Interview with Warren Neidich About Wet Conceptualism

Adrian Piper’s Catalysis III, in which the artist walked around New York City wearing a shirt emblazoned with the words ‘wet paint’ helped push artist Warren Neidich to moisten the age-old term Conceptualism. Piper along with Yoko Ono, Mary Kelly, Martha Rosler, and Judy Chicago had to await the crisis in social, political, and cultural conditions that the rise of the information and knowledge economy provoked for their exploits to be appreciated as part of the conceptual genre. Significantly, the importance of immaterial objects was superseded by immaterial labor which was performative.

Neidich launched Wet Conceptualism by announcing a hypothetical exhibition in a quarter-page ad in the 50th-anniversary issue of Artforum. Since a URL was required in the ad, he created a website and posted a definition and details about an as-of-yet unplanned exhibition, billing it as “under construction.” Continuing to narrow down his redefinition through writing and conversations he found other artists whose works were, like his own colorful, emotional, performative, and political and therefore excluded from the Conceptualism mindset. He visited the curator and art historian Sozita Goudouna at The Opening Gallery, a new Kunsthalle and non-profit that had just opened in Tribeca to ask if he could curate an exhibition there to materialize the concept, and she agreed. What had been hypothetical became reality and the exhibition Wet Conceptualism took place in December of 2022.

In 1999, Neidich curated the exhibition Conceptual Art as a Neurobiological Praxis, at the Thread Waxing Space in New York City. Then as now, many of the works in the show did not fit within the scheme originally described in the mid-1960s as conceptual art with its non-representational, text-based character, anti-formalist, unemotional aesthetics, and reliance on immateriality. Wet Conceptualism served as a response to his own frustrations concerning his own work which he always had felt was conceptual, but which was not appreciated as such. With the expansion of the age-old term, Neidich’s work, and many other deserving artists can be understood in a larger but more precise sense of the term.

It takes wits, courage, and audacity to propose to the academy that one of its categories, Conceptualism, has perhaps over time become inadequate as a placeholder for work from an ever-broadening, increasingly more democratic group of artist contributors. Over conversations at the gallery, the Harvard Club, and around town I came to better understand Wet Conceptualism (—as well as its counterpoint Dry Conceptualism). Neidich’s argument is intriguing, well-presented, and sound. I commend it to you here.

GR: Warren, your exhibition at The Opening Gallery in Tribeca opened on December 13, 2023. Who were the artist chosen for this inaugural exhibition? On what premise or premises did you make your choices.

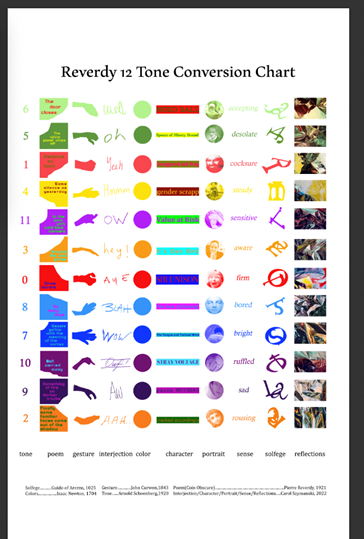

WN: Well first of all although I conceived of the idea of Wet Conceptualism in 2019 it was only with the help of Sozita Goudouna at The Opening Gallery was it able to come to fruition. The conceptual framework of the exhibition was in accordance with the mission of this new nonprofit space that is like a Kunsthalle for Tribeca We had a large pool of artists who we felt would illustrate what Wet Conceptualism was in the past and what it is today. Many of the artists were not available. We did manage to find the following works for exhibition: Sequential Shift, 2022 by Coleman Collins; Frequency Hopping #2, 2019 by Constance DeJong; Articles 2 & 3 from the 1986, Pinkerton’s Agency Man, 1989 by Jimmie Durham; Landscape: Assorted Trees with Regressions, 1981, by Charles Gaines; Untitled (Dreambook or Axis of the Ellipse), 2019 by Leslie Hewitt; Post Fordite, 2020 by Agnieszka Kurant; Shoes, 2020 by Olu Oguibe; Cone Diagram (diptych), 2011 by Jimmy Raskin 2011; Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975 by Martha Rosler; Untitled, 1978-2014 by Allen Ruppersberg; Three Dakini Mirrors, 2021 by Chrysanne Stathacos; and Revery 12 Tone Conversion Chart, 2022 by Carol Szymanski.

GR: I really liked Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen. Could you briefly break down its “Wet” characteristics for me.

