Art Worldings at Play: “COUNTERPUBLIC” Triennial of Public Art – St. Louis, MO

My mother and I visit Flowers and Weeds, a garden shop on Cherokee Street in St. Louis, MO. We peruse a long table of native plants, as well as vegetable starts and perennials. Fidencio Fifield-Perez’s large cut-paper wall piece, accompanied by a plaque with the fluorescent yellow COUNTERPUBLIC exhibition logo on it, catches my eye. The work is installed on the wall dividing the shop’s front showroom, where expensive crystals and pots are on display. The back houses a showroom of lush tropical houseplants. Fifield-Perez has woven shreds and ribbons of receipts, identification paperwork, and other materials used by young undocumented immigrants (Fifield-Perez is a past DACA recipient) beneath splashes of paint, constructing a topography of white, red, government-issued green and blue certificate papers and map lines. Blending partially into the garden shop, the work immediately draws issues of “nativity” and “(up)rooting” into focus. In the larger context of COUNTERPUBLIC, this work triggers cascades of questions about migration, colonialization, and ongoing waves of re-colonialization (a.k.a. gentrification), self-determination, belonging, and geography that move throughout and across the Cherokee neighborhood and motivate this three-month triennial of public art.

My mother and I visit Flowers and Weeds, a garden shop on Cherokee Street in St. Louis, MO. We peruse a long table of native plants, as well as vegetable starts and perennials. Fidencio Fifield-Perez’s large cut-paper wall piece, accompanied by a plaque with the fluorescent yellow COUNTERPUBLIC exhibition logo on it, catches my eye. The work is installed on the wall dividing the shop’s front showroom, where expensive crystals and pots are on display. The back houses a showroom of lush tropical houseplants. Fifield-Perez has woven shreds and ribbons of receipts, identification paperwork, and other materials used by young undocumented immigrants (Fifield-Perez is a past DACA recipient) beneath splashes of paint, constructing a topography of white, red, government-issued green and blue certificate papers and map lines. Blending partially into the garden shop, the work immediately draws issues of “nativity” and “(up)rooting” into focus. In the larger context of COUNTERPUBLIC, this work triggers cascades of questions about migration, colonialization, and ongoing waves of re-colonialization (a.k.a. gentrification), self-determination, belonging, and geography that move throughout and across the Cherokee neighborhood and motivate this three-month triennial of public art.

Previous: Fidencio Fifield-Perez at Flowers and Weeds. Above: Signage at Treffpunkt. All photographs courtesy of the author if not otherwise stated.

Previous: Fidencio Fifield-Perez at Flowers and Weeds. Above: Signage at Treffpunkt. All photographs courtesy of the author if not otherwise stated.

The concept of “counterpublics” is drawn from political theories of Democracy. Rita Felski, Nancy Fraser, and Mary Ryan are best known for using the term, aiming through a (white) Feminist scope at socio-political relations and hegemonic power structures, their mappings entangled with those performed by Moten and Harney, bell hooks, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, and many others. Felski starts by dismantling Jürgen Habermas’s image of the public sphere as a participatory political theatre staged through “open” discourse, through which everyone deliberates as “social equals” in search of consensus about the “common good.” She explains (in a nutshell) that public spheres are constructed through exclusions and that not everyone is invited, permitted, or able to participate (no kidding). Thus, counterpublics are formed to represent the rights and desires of those excluded from dominant forms and spaces of political deliberation. Counterpublic contingencies may compete with, seek recognition within, deconstruct, or disrupt the political hegemonies of (white supremacist, heteropatriarchal, colonial, imperial, ableist, ageist, etc.) “public orders.” However, the idea and existence of one dominant, central public sphere is often maintained by formulations of counterpublics; counterpublics are theorized and enacted to hold hegemonic political states accountable to currently-excluded groups through publicity and through publicizing needs largely to and within extant dominant public(s); counterpublics bring marginalized sensibilities, views, needs, and demands into centralized view. Through counterpublics, that which has been private and personal is made political.

