“Parasites and Vessels” Conveys the Resilience of Immigrants

As has been proven time and time again, despite the promise of “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” the lives of immigrants oftentimes entail a series of difficult compromises. Consisting of three video works and two sculptures, “Parasites and Vessels” takes place at Accent Sisters, a queer speakeasy bookstore in New Jersey. Presenting the work of Anna-Ting Möller, Young Joo Lee, Juna Skënderi, and Alexander Si, this group exhibition is concurrent with indigenous-Colombian-American artist Coralina Rodriguez Meyer’s project “Santuarios Gestion Desmadres” at the storefront of Cuchifritos Gallery, a program space of Artists Alliance. Together, the two displays shed light on the lived reality and the resilience of immigrants.

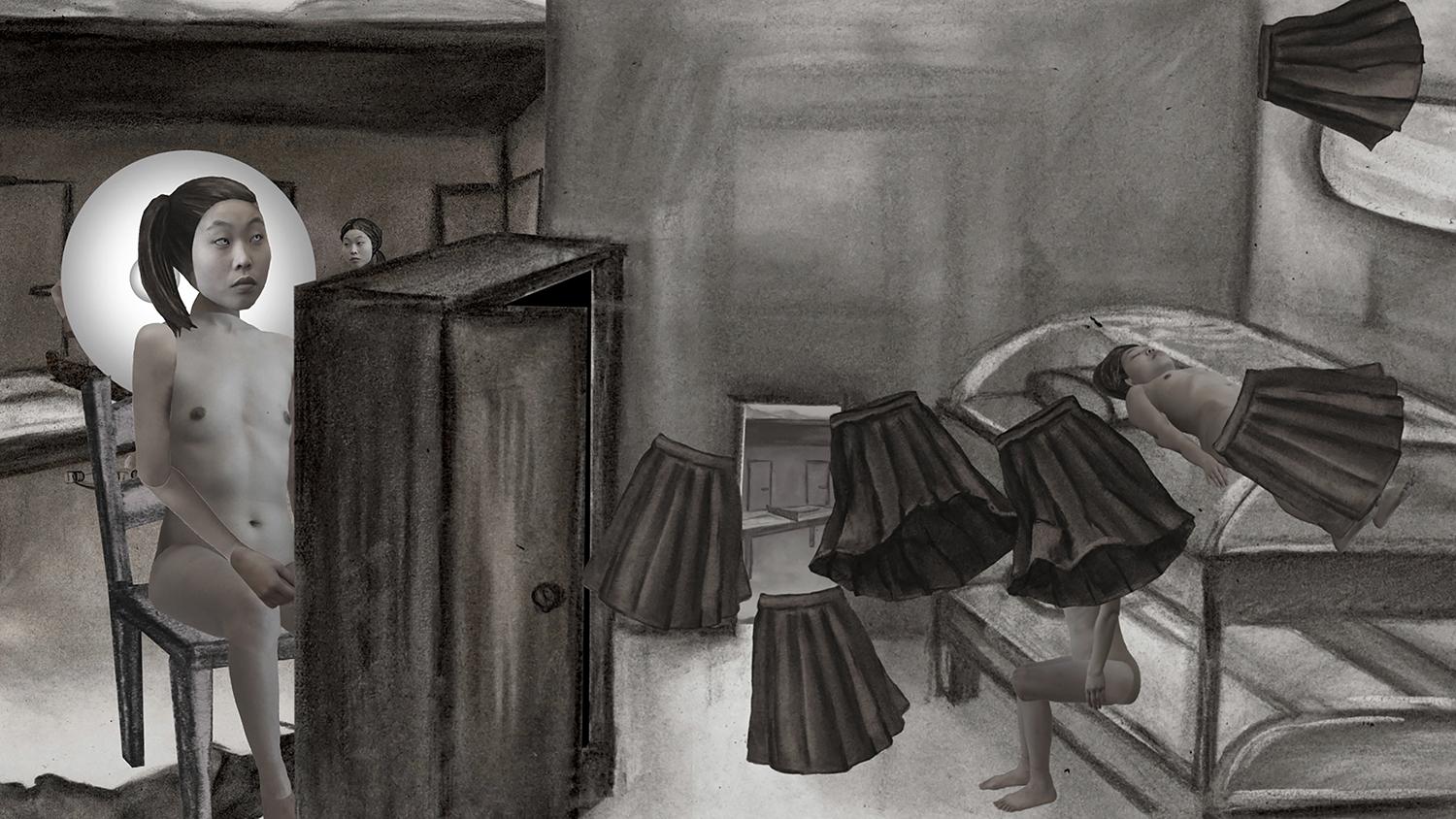

In “Disgraceful Blue” (2016), a woman bears a daughter with blue eyes in her dreams; an attempt to “hide her otherness” has failed as a new generation emerges. South-Korean-born and Vancouver-based artist Young Joo Lee evokes a solemn, gloomy, and psychologically penetrating aesthetic oftentimes found in 20th-century German paintings like in the work of George Grosz. The copy-and-paste heads, corporeal contortions, and a prevalent visual language of fragmentation together form mythical creatures with multiple faces or with noodle-like limbs that seem to contain vortexes of pixels when in motion. The video is not easy to look at—accompanied by sounds of footsteps, whispers, and rain, the nude or seminude female figures with identical, youthful faces confront the viewer with their vulnerability and profound unhappiness. Sometimes the figures’ mouths would be wide open as if in a state of shock; other times their mouths would be downward-turned, rendering the face an emotionally void tabula rasa. Explicitly expressive as these figures are, they also embody a state of stoicism warranted by a perpetuated state of trauma-endurance. These pathologized and quasi-sexualized bodies traverse through the chilling, oblique interiors and head towards an equally menacing outdoors, with an obsolescent landscape