Interview with Tulu Bayar: “A Space With No Border”

“London is an exotic city to me, I love it but it is not mine,” the multi-media artist Tulu Bayar explains when I ask her if London feels like home. The artist spent a semester teaching there and will be spending the Thanksgiving holidays in London, convening with friends and collecting raw material for her digital archive. We are speaking on the phone about her current exhibition “Twine” on view at Amos Eno Gallery in Brooklyn. She continues, “When places become mine, I have like and dislike positions. There is both push and pull. Turkey and the U.S. are mine.”

As an immigrant, or holding multiple homes in general there is always a push and pull, a possibility to be in multiple places but the impossibility of being in them at once. Visitors to her exhibition are met by a large scroll on the back wall, upon entering—” the top is the future, the middle is the present, and when the end is revealed and it is rolling back, you can see the future,” she explains poetically. In addition, the scroll is found in many different cultures, Turkish and Asian, and across periods, including medieval material culture. Bayar appreciates its universality. “Scrolls are a good bind for the whole exhibition, mediators, to represent the continuous city,” she says. The scroll interacts well with her interest in Rumi’s philosophical claim that everything is connected, the time also lapses.

Tulu grew up in Ankara and lived for some time in Istanbul, Turkey, before going to the U.S. for graduate studies, an MFA, in Cincinnati. She did not intend to stay, but came across interesting possibilities, “a natural flow,” she says, that took her to Los Angeles. There she found an international community, shared a space with three other artists, and had a darkroom. She was careful about disposing of the chemicals appropriately: “They know everything about you, they look at everything and guesstimate what kind of citizen you will be,” she comments on U.S. Immigration Services. Speaking to the arduous visa situation with “much ambiguity attached to the process, I had to be careful and pay attention to detail all the time”—especially following the September 11 attacks when processes became more complex and lengthy. After spending two and a half years in Los Angeles, Bayar wanted to find a more stable situation and explore the East Coast.

Bucknell University offered her a full-time position. “Moving from Ankara to Cincinnati and then on to L.A. was not a cultural shock—they are continuous cities; there are familiarities in the urban. What shocked me was Lewisburg. I had a rural shock,” she laughs. The tranquil postcard town where she picked up eggs from her Amish neighbors and home grown vegetables from others felt, in her words, “completely foreign.” Only a three-hour drive from Brooklyn she spends considerable time in New York City.