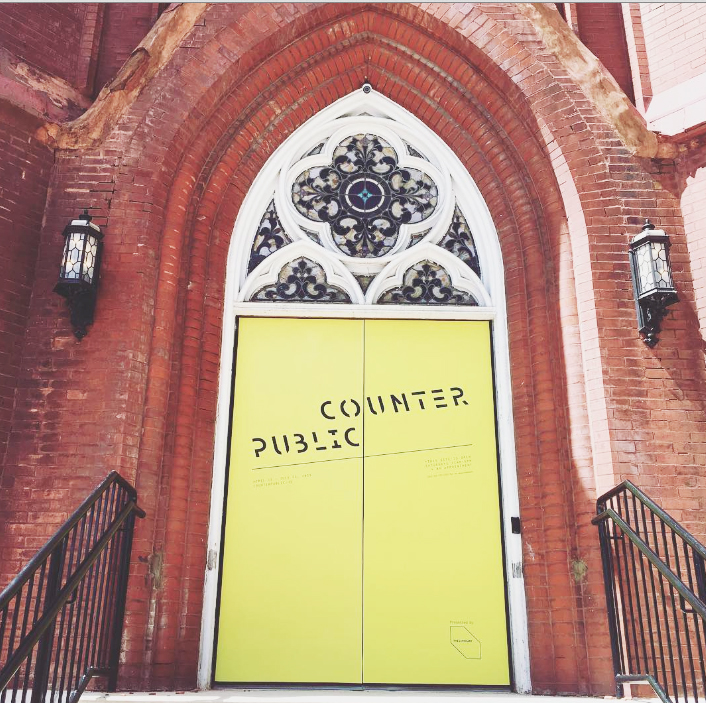

Not surprisingly, then, it seems important to the COUNTERPUBLIC exhibition that the installations, commissions, processions, and events be mediated and publicized as contemporary public art proper. The bright graphic of The Luminary’s COUNTERPUBLIC logo and commissioned street banners both enable navigation through the triennial and visually territorialize the Cherokee neighborhood (Joseph del Pesco’s and Jon Rubin’s signage on a vacant storefront is particularly striking, many other signs and installations are more subtle). The newspaper-style catalog reveals that the 39 artists involved can all be seen (variously and intersectionally) as members of different and convergent counterpublics based on their identities and experiences and also that each is currently engaged in (largely successful) bids for publicity within existing public spheres, e.g. major universities, museums, biennials, and other dominant artworld institutions. For The Luminary, luring the participation of artists poised on the edge of (some fully within the eye of) public artworld prominence requires on-point framing, aesthetics, and theoretical contextualization as well as funding from the NEA, the Andy Warhol Foundation, and other local, regional, and national arts foundations and institutions. Through COUNTERPUBLIC, forms of visibility within “bourgeois public” ways of knowing and seeing are navigated and partially reproduced as demands for representation and recognition within and by them.

Chlöe Bass at Mesa Home. Image courtesy of The Luminary.

Chlöe Bass at Mesa Home. Image courtesy of The Luminary.

Yet, embedded in the artists’ practices and projects themselves, as well as in many elements of the exhibition itself, are nuanced, affective, and structural resistances, recognitions, and considerations. Many of these artists, as well as The Luminary itself (it seems) well understand that assimilation (“inclusion”) and being seen only in the ways already enforced as part of dominant cultural and political orders is often be less desirable than multiplicit, localized construction of “for us, by us” ways of seeing and being. Further, some agency to transform the directions and processes of public discourse may be leveraged by “counterpublic artworldings” which themselves design ways of seeing and recognizing. COUNTERPUBLIC thus operates through conflictual inquiry: how can exhibitions (publicizations) of artistic practice operate otherly-wise within homogenizing clamors for centralization and survival within capitalism, resisting enforced and non-consensual competitions between valuable and non-valuable, visible and invisible? How can a concerned “artificial counterpublic” uproot power dynamics and resist stark binary mappings and restrictive borders?

Kahlil Robert Irving, MOBILE STRUCTURE; RELIEF & Memorial: (Monument Prototype for a Mass), 2019.

