Cynthia Talmadge Brings Marilyn Monroe’s Chaotic Relationship With Psychoanalyst Ralph Greenson to Life at 56 Henry

Cynthia Talmadge’s latest solo show Franklin Fifth Helena at 56 Henry is nothing short of a great story. An immersive, architectural installation, Talmadge has created a psychologically complex, visually engaging, technically stunning domestic room. Made entirely of sand paintings, the installation explores the wild, toxic relationship between Marilyn Monroe and her psychoanalyst Ralph Greenson, a topic that has been the subject of countless conspiracy theories in connection to Monroe’s death.

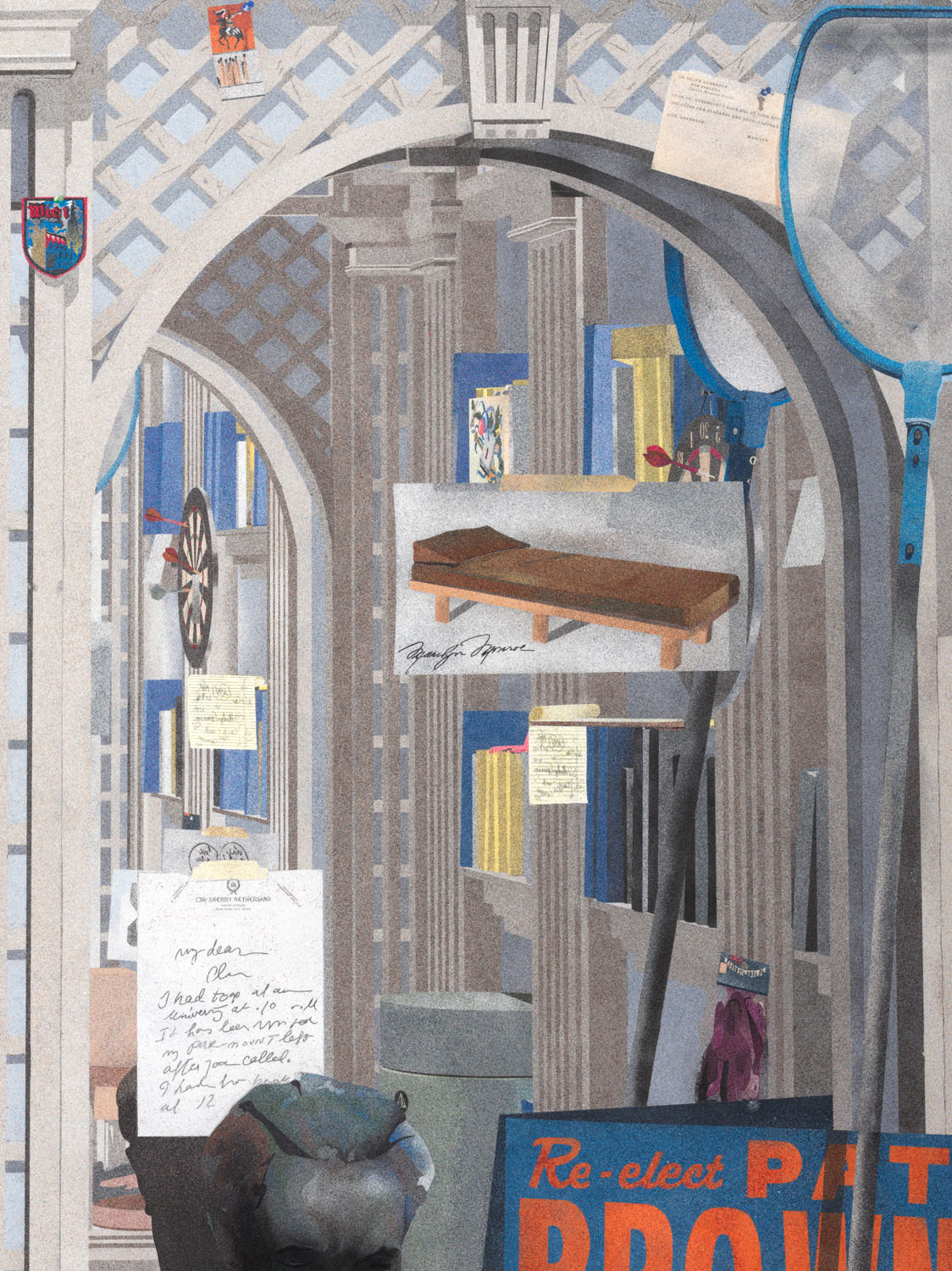

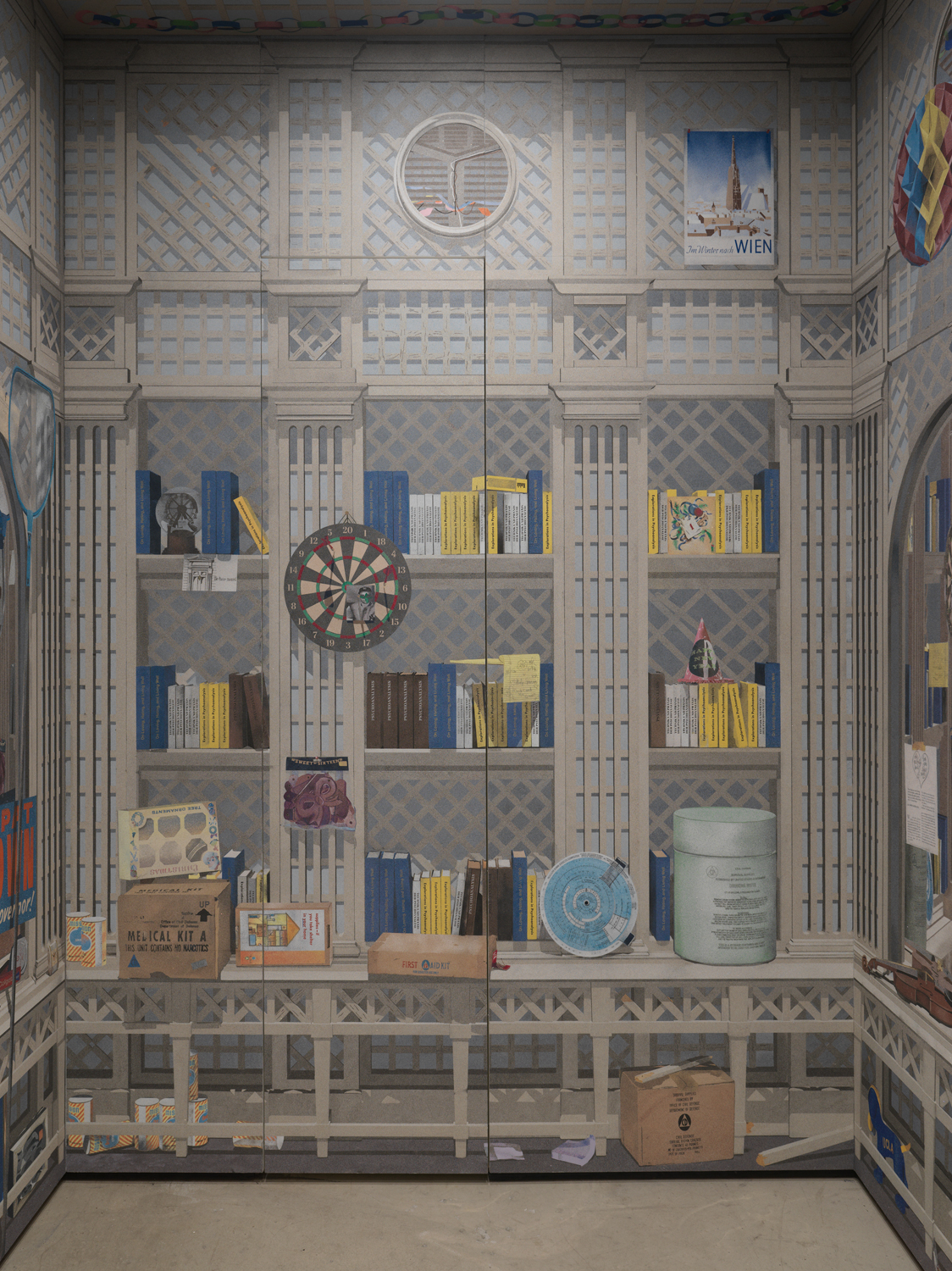

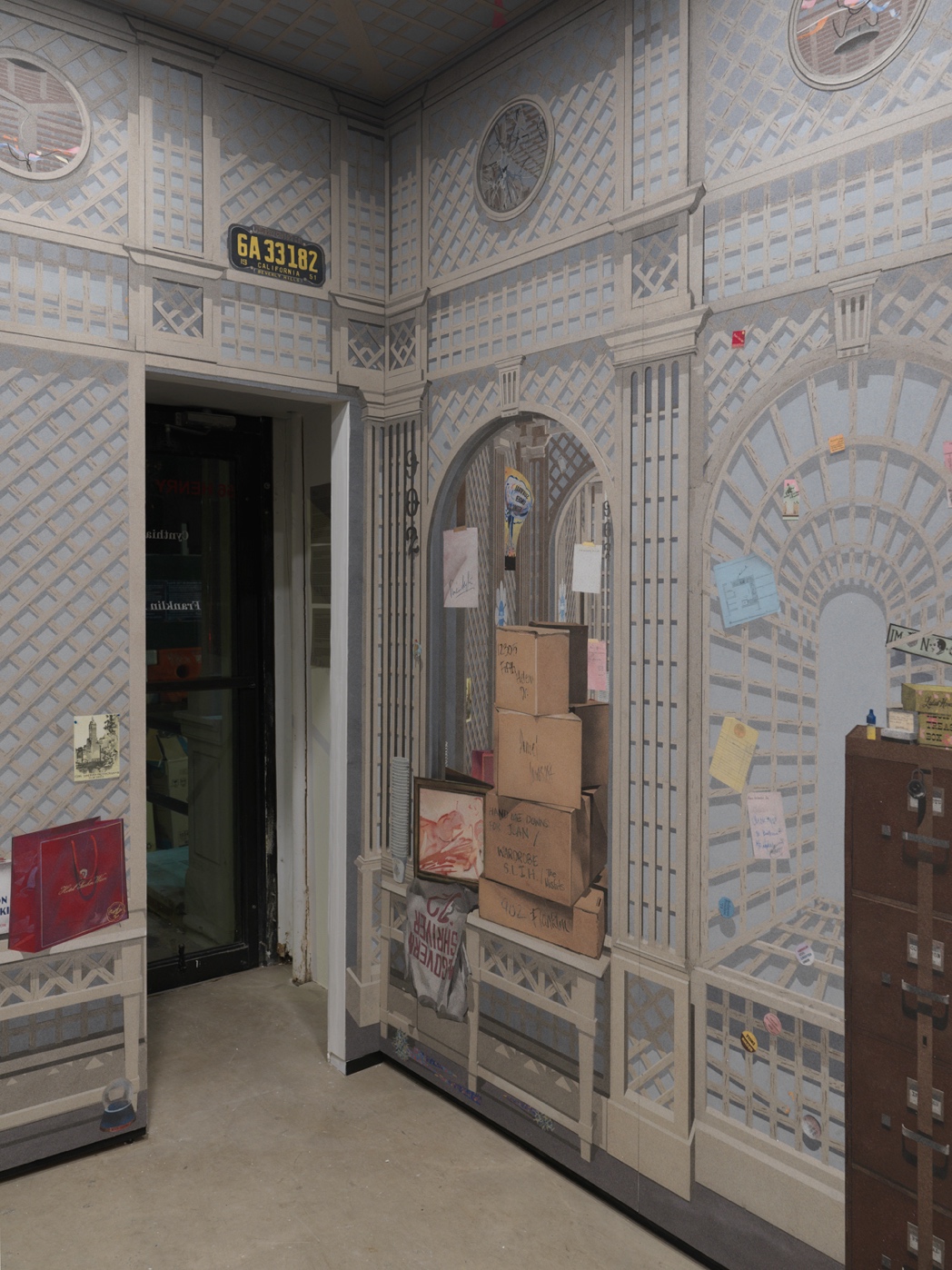

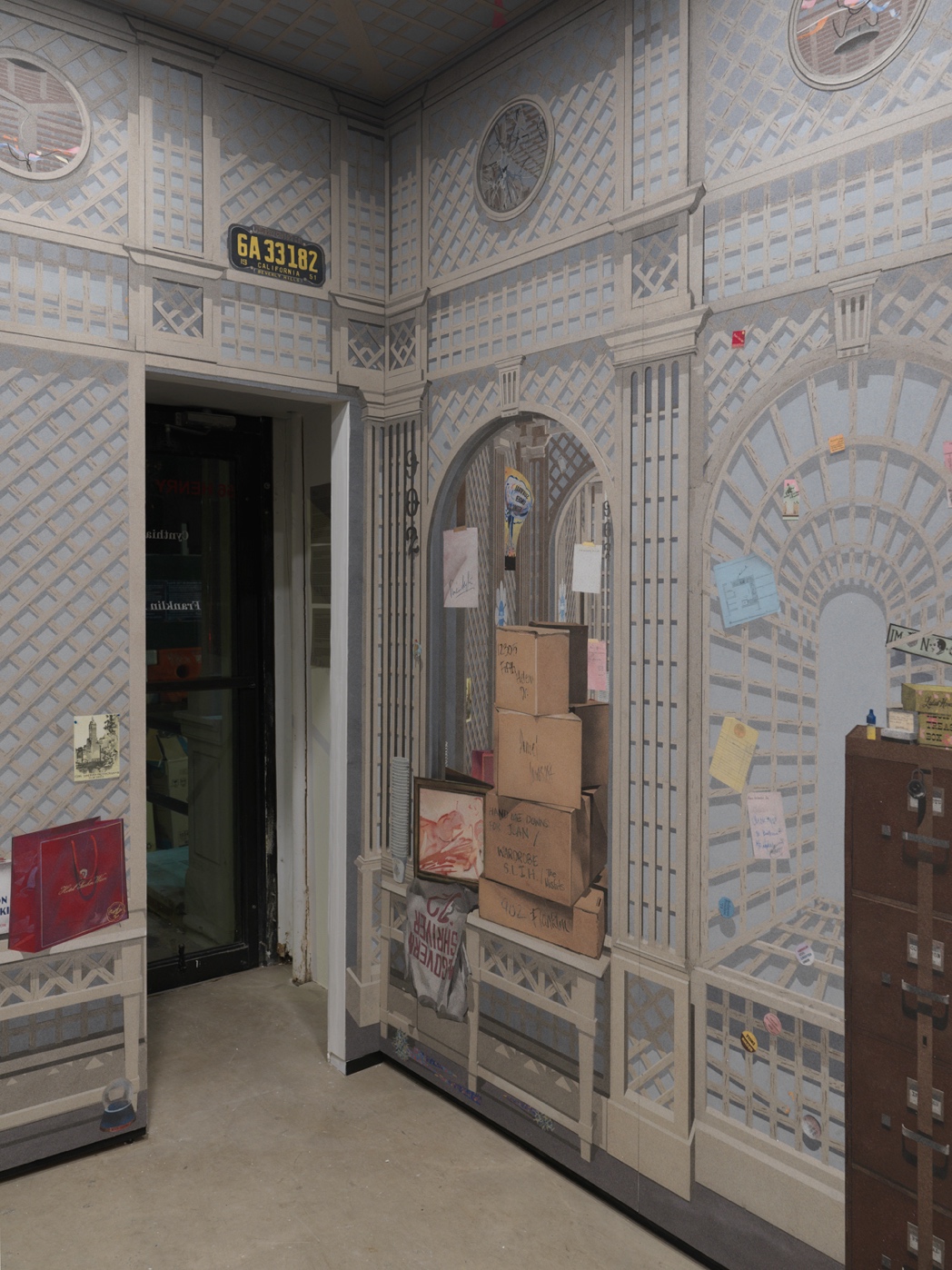

Franklin Fifth Helena is rife with information. There are visual cues and subtle hints across the room, which is in the style of the 15th century Gubbio Studiolo, the famous study decorated with wood-inlay displaying cabinets full of the owner’s objects including books and scientific objects. Borrowing the studiolo format, Talmadge has meticulously covered the walls and ceiling with highly detailed sand paintings.

-

Cynthia Talmadge. Franklin Fifth Helena. Sand painted installation, 2021. Photographed by Matt Grubb. Parsing the objects and the room itself takes careful consideration. Talmadge offers no logical pathway or roadmap to understand the narrative, or if there even is one. For a visitor who isn’t familiar with the story of Monroe and Greenson, the room might appear to be part storage, part shrine to mid-century American culture. At the same, those who are familiar with their relationship will bring in their own theories and expectations of the visual cues they will, or want to, see.

One object stuck out as a point of entry: a book titled “La Femme Frigide” by psychoanalyst Wilhelm Stekel. Visible among several psychology books, “La Femme Frigide” appears multiple times in the room. Stekel, a famed follower of Freud, advocated for a form of therapy that was intended to rid patients of childhood traumas by replacing their negative memories with positive ones.

