Eraser, Erase-her: Censorship of the Female, an Interview with Caroline Wayne

In 1972, A.I.R. Gallery opened its doors as an all-female artist-run non-profit cooperative to give visibility to female artists and provide a forum for them to take risks that would not be supported by mainstream institutions. Forty-six years later, on a cold spring night during a reception, I still found crowds of women of all ages heatedly discussing many of the same limitations that had inspired the foundation of the non-profit. Chiefly, the barriers female artists encounter while seeking visibility and, the frustration of being continually blocked from speaking to their own position un-censored.

The clamor of the room quieted dramatically as an artist by the name of Alli Melanson began reading aloud a bristling passage about the feminist icon Hannah Wilke, from Chris Kraus’ cult novel “I Love Dick” (Semiotext(e), 1997) – a text that achieved literary notoriety for “marching boldly into self-abasement,” in the words of poet Eileen Myles, and for investigating the limitations put on intelligent and ambitious women.

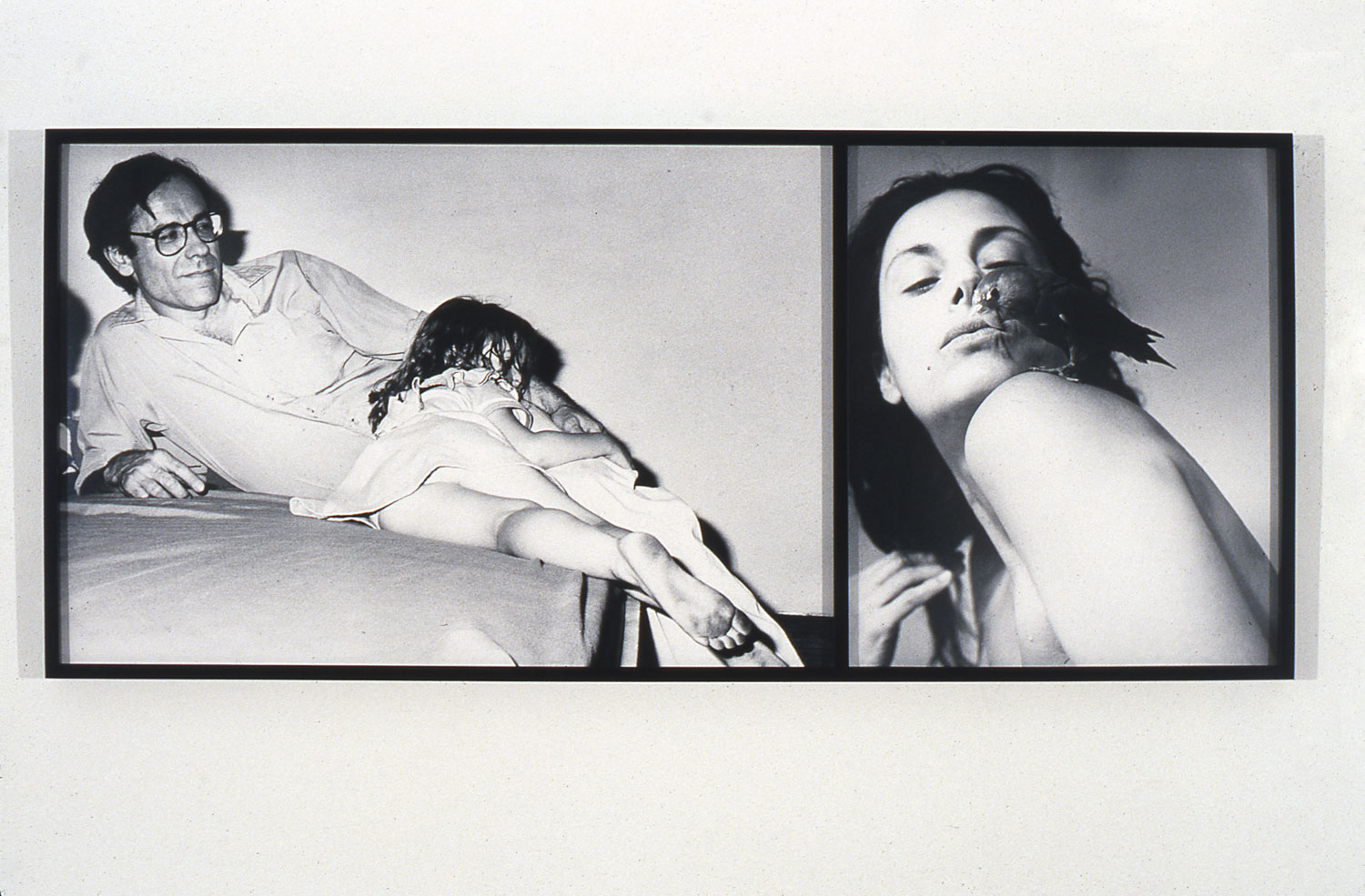

Previous: Caroline Wayne. “Disarming,” 2018. Felt, beads, and sequins on Soft. All photos courtesy of the artist if not otherwise stated. Above: Hannah Wilke, Advertisement for Living: Daughters, 1975-82, diptych, black and white photographs on rag board, 28 x 64 inches overall. Photographed by Lisa Kahane courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