Kahlil Robert Irving, MOBILE STRUCTURE; RELIEF & Memorial: (Monument Prototype for a Mass), 2019.

On a rainy Thursday, I follow the newspaper catalog and exhibition logo into shops filled with luxury vintage goods, a performance space where I have not yet attended a show, new event space and bar, and several bakeries. I don’t buy anything and feel a bit like a voyeur or time traveler, trespassing and observing the daily (private) lives of others. I am constantly reminded that I can only write this response from my own body’s location (a white queer cis woman, originally from the Midwest but a transplant to St. Louis after many years in NYC, etc). It matters specifically how and by whom artworldings are performed, and it matters who is watching and to/by whom mattering is made. Further, the ways in which art is produced and exhibited matter, and that these modes of production and distribution must themselves be correlated with the politics and ethics of the work and artists. In a state of pleasurable theoretical agitation, I am moved by interventions such as Theodore (Ted) Kerr’s wheatpasted posters (“If living well is the best revenge then maybe supporting people historically marked for premature death is the best memorial”) and by Kahlil Robert Irving’s MOBILE STRUCTURE; RELIEF & Memorial: (Monument Prototype for a Mass), which seems to capture a piece of the sky and hold it in place, the rectangle of cloud-studded blue (contrasted today against the dark rain) supported by a raw lumber billboard-style frame that rests on a square of gravel.

Azikiwe Mohammed, Amor Photo Studio, 2019.

Azikiwe Mohammed, Amor Photo Studio, 2019.

Many of the artists exhibiting through COUNTERPUBLIC are parsing specific issues of who is seen, who is seeing, and who makes up “the public.” For example, Azikiwe Mohammed operates Amor Photo Studio for a month, providing free portraits for neighborhood residents and making himself available to attend private gatherings, closing out his residency with a set as DJ Black Helmet at Blank Space. Through his work, Mohammad pushes against the white supremacy of mainstream(ing) cultural and political representation, reifying Black imaginaries and substantiating the valuable presences of neighborhood residents.

In many cases, such as through allusions to Mohammad’s ongoing engagement of the imaginary city of New Dovonhame (an amalgamation of the names of the five most densely populated Black cities in the USA), I catch glimpses of ongoing radical practices, encountering installations that themselves memorialize past and ongoing materializations.