WN: Sure. Semiotics of the Kitchen is the perfect Wet Conceptual work. The cooking video spoof was a parody of the Julia Childs’ cooking show airing at that time. Staged in a mundane kitchen with the apparatuses of cooking displayed in front of her, Rosler picks up each instrument in order to demonstrate their use but does so in a transgressive and dubious manner that throws up the entire lexicon of woman’s work into disarray suffused with anger and aggression. She stabs at the air in the imaginary space of ideology and patriarchy that binds woman to unpaid labor. Wet, wet, and wet. To preserve its televisual authenticity, we played this six-minute and nine-second video on the original CRT monitor it was played on in 1975. Of course, its title, which includes the word semiotics, places it in the milieu of indexical works which are the bread and butter of Dry Conceptualism. But that is where the similarity ends.

GR: Were there artists that you would have also shown had they been available.

WN: Funny you should ask. There were many artists and art works that were not available for a number of reasons. Certain works were unavailable because they were already in other exhibitions, or they were owned by collectors who do not lend. Some galleries would not lend out a work because The Opening Gallery was new and had not had the time to develop a relationship with them. The insurance required to underwrite some of the works was astronomical and so precluded their inclusion. Some of the artists we would have like to have shown but could not were Judy Chicago, Felix Gonzales-Torres, Mary Kelly, Adrian Piper and Bas Jan Ader. It was as if an invisible exhibition existed in a virtual space right beside our own. Maybe one day the exhibition can be scaled up and expanded.

GR: That’s quite a list you did manage to exhibit. You made up the term Dry Conceptualism. Why call what has always been considered “regular” conceptual art, dry conceptualism? How does it relate to the theme of your exhibition Wet Conceptualism. Maybe you could define your terms.

WN: For me, dryness describes that form of conceptual art that first comes to mind when one thinks about conceptual art. That is the conceptual art originally described in Lucy Lippard’s and John Chandler’s The Dematerialization of Art (1968) and later delineated in her follow-up anthology published in 1972, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object From 1966 to 1972.

“Dry” is a term that has a tongue-in-cheek aspect to it. Think “dry wit” and “dry humor.” It takes the stoics approach which considers emotions as unreliable idiosyncratic forms of information. Artists like Sol Lewitt are famous for suggesting that emotions were impediments to a mentally engaged spectator and the conceptual artist would like the work of art to be “dry.” Some have suggested that its nihilistic aesthetic conditions or its anti-aesthetic roots were initiated even earlier in the works of Marcel Duchamp, especially his ‘readymades”.

GR: Some have remarked that in conceptual art the idea is of great importance. What is role of the idea in Wet Conceptualism?

Wn; In Dry Conceptual art and Wet Conceptual art, the idea is paramount. Intellectual distinctions take precedence over representational ones. For early Dry Conceptual art is indexical and text based. Works of art are disembodied and unemotional while in Wet Conceptual art, which appeared slightly later, text was embodied, poetic, performative and colorful. Mary Kelly’s early work was a critique of conceptual art. She famously said the personal is political. Her feminist critique and influence were to bring the emotions and the imprecise quality of feelings into conceptual art. As she stated in her National Gallery of Art Talks in 2002 the analytic (dry) proposition of Kosuth needs to shift to a synthetic (flowing) mode which examines and interrogates the messiness of life itself.

GR: How does the notion of language and semiotics inform the distinction you make between Wet and Dry Conceptualism.