In 1989, Kraus details how the artist Hannah Wilke experienced an embittering blow when a significant portion of the art and writings accompanying her first major career retrospective was censored by the University of Missouri Press – at the behest of her more famous former lover, Claes Oldenburg. Oldenburg wanted any mention of himself to be excluded from her retrospective “out of respect for his privacy.” His request also included that certain artworks be excluded, such as the “Advertisement for Living: Daughters,” 1975-1982, as it included a photograph of him and the artist’s niece.

The artist’s work frequently involved having those closest to her, like Oldenburg, photograph her in seemingly sexualized or objectified poses in an aim to reverse the voyeurism inherent in women as sex objects. Wilke had lived, worked and traveled with Oldenburg for nearly a decade – comprising a significant portion of Wilke’s professional career. Oldenburg’s request – which would become notorious as an act of female marginalization – was honored by the University and the impact would influence Wilke’s work for the rest of her career.

“Claes’ fame and the University’s unwillingness to defend her made it possible for Oldenburg to erase a huge portion of Hannah Wilke’s life. “Eraser, Erase-her” – [became] the title of one of Wilke’s later works,” Concluded Melanson solemnly from Kraus’ text, ending with a reminder that Wilke had famously never “let it go.” Neither should we.

Caroline Wayne. “Choke,” 2018. Felt, beads, and sequins on Soft.

It was then that I met the artist Caroline Wayne, who, dressed in black and buttoned to the neck, turned to me, and shrugged, “you think you would [fight it], but it’s not so simple.”

Wayne’s marvelous and haunting show, “Pretty Real” was glittering on display in the gallery behind her; a group of intricately-beaded sculptures depicting dream narratives – offered like-bejeweled reliquaries of her most intimate and painful experiences.

Wayne as an artist and as a survivor of domestic abuse has chosen a life committed to “radical transparency,” an extreme and unflinching commitment to truth which has earned her countless censorship flags, and cost her more than one relationship but also freed her. “Brute honesty” has become an integral aspect of her sculpture, virtual work and writings. Her open diary Elegant Hustler, is a striking example of the transparency that she hopes will empower herself and other women.

Caroline Wayne, “Was it Something I Said?”. Felt, beads, and sequins on Soft, 2012.

Like many female artists before her, the works Wayne makes that explore the conditions of her gender, by employing behaviors commonly used by men to dominate women, are constantly being shut down for violations of “community standards.