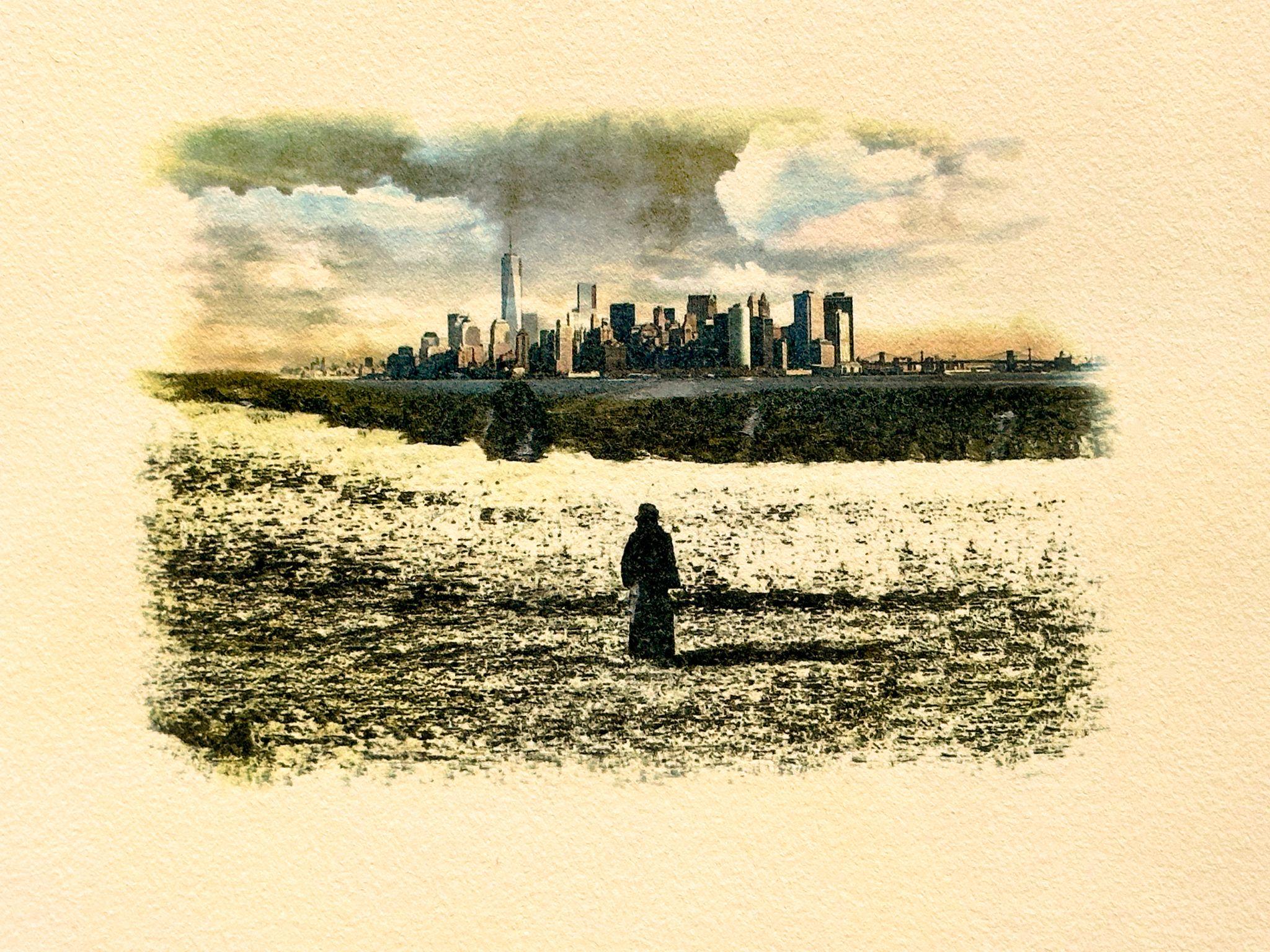

Bayar started as a photographer and has formal training in photography, media studies and old forms of video cameras and manual editing. In college, her minor was visual arts, which helped her to move to other artistic media over the years from traditional photography. And after graduate school she found herself practicing art unbound by the media as she employs various techniques that fit her concept-based work best. For example in “Twine” she has developed a sustainable and environmentally friendly Citra transfer technique—transfers made by using citric acid. Bayar found her way to this technique after searching for kinder materials after overcoming breast cancer. The holistic process bleeds into the subject matter, a lone figure looking out over the cityscape.

After living in Lewisburg for two decades she feels completely at home. Geographically Istanbul lies between two continents: “hybridity is embedded in the culture,” Bayar explains. East and West entwine, embracing. “We are talking about an intrinsic hybridity which is rarely part of the everyday rhetoric or a common understanding,” she points out. But, it took her many years to reach this peace of mind, and patience with others. “People often project and share their preconceived notions and conceptions about one’s identity—the conversations are sometimes awkward as a result of it,” she says pragmatically. She used to get angry at the unintentional downright questions and comments regarding “other” identities but was getting tired of this anger. About four, five years ago she had a revelation: “When you express something with anger people do not want to take it in. Now I take the time to explain in detail and I can see that folks are very much interested in learning and hearing.” I asked if her visa situation is now stable—she adjusted to her U.S. citizenship after fourteen years in the country. I remark that it is easier to be patient and forthcoming without the stress of contending with the immigration system.

Next to the scroll on the back wall. A cacophony of porcelain and glass tea cups, Turkish coffee and espresso cups and mugs is installed on white trays on the wall and a low pedestal. The installation speaks to the large tea culture in Turkey which hails from the North but is present throughout the country. “People drink tea with sugar. So, I wanted to evoke the sound of stirring—ching-ching-ching,” Bayar explains, to represent the high-pitched sounds of Istanbul as a whole.

Bayar is building a family of her own in Lewisburg, her eleven-year-old son is “very much a proud American.” she explains, but also interested in Turkish culture. At home they celebrate all cultural holidays: Christmas, Ramadan, Rosh Hashanah, Diwali, and The Youth Holiday”—a Turkish tradition where kids take charge of the country,” she says. Bayar is not religious but likes the festive celebratory way of recognizing culture on the high holidays.

There is imagination and hope in Bayar’s new body of work, like Italo Calvino, whom she admires, there is poetry and whimsy. I am thankful to have been given a glimpse into the part of her immigrant story where she has found harmony. “Land has borders but the skyline does not. I look at the skyline in New York, Istanbul, and Pennsylvania and I see a space with no border,” she concludes.

Tulu Bayar’s solo show Twine is open at Amos Eno Gallery on 56 Bogart Street through December 3, 2023.

You Might Also Like

“Parasites and Vessels” Conveys the Resilience of Immigrants

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.