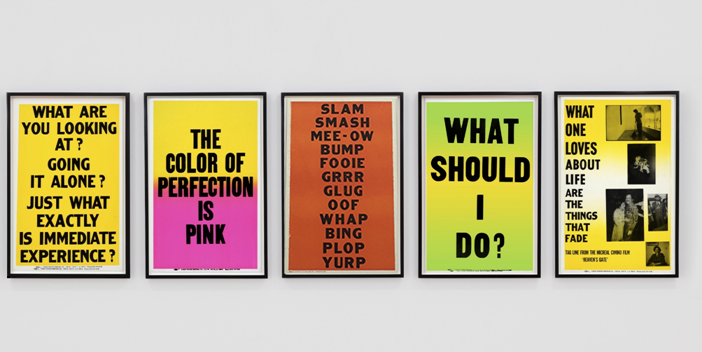

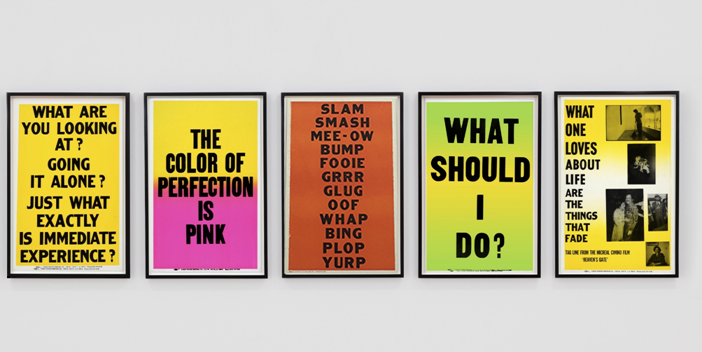

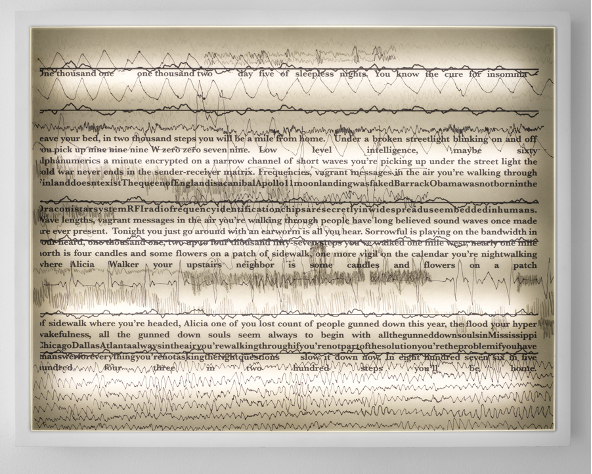

WN: I use the word “language” because language and discourse are essential components of dry conceptual art as a means to eclipse a work’s visuality. But it was also an important component of wet conceptual art. Words appear as the subject matter of Dry Conceptual artworks, but their presentation and meaning are dry, white letters on a black background, taking on the cerebral and authoritative appearance one finds in a dictionary definition. Joseph Kosuth’s Titled [Art as Idea (as Idea)] [SquareWet] (1968) and his Titled [Art as Idea (as Idea)] The Word Definition (1966–1968) are some examples of this. The idea of Wet Conceptualism was also inspired by the text-based work of Adrian Piper’s Catalysis III, in which the artist walked around New York City confronting the public wearing a shirt emblazoned with the words ‘wet paint.’ Ruppersberg’s five polychromatic posters presented in this exhibition and John Giorno’s exotic word work Big Bunch of One Thousand Red Roses (2007) not presented there, are other examples of Wet Conceptualism.

The importance of the poetic voice in Wet Conceptualism cannot be overemphasized as we saw already in Giorno’s work. This voice is also important for Szymanski and Raskin both included in this show. Szymansky’s Revery 12 Tone Conversion Chart (2022) deconstructs the conceptual apparatus of the chart an important trope in conceptual art to mine the poetry of Pierre Reverdy, in creating a twelve-tone interjection series. Notable is Szymanski’s interest in music, sound and language in this polychromic and polyphonic work.

GR: Could you describe some more distinguishing characteristics between Wet and Dry Conceptualism? You said that Marcel Duchamp was a key figure in the history of Dry Conceptualism. Could you elaborate? Did Wet Conceptualism have its own important figures.

WN: Wet Conceptualism defies three key elements of Dry Conceptualism. I might add that it was necessary for me to create the designation of Dry Conceptualism in order to compare it to Wet Conceptualism. Dry Conceptualism was indebted to the work of Marcel Duchamp. When you choose a particular object to become a ‘readymade,” there is the idea that this choice was not an aestheticized decision but a neutral and indifferent one—or dry. An ordinary object could be chosen by what he famously stated was based on visual indifference and only after could it be elevated to the dignity of a work of art That was a key element of dry conceptualism—neutrality as a conscious decision in which no aesthetical judgement took place. You chose objects as “readymades” that entirely lacked aesthetical value. Other Dry Conceptual precedents were Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1913) and the Letterist works of Isidore Isou. Wet conceptualism finds its beginning in other sources such as Francis Picabia, especially The Cacodylic Eye (1921), Antonin Artaud’s shocking Theater of Cruelty (1931–36), the soft sculptures of Meret Oppenheim, especially Object (1936). Wet conceptualism is not neutral in the political sense as was Dry Conceptualism. Olu Oguibe’s, Shoes (2020) is a case in point. Dirty worn sneakers worn by an immigrant in his journey northward to cross the United States border in order to find a better life are exhibited as they were originally found.

