Agnès Varda, To See the World Through Your Eyes

The celebrated French cinéaste, Agnès Varda’s (1928-2019) prolific, trailblazing career spanning more than six decades produced a body of work that is poetic, lyrical, and unmistakably iconoclastic. At the newly opened Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles, Agnès Varda: Director’s Inspiration unravels the real-life snapshots that met the New Wave director’s camera lens whose work lies at the intersection of documentary and film. The exhibition reflects how Varda not only imbues the everyday with an emotive tenor but also adds a touch of humor, optimism, and lightheartedness to a diverse range of themes: from feminism to counterculture, from romance to obsolescence.

Through contact sheets, set photos, objects, and handwritten notes, this exhibition aptly demonstrates how Varda diversified the ways of looking by thinking of pictures as an ideological apparatus superimposed onto the realism of life.

As part of the museum’s central presentation titled Stories of Cinema (referencing Jean-Luc Godard’s 8-part video project), Director’s Inspiration is situated amid other rotating exhibitions featuring Casablanca and The Godfather. Upon entering the gallery, the mustard yellow and cerulean blue on the walls immediately remind me of Le Bonheur (1965)—in which vivacious summer hues are ever so slightly subdued. The azure is like a love letter to the beach, which Varda described as the perfect theater of the sky, the ocean, and the earth. The wall to the left of the entrance is divided by a mirror and a pedestal, into two sections: “Photography” and “Art” (mostly paintings in this context). At the center of the room, three large screens show excerpts from her movies in a chronological sequence, which is then followed by another section titled “Real People, Real Life” to shed light on her personal musings and chance encounters.

Before her cinematic debut La Pointe Courte (1955), Varda worked as a photographer. Unlike how Godard would have been informed by Dziga Vertov or Jean Cocteau, Varda did not look to forerunners in the film industry as her primary source of inspiration. She neither received specialized training in film school nor followed the standard path of progression through the ranks of assistant directors. Her unconventional path towards filmmaking would afford her the freedom and independence to cultivate a unique style underpinned by photographic sensibilities. She would go on to layer dialogues over stills and have a narrator speak for minutes before directing the viewer’s attention to the next image.

The “Photography” section includes some of the most seminal examples of this priority given to stills. I was particularly excited by the original photograph from Ulysse (1982), accompanied by the gouache painting modeled off of the photo. The 22-minute film problematizes how media factors into the construction of meaningful memory. By conducting interviews with the protagonists in a 30-year-old photo, Varda reveals that the notion of concrete visual memorabilia is fundamentally a fallacy because the boy, Ulysse Llorca, remembers neither the beach nor being photographed. The represented reality, therefore, is incompatible with the boy’s own version of reality. Further, when depersonalized, the boy can even be read as an archetypal Oliver Twist or Little Prince. The photos, or many photos shown in this section, are emblematic of how Varda’s cinematography complicates the backstory of images.

Similarly, Varda’s frequent art historical references in her films address recurring motifs related to representation, temporal ambiguity, kitsch, and disjunction. Think about her references to Titian in Jane B. by Agnès V. (1988), to Willie Herrón in Mur Murs (1981), or to Picasso, Magritte, and Warhol in Lions Love (…and Lies) (1969). The art/paintings section of the exhibition includes an iconic pastoral painting by Millet to echo how Varda landed on gleaning as the overarching concept in The Gleaners and I (2000). This is where images—historical and contemporary, symbolic and personal—acquire convoluted meanings implicated in sustainability, poverty, and even filmmaking (for instance, Varda would go on to say that she, a filmmaker, was a gleaneuse of images).