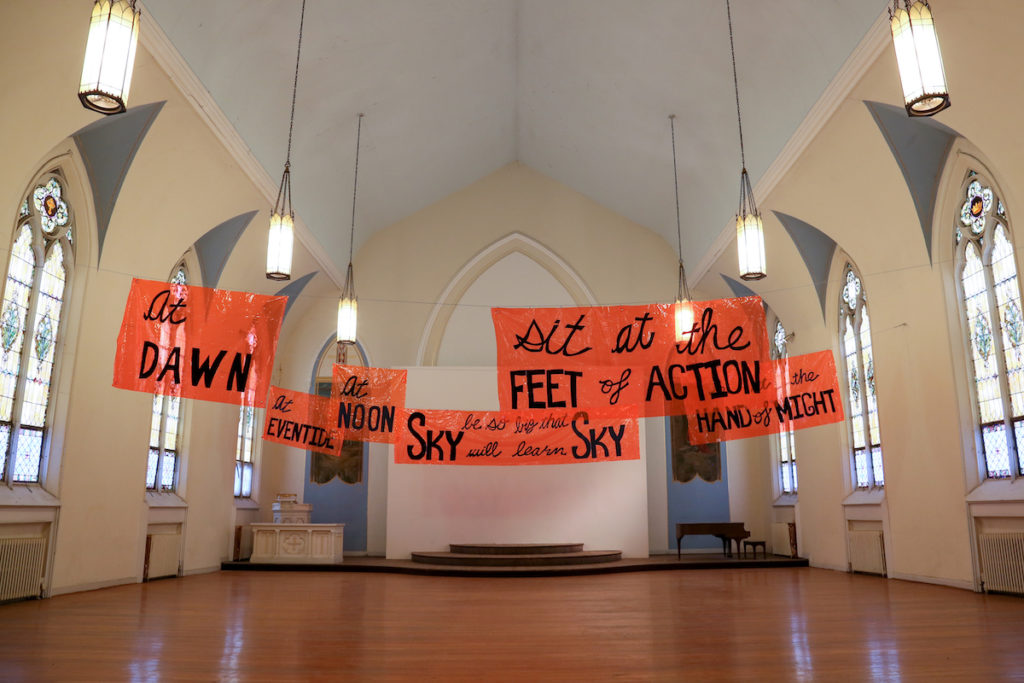

Cauleen Smith, Sky Will Learn Sky, 2019. Installed at Treffpunkt. Image courtesy of The Luminary.

Cauleen Smith, Sky Will Learn Sky, 2019. Installed at Treffpunkt. Image courtesy of The Luminary.

Cauleen Smith’s Sky Will Learn Sky, installed at Treffpunkt, a former church, feels like a spare alter assembled by the last person alive after an apocalypse. Both nostalgic and futurist, the work projects a world in which Black Feminist ideas and ethics are held sacred and directly manifested. Shimmering and quivering above, Smith’s massive banners cite Alice Coltrane: “At dawn, sit at the feet of action. At noon, be at the hand of might. At eventide, be so big that sky will learn sky.” Perhaps this bigness, at eventide, requires a central public platform, a wholeness or holistic arena from which such powerful ideas can be communicated. Yet, counterpublics must also be protected from those who would appropriate, commodify, and assimilate them; structural, ethical, and personal integrities must be simultaneously preserved and positioned.

Lucidly offering up this conflict and its bodily affects, Smith’s work insists that enaction of more life-honoring becomings are possible and urgently asks those who encounter the work to deeply consider how each of us may intentionally design our own public participations and cultural narratives in ways that are neither wholly conditioned and controlled by monumental biocidal systems nor wholly without institutional memory, shared history, and spiritual community. Can we re-form the mainstream monolith, can we create “our own” worlds (the Luminary sells tape measures bearing Buckminster Fuller’s famous quote “critique by building”), can we counter the very concept of hegemonic monumentality, do we each decide on our own what to do, do we each do something different? Who are “we” and what are we (each) doing here?

Rodolfo Marron III’s customized galletas at Diana’s Bakery.

Curator Katherine Simóne Reynolds generously takes the time to speak with me. I ask her how it was to collaborate with all of these artists, local spaces and businesses. She says, with a dry laugh, “Complicated.” I can only imagine, for example, the extensive conversation and collaboration that Rodolfo Marron III’s customized galletas, sold through Diana’s Bakery to benefit Latinos en Axión, and Thomas Kong’s project, which gives those who purchase an item at The Economic Shop a plastic bag piece made by the artist, have required. Both Reynolds and the Luminary co-director Brea McNally tell me that organizing and curating this triennial has been unbelievably exhausting; the team has been tasked with framing, constructing, and coordinating this three-month project, through which almost every artist’s work takes a different form. They have had to react to last-minute fiascos, solve unique installation problems, pursue sponsorships and permits, deal with artist gallery representation schemas, and handle many other tricky elements of commissions, discursive events, projects, and performances. Reynolds tells me that she has had to ignore her own body’s cries for rest and respite throughout the process. I do wish that these “private” and “behind the scenes” processes were more visible during and as part of the triennial, themselves recognized as crucial aspects of “counterpublic” activity.

Chloë Bass, This is a Film, 2019.

Chloë Bass, This is a Film, 2019.