Talmadge’s inclusion of Stekel’s book points to Greenson’s own controversial application of this therapy in his treatment of Monroe. In replacing the damaging memories, the idea was to pick a model family upon which to base new experiences. Crossing all boundaries of professionalism, as part of Greenson’s treatment of Monroe, her model family was the doctor’s own. Monroe had to develop relationships with Greenson’s family, visiting, dining, and sometimes living with them. She was also made to recreate parts of Greenson’s house in her own, which is the room Talmadge reimagines in Franklin Fifth Helena.

Talmadge’s room thus blends elements of both Monroe and Greenson’s homes. The exhibition title nods to the two famous residences, the first and most prominently featured is 12305 Fifth Helena Drive, the Brentwood residence that was the final home of Monroe and where she was found dead in 1962. Greenson’s home was located at 902 Franklin Street in Santa Monica.

Like a game of “I spy,” the viewer is invited to explore the visual cues of mid-20th century popular culture and Monroe and Greenson’s relationship. There are boxes labeled “dream diaries” and “exercises for Dr. Greenson”, and shelves packed with books. Alluding to self-preservation and improvement, there are several first aid kids, a box that reads “supplies if you take shelter in your home,” and various references to atomic bombs including a poster of a mushroom cloud and an instrument that reads “nuclear bomb effects computer.” Nearby, there is a locked file cabinet whose labels are obscured, leaving the viewer to speculate on the contents. Ephemera from iconic LA hotels and restaurants like matchbooks from the Beverly Hills Hotel, Musso and Frank’s, and the Polo Lounge, are scattered across the room and pinned to walls.

-

Cynthia Talmadge. Franklin Fifth Helena. Sand painted installation, 2021. Photographed by Matt Grubb. Some items appear to be from Greenson’s life, like the psychology books, while others appear more likely to be associated with Monroe, such as a “ladies home journal recipe treasure box”. Others are more ambiguous. One wall contains a dart board with a photograph of a Yankees baseball player with his face obscured pinned on the center. Perhaps this is a loving commemorative image of Monroe’s ex-husband Joe Dimaggio, or perhaps it bears negative sentiments as a target for Greenson jealousy. Some speculate that Greenson was obsessive over Monroe and that their professional relationship was also a sexual one.

As the site of Monroe’s death, 12305 Fifth Helena Drive brings with it layers of history and conspiracy theories. While beliefs on Monroe’s death vary, one prevailing speculation is that Greenson murdered, or helped to murder, Monroe, possibly under orders after she threatened to reveal her affairs with John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert F. Kennedy.

Cynthia Talmadge. Franklin Fifth Helena. Sand painted installation, 2021. Photographed by Matt Grubb. References to politicians from both the Democratic and Republican parties are woven throughout the room. There’s a psychedelic flower celebrating former senator Eugene McCarthy, a sign to re-elect former California Governor Pat Brown, a bumper sticker that reads “impeach Nixon” in a mixture of letters and symbols, and a pin that reads “McGovern President ’72”.

The contradicting political beliefs of the names promoted and the dates of the various events referenced, some of which occurred after Monroe’s death, are important to note. Subtle details like these point to the ambiguity of the room itself. Are these mementos from Monroe’s life, or Greenson’s? Or neither?

Much like conspiracy theories in general, Talmadge’s presentation is her own interpretation of the facts, fantasies, and hypotheses uncovered over the decades. Who added these items, when they were added, and if they were even real is all unknown. As unsolved as the circumstances of Monroe’s death and her relationship with Greenson, the meaning behind the contents of the room are left up to the viewer to decide.

Franklin Fifth Helena is on view at 56 Henry until January 30, 2022.

You Might Also Like

As Deitch Cements Exhibition Curated by AJ Girard We Quiz Him on the Art of Self-Actualization

TagsWhat's Your Reaction?

Excited0Happy0In Love0Not Sure0Silly0 Annabel Keenan

Annabel KeenanAnnabel Keenan is a New York-based writer focusing on contemporary art, market reporting, and sustainability. Her writing has been published in The Art Newspaper, Hyperallergic, and Artillery Magazine among others. She holds a B.A. in Art History and Italian from Emory University and an M.A. in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center.

-