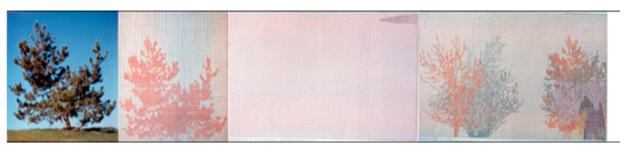

Many of its works are feminist, anti-racist, and post-human. Such as Rosler’s feminist work Kitchen Semiotics (1976), as mentioned, and, not included in the show, Kelly’s Post Partum Document (1973-1979) and Valie Export’s Tapp und Tastkino [Tap and Touch Cinema] (1968). Other examples of political Wet Conceptual works included in the exhibition challenge the Western canon of the Enlightenment. Enlightenment. Gaines, beautiful and colorful work Landscape: Assorted Trees with Regressions (1981) for instance rather than using the Euclidean polyhedral forms for his gridded work he uses instead the topological form a polymorphous tree. The surprising contingent event-related staged photographs of Hewitt’s Untitled (Dreambook or Axis of the Ellipse) (2019) reinvigorate abstraction from its historical relation to static gestalt principles to that of performative affordances characterized by multimodal knowledge and

metacognitive reflection. Although not in our show Pope L. intervention on the work of Gordon Matta Clark Impossible Failures (2023) and Lauren Halsey’s Son of Watts (2022) both exhibited recently in New York at David Zwirner and David Kordansky respectively are also cases in point.

The second element deals with its anti-retinal stance. In Duchamp’s conversations with Pierre Carbanne, it was suggested that what was important about his work and became imperative for conceptual art in general in opposition to stupid painting, was its anti-retinality. It is not work about sensory stimulation. It is not about sensuality. It is about something that happens in the mind, something that happens in what he called ‘the grey matter.’ So, Duchamp wanted to make work that would engage the gray matter. (The grey matter is made up of cerebral cortices cell-bodies, neurons, and glial cells.) On the other hand, Wet Conceptualism understands the wet painterly surface as a place for the evocation of emotions, feelings and affect important in the new economy of social media and Big Data. It is therefore a new site of artistic hermeneutics and interpretation.

This brings us to the third important difference between Dry and Wet Conceptualism. Dry conceptualism is about noesis and idealism, while Wet Conceptualism is about materialism. I would like to suggest that the philosophical trajectory of Dry Conceptualism is enunciated in Plato’s the Allegory of the Cave and continues through to the German Idealism of Kant and Hegel. It then encounters its phenomenological successors such as Husserl and Merleau-Ponty, not to mention Wittgenstein and later the French structuralists.

Wet Conceptualism, with its precedents in materialism’s matter-of-factness and performative knowledge, was initiated by Aristotle and continues with Hume, Nietzsche, Bergson, Deleuze, Stiegler, and Meillassoux. Wet Conceptualism believes in the existence of objects and the time and space they inhabit as independent of human actors and their perception. What Quentin Meillassoux would refer to as being anti-correlational in which thought, and the idea of the world are not always seamlessly entangled. In fact, the world can be thought of as in itself. Acting as composites of living and non-living entities that form active networks operating in the external milieu form performative traces and composites in of themselves that secondarily could sculpt the neural plastic brain.

As such the artistic rendering of them is meaty and material. Both are conditions of mind. The latter would become important in the late days of the 20th century with the advent of cognitive capitalism and in the early 21st century with the advent of object-oriented ontology and specular realism. In the 1960s, as a result of the success of Fordism and industrial capitalism, the world was saturated with objects and Dry Conceptualism was a reaction to this overwhelming condition of material accumulation as well as the importance that the value economy placed on objects, especially art objects. The revolutionary critique of Dry Conceptualism was a reaction to the importance of the immaterial object.