Chloë Bass, in her performance lecture This is a Film, quotes Darryl Pinckney, telling us that, “Art is control and it is also self-control.” While the idea of “control” may first seem wholly negative, controls are also a part of intentionality and compassionate interaction. Self-control is also often the force which keeps organizers and artists working, making work, mobilizing, even when the tasks seem insurmountable and innumerable. COUNTERPUBLIC arches its back within the controls of capitalism, which assures that there is never enough money for radical praxis, that artists and organizers exploit their own time and labor, and that artistic processes remain product-oriented. Reynolds points out that being able to pay these artists fairly and bring them (mostly from outside St. Louis, quite a few from NYC) into contact with this mid-sized Midwestern city and to offer their work for free already feels wonderful. When and where personal and social pleasure-orientations (a la Adrienne Marree Brown and many other Black, Latinx, and/or Queer Feminist theorists) are merged with controlled (intentionalized) political resistances and re-ma(r)kings, projects such as this one find ways of navigating ethical considerations that may be contradictory, even mutually exclusive on theoretical and political levels.

This triennial is working hard to self-reflexively acknowledge its difficult position. Few contemporary artists or arts institutions can afford (literally) to wholly resist participation in the public orders of “the” dominant artworld, but many are well aware that these orders tend to force artists and audiences alike to publicly value ourselves and each other on imperial terms, to narrate personal experiences using the languages of oppressors, to give up ancestral ways of living in exchange for resources, and otherwise establish bodily capital value within the parameters of public markets. It is difficult to tell which “artworldings” are part of “the dominant public sphere” and which are part of “counterpublics,” especially as “the artworld” (and by “the artworld” I mean the forms of artistic production and exhibition operating within global market economies) frequently frames and brands itself as a sort of massive counterpublic in its own right, commercializing dissent and commodifying critiques of “the state establishment” by transforming the invisible, unknown, and excluded into luxury experiences and objects. COUNTERPUBLIC (as well as The Luminary) has great power in Cherokee and in St. Louis, and that power crackles tensely between respect for local perspectives and pleas for global presences, between criticality and constructivity, between control and support, capital and conscience. Reaching beyond cordoned-off and highly-controlled “autonomous” artworldings however, COUNTERPUBLIC extends into civic involvement through a Q & A with an Alderperson and, during Cherokee’s annual Cinco de Mayo, dissolves into cultural practices that flood out the triennial with other posters and banners, food trucks and tents, concert stages, and the People’s Joy Parade.

Further, by inserting works like Jeremy Touissant-Baptiste’s Get Low and Sky Hopinka’s videos Jáaji Approx and Wawa into businesses (St. Louis Hop Shop, phone shop Communications Depot, and Don’s Muffler, respectively), COUNTERPUBLIC straddles multiple publics, worlds, and positions. These two artists especially encourage poignant personal reflection within existing public spaces of transaction, inviting those who experience the work into states of aporia, acknowledgement, and rapid internal movement between analysis and emotional abreaction. The “guiding” theatricality (in Michael Fried and Thomas DeFrantz’s senses of the term “theatrical” as forms of self-recognition and controlled “leadings” of spectatorships) of COUNTERPUBLIC feels earnest, actively inviting criticism, welcoming agonistic conflict, and implicating many different contextual locations in a hyper-sensitivity to multiplicit site(s), sights, and situations.

***

As COUNTERPUBLIC continues to unfold and process its own public presences, I look forward to experiencing the rest of the exhibition, a closing performance by NIC Kay. This ambitious, theoretically dense, and often breathtaking triennial has encouraged me (and, I think, quite a few others who have experienced it so far) to dig more fiercely and courageously into questions of public memory, visibility, and memorialization, geo-politics, power, representation, and the fraught positions of artists and cultural organizers (as well as witnesses, participants, critics, passers-by) as performers of diffractive, conflictual, transient, and transformative public and counterpublic worldings.

COUNTERPUBLIC runs through July 13, 2019 in St. Louis, MO. More information, maps, and event schedules can be found on counterpublic.us. More images, video, and documentation can be found on IG @counterpublic.

Related Articles

Terms of Engagement: Quality Art-Worlding, and how Performativities Work, Part I

What's Your Reaction?

Founder of Panoply Performance Laboratory (PPL). PPL is a flexible collective, think-tank, and lab site in Brooklyn. PPL's "operas of operations," performance art, installation, and social projects deal with world viewing processes and organizational forms through direct practice. Neff also makes solo performance, operates as an independent researcher, organizer/caretaker, and theorist. l Instagram l Twitter l Website l