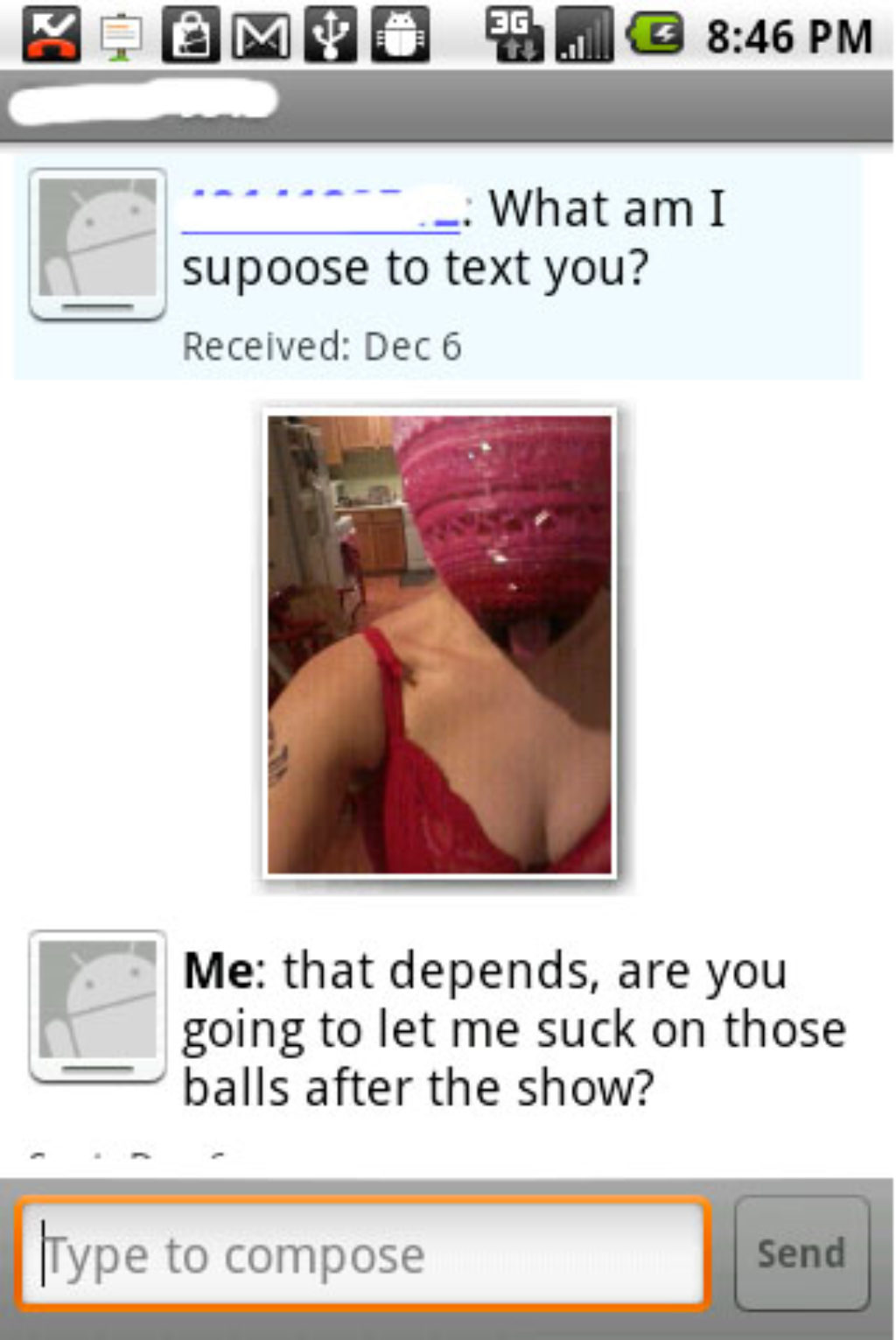

”For example, in 2013, while she was a student at the School of Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) Wayne experienced her first bout of censorship when a part of her work “Was It Something I Said?” was censored in the annual BFA show. Conspicuously, the same work had been shown within the SAIC program earlier in the year without issue. The piece consisted of a heavily beaded, gimp-like, eyeless mask – a sole receptacle extravagantly rendered in sparkly, girly-pink beadwork. Concentric circles of red and pink concentrated toward the mouth give the appearance of a flesh-toned, penetrable opening. The mask was displayed on a stand paired with a phone number and a beaded invitation at the base: Text Me.

Excerpt from a conversation. Caroline Wayne,“Was It Something I Said?”, 2012.

The phone number connected the audience to the artist. If a game art viewer chose to text, the artist would send the participant a suggestive photo of herself wearing a brassiere and the displayed mask to initiate “sexting.” The objective was to increasingly graduate the conversation to uncomfortably aggressive, sexual and violent extremes to exercise what the artist refers to as “topping from the bottom,” a tactic of subversion that remains central to the artist’s work today, investigating how the chronically abused learn to manipulate to survive while appearing to submit.

The piece challenges the primacy of the texter – who is ultimately seeking engagement with an inhuman, feminized receptacle – suggested by the sole feature of the mouth’s beaded opening. Control is taken instead by Wayne’s new female fiction of an extremely harassing, strange, and frightening aggressor who comes to dominate the exchange with a barrage of her own insatiable needs. This is a reversal that any woman who has experienced frightening, harassing, and disturbing solicitations from male aggressors can darkly appreciate. The work also successfully pushes the fiber-arts medium beyond the decorative/performative into the virtual, as well as into a refreshing provocative critical space.

Caroline Wayne, “Was it Something I Said?”. Felt, beads, and sequins on Soft, 2012.

None the less, after one night on display, SAIC’s management allegedly received a complaint from a person of influence and removed the solicitation to text from the work, effectively stripping away the work’s conceptual component and its location in the virtual. This relegated the remainder of the piece to its purely decorative craft.

Next, the school summoned Wayne and deployed an insultingly common pretense of concern over a woman’s safety to infantilize an adult and restrict her autonomy. The SAIC’s “Art School Considerations Committee” insisted that Wayne had endangered her safety, ignoring the many reasonable precautions she had taken to protect herself and informed her that if she resisted or protested, they would need to involve her “emergency contacts” (i.e. her parents) while intimating she may not graduate if she did not hand over the pre-paid cellphone records of the project. The humiliating intimidation campaign left Wayne feeling diminished and not trusted as an artist or as an adult, but as she had invested both work and money in her degree and was only a few weeks from graduating, she complied.

After the opening, I caught up with Wayne to pick apart what is so threatening about a woman’s self-exposure:

Louise Hohorst: Do you think there was any ground for SAIC to censor “Was it Something I Said?”