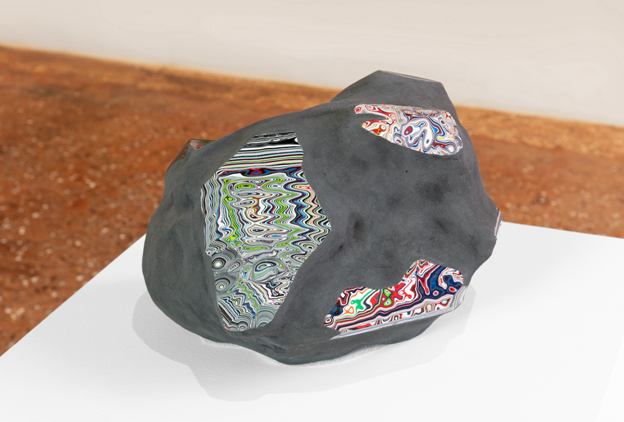

Today we are overwhelmed by immaterial objects of the knowledge and information economy that surround us. According to Maurizio Lazzarato immaterial labor produces the information and cultural content of the art object. Furthermore, as Paolo Virno has stated immaterial labor does not leave a trace. Think here of the labor of a political speech or a music concert. When the audience leaves the concert hall the only thing left is cigarette butts, paper cups, and some other trash. That is not to say that material changes did occur such as those occurring in the the brain as memories or recorded as tweets on Twitter. Recently, the proletariat working on the assembly line of the Fordist factory, using their physical bodies to produce teapots and automobiles has transitioned into the cognitariat working in front of screens using their mental labor to click and swipe what appears on the monitor to create Big Data. Another type of capitalism has been created in the process called cognitive capitalism in which the brain and mind are the new factories of the 21st century. In cognitive capitalism emotions, caring and women’s work have been monetized as we know from the work of Sylvia Federici and as I mentioned before immaterial or performative labor has subsumed material labor. Today we experience this as what is called emotidification in which capitalism targets the emotional well-being of actors. Dry conceptualism as it was conceived and emerged in the 1960’s is not up to the task of resisting cognitive capitalism as another form of conceptualism needs to take its place. A type of conceptualism that had existed all along with Dry Conceptualism, but which was never admitted into its canon. It was only with this crisis of labor that Wet Conceptualism could be realized. Its faint stirrings were already being addressed in the late 1960s and early 1970s as they were conceptualized in the work of Kelly who was critiquing conceptual art as it was known to be. In Kelly’s Post-Partum Document, 1973-1976 the work concentrated on the performative registrations entangled in the mother-child relationship through a Lacanian Psycho-analytic scrim. In this way she brought the feminist critique of women’s work to the forefront of conceptual art practice which I am arguing had no label as yet. Let us not forget that Kelly’s career aspirations were formed in the late 1960s while at Central Saint Martins. It is Kelly’s synthetic sympoietic approach that in the end would provide the conceptual ammunition to resist the despotism of new labor and cognitive capitalism. Agnieszka Kurant’s work Post Fordite (2020) addresses the transition from Fordism to post-Fordism and cognitive capitalism. On one hand, the work is fabricated with semi-precious stones called Fordite or ‘motor agate’ resulting from the build-up of layers of automobile paint found at old automobile factories. She then assembles and embeds them in a matrix of grey epoxy stone in the form of a suspended network or assemblage characteristic of the way information is presented in the new economy.

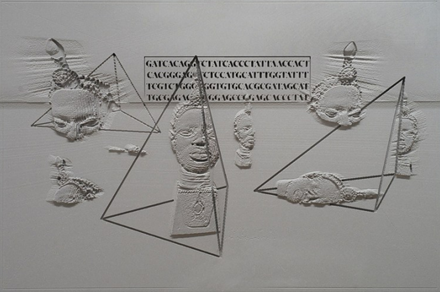

Another work that takes on new labor and cognitive capitalism is Coleman Collins’ Sequential shift (2022). Here the artist is commenting on labor as Duchamp did with his readymade but in this case, industrial production is subsumed by digital labor. The foundation of the CNC-carved piece of MDF is Coleman’s own DNA code, what he refers to as his abstracted self, carved into the surface as a series of base nucleotides. CNC machines use what is called G-code which is generated today using CAM or computer-aided manufacturing. Riffing off Sol Lewitt’s work like Untitled (1982) in which Lewitt used mathematics defined by language, to create his polyhedral shapes Collins presents triangular prismatic structures he calls ideal forms created by digitality. Sequential Shift is a Wet Conceptual work because as its basis it is a work concerned with the history and evolution of material and cultural objects formed outside the Western tradition and an insurgency towards a normative and hegemonic interpretation of forms as they are related to the enlightenment. Instead, they erupt out of an ontogeny of objects based on Ife heads dating from 1100-1500 in West Africa, now Nigeria.

GR: I heard a gallery talk of yours where you mentioned some historical roots of Wet Conceptualism. Could you elaborate them here?

