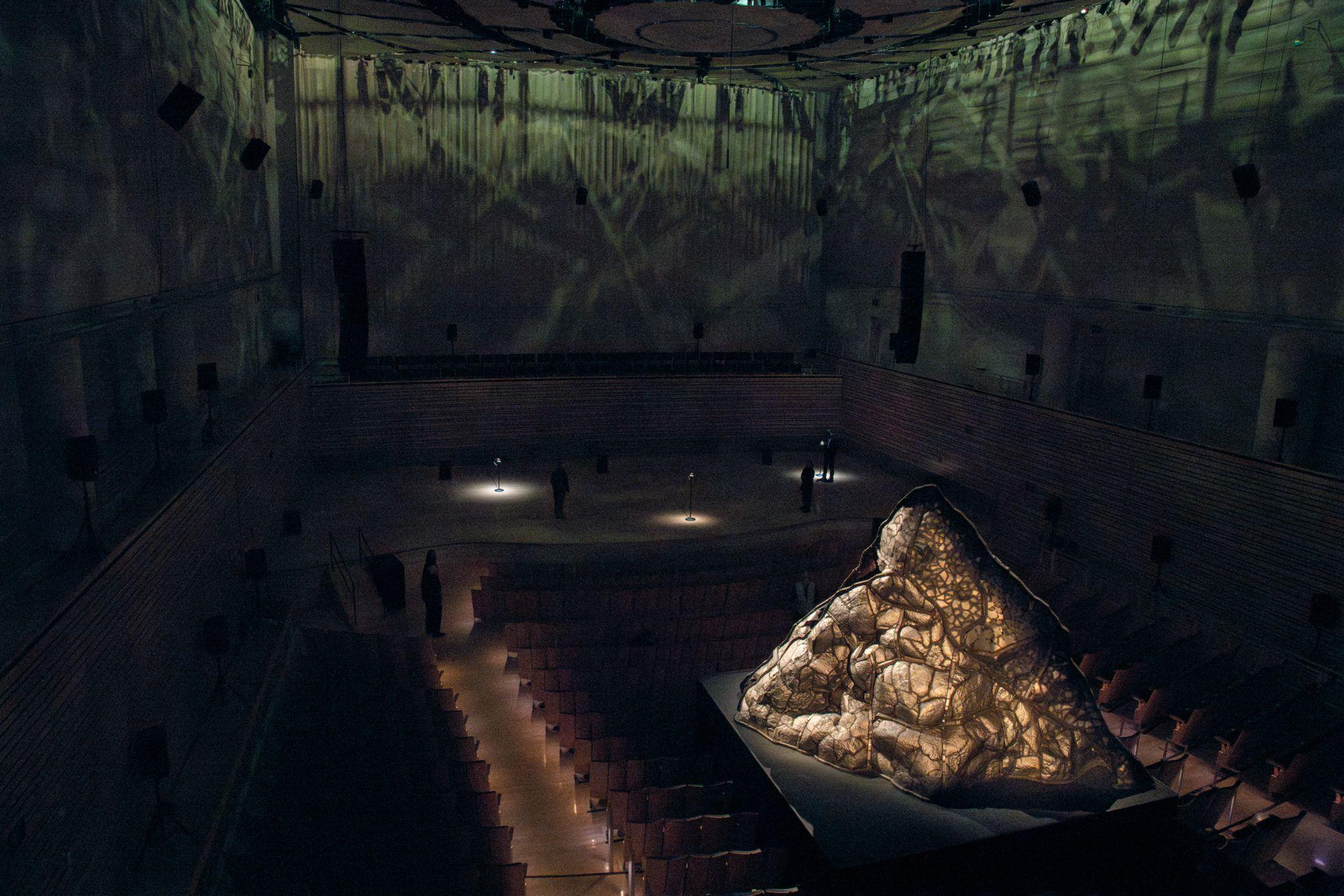

Seeing the gray steel collaged pointy metal sculpture—it consists of hand-hammered steel panels, welded but also screwed together on a skeletal frame—on the white and red fireboat was like the stuff of children’s books. “Wild,” commented Goldman as the fireboat passed us. After we watched, clapped, and cheered as the volcano passed through the Federal Lock and Dam—walking distance from The Sanctuary—we hurried to another site, one of the Mohican sacred burial sites, where we offered tobacco to the ancestors as we caught a final glimpse of “Ilopango” installed on the rear of John J. Harvey as it continued its journey to Waterford. There it would be disassembled and transported to EMPAC for reassembly and on view in “Shifting Center” through November 18.

Speaking with Cortez the next day, I realized that I had taken part in a project that spanned time, place, and culture, extending into the lives of those around us, and which outcome was not known by the artist at its start. By allowing the sculpture to travel and involving many other parties to make it happen, it touched diverse audiences—an ideal outcome for works that happen in public space, or traverse it. Depending on where the audience meets “Ilopango”, their experience of it varies—dislocated it exists somewhere in between the realm of social practice, performance, and sculpture. Exploring negative space but with a positive connotation, Cortez left the sculpture’s imprint on its initial site on Museum Hill at Storm King. “As an immigrant, you are in many places at once,” Cortez explains to us in Waterford. “In your home country, you are remembered by those you left behind. They know how you would act and react to different situations as they unfold as if you were there. And, you are split between multiple places.” Importantly, not only do immigrants leave marks in the places that they leave, but they also shape the places that they arrive to.

“Ilopango, the Volcano that Left” is on view at EMPAC, 110 8th Street EMPAC Building Troy, NY 12180, through November 18 as part of the group exhibition “Shifting Center.”

You Might Also Like

A Swedish Royal Foundation Presents Work by Yinka Shonibare in Open-Air Sculpture Park

Related Tactics—a Bay-Area Collective—Announced as 2023 Rainin Fellow and Awarded $100K

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.