of rivers and mountains. Something about the piece’s poignancy is reminiscent of Inci Eviner’s 2009 video, “Harem,” presented at LACMA as part of “Women Defining Women in Contemporary Art of the Middle East and Beyond”—it’s an artwork that expounds on the non-apparent of storytelling and the coerced self-fashioning of “modern institutional inmates.” Pulling the viewer into a haunted dream, “Disgraceful Blue” highlights the definitive discomfort behind feelings of estrangement.

Anna-Ting Möller explores the fundamental complications of kinship: family relationships and lineage are frequently less than linear or straightforward. Navigating her identity as a Chinese-born adoptee by Swedish parents, Möller fosters living kombucha cultures to expand on versified relationship terms beyond their stable categories. Growing out of the initial entity of a kombucha mother, “S/KIN” twists around and folds onto itself, tapping into a mode of simultaneous presences: “caregiver, offspring, and parasite.” The artist complicates the artificiality of certain modes of kinship, highlighting the transcontinental (therefore migratory) and racial connotations behind certain disruptions or alterations that might occur. This reconsideration of motherhood is reminiscent of Coralina Rodriguez Meyer’s project, “Santuarios Gestion Desmadres,” at Cuchifritos Gallery. In this work, which is also a part of TIAB 2023.

Deeply interested in social activism, Rodriguez Meyer documents the ways in which marginalized communities navigate the intersectional barriers of healthcare attainability. Meyer combines photography, neon, belly casting, and plant motifs in this complex installation which, just like Möller’s project, draws on organic metaphors to comment on motherhood and reproduction. Illuminated by an aura of neon green, the double portrait of a pregnant woman’s body is situated in a haven of plants and next to textured sculptures/belly casts, evoking self-care rituals, preservation, and how fertility finds itself in nature. This work also alludes to the artist’s workshops that support the systemically neglected reproductive rights of LGBTQ+ and BIPOC communities.