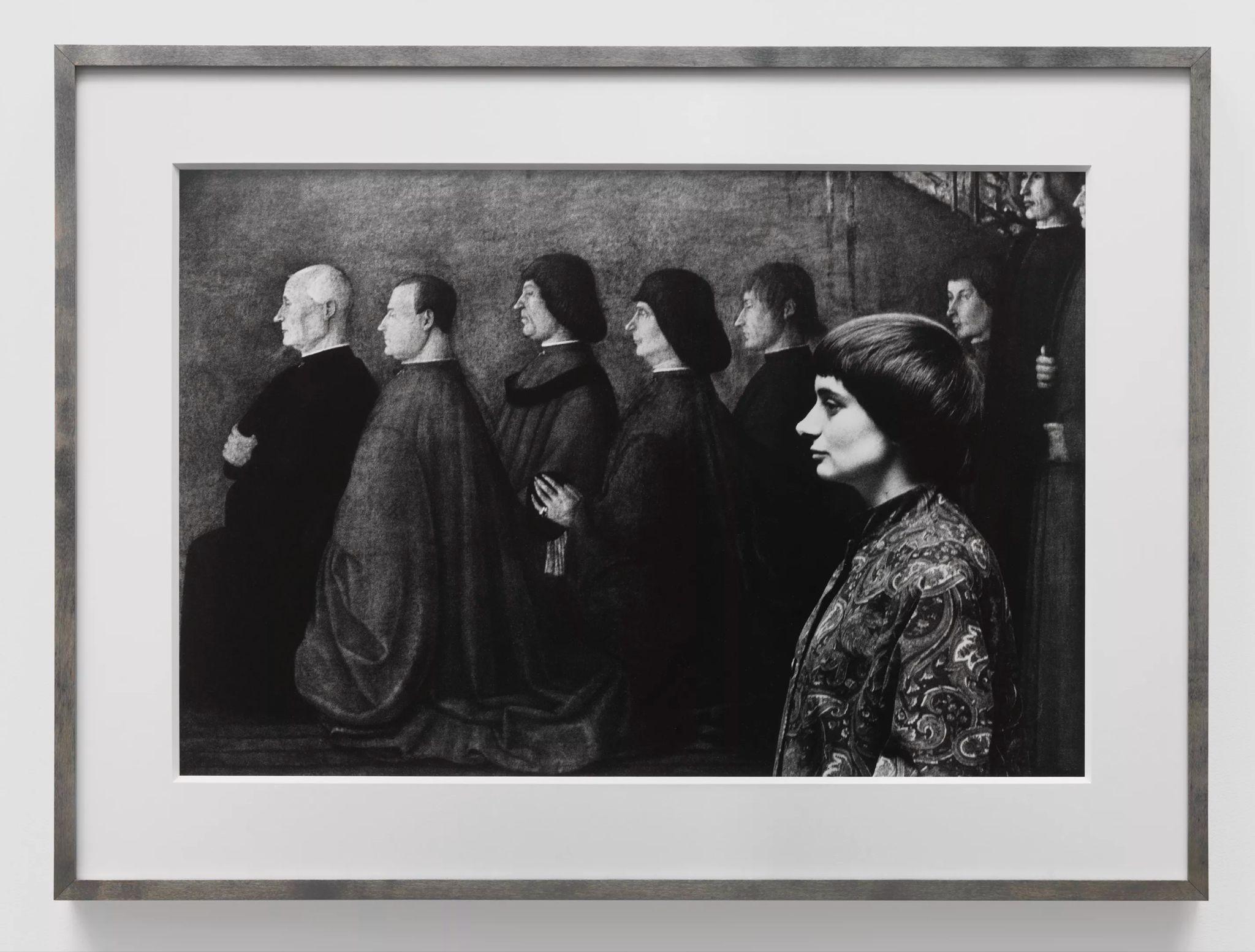

Her auto-portrait series hearken back to Byzantine mosaics and Gentile Bellini’s The Miracle of the Cross at the Bridge of San Lorenzo. The playful introduction of her face into these images allowed her to engage with the political dimension of aesthetics. Even the three-panel video display refers to Varda’s dialogue with triptychs in ecclesiastical art, directly alluding to how she displayed Patatutopia as part of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s Utopia Station (2003). Images, many of which are commonplace or inconspicuous, deserve and are capable of an elaborate process of reinterpretation to generate new meanings.

In the final section, the personal inspirations are presented in readily digestible forms: the miniature of her and Jacques Demy on a train, the “Viva Varda” and “I Like Uncle Yanco” pins, and the release forms signed by Black Panther leaders. For some reason, seeing these objects in a museum setting reverberates how she thought of documentary films: presenting reality with a mise-en-scène kind of twist. And then you look at the empty Agnès V. chair on the pedestal with a cat on the side. Everything starts to make sense. You can see her sitting on it. If you saw Varda by Agnès, this chair would create a mental picture and mark the gallery as Varda’s beach or her auditorium. This lingering afterthought perfectly illustrates the power of visual symbols and their periphery.

Director’s Inspiration presents a fascinating survey of the iconic French director’s cinematic thinking. Obsessed with how images are presented and how they participate in social, poetic, and artistic dialogues, Varda proposed a reconsideration and expansion of their interpretive capacities.

Agnès Varda: Director’s Inspiration is on view at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures until January 5th, 2025. The show’s eponymous catalog will be available in November 2023.

You Might Also Like

Memoria: On Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Surreal Meditation

“Another Kind of Knowledge” Portrait of Dorte Mandrup Explores Architecture Beyond Language

What's Your Reaction?

Xuezhu Jenny Wang is a multilingual translator and content creator. In addition to writing about postwar and contemporary visual culture, she is working on a research project that focuses on mid-century interior design and mechanization.