CW: While “Was It Something I Said?” may have been shocking to some participants who chose to text the number at its base, they still elected to engage with a prompt in a gallery setting and throw themselves at the mercy of performance art – a medium that more often than not leans political and intends to push its audience through the power of human experience. Given how often eroticized women are, it should not have been out of bounds.

LH: Hannah Wilke’s anger over the censorship issue is well known and engendered a lot of criticism from contemporaries that she wasn’t, I guess, a better sport about it. Everything you make is completely personal – from this experience with SAIC, to your numerous flags on other virtual platforms have you somehow just found a way to live with censorship?

CW: No. Being censored is a frustrating feeling. It’s not quite like the feeling of being invisible, because you’re well aware that you’ve been seen. Instead, there you are in plain sight, fully assessed, then actively ignored. It’s the ultimate rejection. And, since my art is usually just an expression of my own reality it then feels as though my whole life experience itself is being invalidated. It’s diminishing, and it’s enraging and it’s personal. You don’t get used to it.

Sexualization and straight objectification of women is absolutely allowed under Facebook and Instagram’s guidelines as long as its part of an advertising fantasy.

Caroline Wayne

I’ve been flagged [on Facebook] by people I knew from high school for jokes about reverse cowgirl, but they were posting pictures of their babies actually shitting. Those kids don’t have the ability to give consent, I do as an adult. People don’t tolerate real truth about anyone else and I hate that. I don’t buy that it’s about modesty and sex stuff, because you know what? Sexualization and straight objectification of women is absolutely allowed under Facebook and Instagram’s guidelines as long as its part of an advertising fantasy. But, its somehow horrific if I, as an adult woman talk about that aspect of my life. It’s twisted.

LH: In your situation with the SAIC, you have been very candid (as always) about the fact that you didn’t fight it at the time, although you certainly had the case for it. I know that you were younger then. What was going through your mind?

Caroline Wayne, “Splash,” 2018. Felt, beads, and sequins on Soft.

CW: Listen, some people have success making noise and escalating the fight in real time, turning up the heat so high that the oppressor has no option but to back down in the end and submit to the pressure. Maybe it’s just been my own history of knowing certainly that I’ve never had the option of winning. Being a child in a home controlled by my abuser, I was isolated and limited. I learned to channel my rage about everything horrific and unjust into new skills. I’d need to succeed once I found the avenue for it.

When I faced the initial acts of censorship from the administration, being called into the Assistant Dean’s office and demanded to turn in my SIM card, I went into a state of self-preservation. I knew this was a huge violation of my rights and I fought it initially. But, it was clear that between me and an institution like the Art Institute of Chicago I was not going to win. Like many times in my life dealing with a bigger, physically stronger, or more powerful force than I can logically fight against my immediate instinct is to placate in order to survive the confrontation. This is a reaction built in from 30 years of being attached to an abusive relationship. Knowing misogyny intimately, to its very rotten core, and having learned how to cultivate the skills to subvert its oppressive hand. I’ve found at times it’s easier to lose some battles in order to save myself. Just placate, then work fastidiously on my own end, maybe even in secret, towards my own redemption, my own way out. It’s how I’ve developed tactics of subversive sex and written a whole website about topping from the bottom both physically and psychologically. It’s actually the foundation of how most of the language I used in the texting portion of this project came about, the root of my sexual self-empowerment.

I’ve had discussions with other women about what to do with our rage right now and a lot of it ends up going to self-care and community care. Strength doesn’t necessarily come from winning a fight, sometimes it’s just in the ability to survive it.

***

What I find fascinating about this triangle of women is that like Chris Kraus, Wayne forges through a dichotomatic coexistence of vulnerability and empowerment through the brutal transparency of her writing, and similar to Wilke, she has employed photography of herself in seemingly sexualized or objectified poses that are misunderstood as a form of self-debasement. In reality, all three expose the conditions of their own degradation. By reading these feminist works as objectification instead of explorations of degradation, critics remove their critical and intellectual agency – this removal of the right to speak is an act of censorship.

Thank you to artist Caroline Wayne for allowing us to share your story. Thank you as well to the editor Anna Mikaela Ekstrand, to A.I.R. Gallery for creating a forum for meaningful discussion, and to Cultbytes, the female-owned art blog promoting new perspectives.

Do you need help resisting art censorship? Consult the National Coalition Against Censorship. If you want to share an experience of censorship please send us an email.

What's Your Reaction?

Guest Writer, Cultbytes Investor Relations Specialist and former art world professional. Before transitioning to the financial sector Hohorst held a position at Artsy, the Smithsonian, and organized multiple exhibitions in her capacity as a curator at the Dealer's Lounge. Now, Hohorst is a senior investor relations associate at ICR Inc. Her volunteer work includes student-peer counseling to foster healthy relationships and tackle domestic abuse. She graduated with a BA from Skidmore College. l igram |