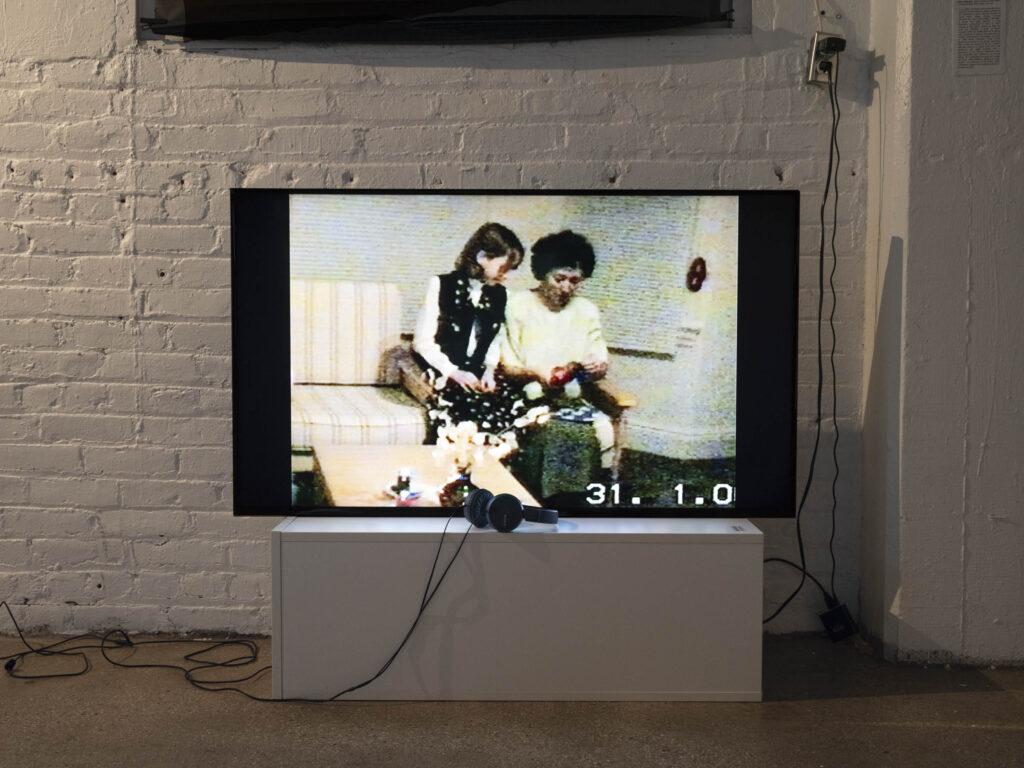

Another case of familial complication is presented by Juna Skënderi’s “Mami Looking at Babi” (2020). It’s a series of videos that are deeply touching because of exactly how unstaged and spontaneous they are. The artist’s mother not only acknowledges the camera, and the man behind it, but also responds to it by smiling or self-consciously glancing at the lens ever-so-slightly, bashful. The shakiness of the footage from a handheld camera adds onto the authenticity and veracity of the way of life that this video seeks to preserve. It’s essentially a pre-Instagram version of a highlight reel, when filming videos would be reserved as a special activity for events like holidays or celebrations. It is this happiness, juxtaposed with the knowledge that this familial harmony would be jeopardized and essentially compromised by immigration, that becomes so powerful in showing just how power structures have destructive powers and frequently disappoint those seeking shelter in this engine.

Alexander Si’s work presents a counterfeit Hermès Birkin in the making; the end result is displayed next to the screen showing the video in which the artist spends 72 hours fabricating the bag. With the bag being literally placed on a pedestal, “Birkin_35” not only comments on the perceived legitimacy that comes with luxury branding and commodity fetish, but it is also a witty twist on the art historical assisted readymade. The artist’s hands practically reverse engineered a merchandise, opening up a pathway onto the behind-the-scenes, “comparing the glamorized labor of craftspeople employed by Hermès to the local crafts and repair industry, as well as the replica trade run by African and Chinese immigrants.” The laborers’ anonymity becomes a major point of contention in this chain of commerce. One is left questioning the conceits behind the ecosystem of luxury that almost declares the supremacy of goods over people.

Throughout the show, we see a subtext of self-minimization out of one’s shame about one’s country of origin or immigration status, shame about one’s ability to identify with a certain regime—be it a regime of luxury, privilege, or nationhood. But is it even fair that immigrants are subjected to these situations? Seeing the graphite grayness in Lee’s work, the round bellies in Meyer’s photography, the time stamps in Skënderi’s video, the savoir faire of Si’s fabrication, and the unconventional living medium of Möller’s sculpture, one is reminded of how, in this messy aftermath of globalization and transmigration, we are left dealing with feelings of fundamental disposability—not due to material overabundance but due to the perils of historical legacies and institutional neglect. Considering “Parasites and Vessels” alongside Rodriguez Meyer’s project, we see how themes of reproductive justice, lineage, familial ties, and labor come together under the overarching concerns of TIAB’s 2023 edition: the reality of immigrant lives and the resilience found in diasporic experiences.

Parasites and Vessels is on view at Accent Sisters until November 19, 2023 and Coralina Rodriguez Meyer: Santuarios Gestion Desmadres is on view at Cuchifritos Gallery’s street-facing windows along Norfolk Street until November 18, 2023.

Art Spiel and Cultbytes are, for the second time, proud media sponsors of the biennial, and this review series is published as part of TIAB’s writer’s residency generously supported by Lesley Bodzy Studio and Fraser Birrell Grier, Esq.

You Might Also Like

Water-bound Semiotics of Displacement and Refuge

Art as an Act of Hope: The Ukrainian Pavilion in Venice and Artists in Flux

What's Your Reaction?

Xuezhu Jenny Wang is a multilingual translator and content creator. In addition to writing about postwar and contemporary visual culture, she is working on a research project that focuses on mid-century interior design and mechanization.