WN: Yes of course. Jane Farver’s Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin 1950s–1980s at the Queens Museum, 1999 was very inspiring for me—that show certainly informed this exhibition. Farver sought to understand conceptual art with an eye toward globalism, and her attempt was eye-opening. Her emphasis on political art was especially important—which for the most part had been left out of dry conceptual art history- beyond its self-reflexive critique of the art process, art world dynamics, and economics. This interest in the global and political in wet conceptual art is portrayed in our exhibition by the work of Cherokee artist Durham’s Articles 2 & 3 from the 1986 – Pinkerton’s Agency Man (1989). The sculpture consists of a wavy red arrowa that leans against the gallery wall and which points to a handwritten sign upon which is scrawled: I SHALL ALWAYS REGARD MYSELF AS A MEMBER OF AN HONARABLE (HONORABLE) Profession, signed Jimmie Durham. He seems to be making a sarcastic textual gesture of which we are unsure of its meaning. Is the profession Durham is writing about the Pinkerton National Detective Agency? A private law enforcement agency famous on the one hand for protecting Abraham Lincoln and on the other for being hired by business (a businessman) such as John D. Rockefeller to kill and intimidate striking miners, or the professional artist working in the art system? The miners are a stand-in of other colonized people beaten and killed into submission by policing forces and the United States Army in the case of the Wounded Knee massacre. His scrawled text is in opposition to those signs and text works normally made by Dry Conceptualists which are usually mechanically produced. His use of a wobbly arrow in this diagrammatic work symbolizes the arrow of the bow and arrow stained with red Native American blood, which was no match in the end for settler guns.

Wet Concptualism’s arts global reach, connection to feminism, and alternate states of consciousness is also materialized in Chrysanne Stathacos’ beautiful mandalas in which she combines feminism, Greek mythology, Eastern spirituality, and Tibetan Buddhism. The work held a central and forward position in the show acting as hub and a greeting.

Another interesting predecessor to Wet Conceptualism was Jörg Heiser’s 2007 exhibition at the Kunsthalle Nürnberg, Romantic Conceptualism. Taking as a starting point Boris Groys’ 1979 essay “Moscow Romantic Conceptualism,” Heiser considered the connection between certain conceptual artworks and the German Romantic period of the 19th century with its emphasis on emotion and melancholia. He referenced works by Bas Jan Ader. In his 16mm film, I’m Too Sad to Tell You (1971) the artist is weeping inconsolably throughout. Along with this work Heiser and team also draw a link between it and Andy Warhol’s 1963 film, Kiss. Jan Aders’s Farewell to Faraway Friends (1971) is a photograph of the artist silhouetted against the orange glow of a beautiful sunset. It takes this connection to Romanticism one step further—directly referencing Caspar David Freidrich’s ruckenfigur images such as The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818).

Romantic Conceptualism was a historically based reframing of conceptualism. The exhibition did not understand conceptualism, as mine does, as a contemporary response to a crisis of labor. Nor did it consider conceptualism as a cognitive revisionist account of the knowledge-based economy that produced it.

Sabeth Buchmann’s essay, “Under the Sign of Labor,” served as an important compass as well as a justification for my understanding of the importance of immaterial labor as the impetus for a new kind of conceptualism. Buchmann’s interest in the work of Lazzarato, who contributed to my book, Cognitive Architecture: From Biopolitics to Noopolitics, 2010, dovetailed with my interest in updating the understanding of conceptual art to expose the aporias of dry conceptualism. Raskin’s Cone Diagram (diptych) (2011) are elaborate productions through which his modes of expression can be materialized as art works in themselves. At 19 he stopped writing poetry to dedicate himself to exploring the conditions of what he calls the poem. His writings, sculptures and props are used in elaborative performative gestures as staged events.

GR: How do these two early forms of conceptualism, dry and wet, as you have organized them as two forceful streams march into the future? Does Wet Conceptualism evolve into post- or neo-conceptualism? Are they the same or different?

WN: Very few people were making the distinction between post- and neo-conceptualism. I am indebted to Alex Alberro’s book, Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity, for his insights about Seth Siegelaub. Siegelaub stands apart as a transitional figure because he conjures a post-conceptual conceptualism based upon immaterial labor and a valorization economy not on the immaterial object. In other words, he reminds us of the importance of immaterial labor as one of the fundamental characteristics of conceptual art. (Of course, there was no category of Wet Conceptual art at that time although he would participate in it unknowingly.)

Siegelaub understood the importance of immaterial labor, labor that does not leave a trace. Think here of what I already mentioned about immaterial labor. I used the example of a politician giving a speech at a political rally or a musician performing at an outdoor concert. But just as easily I could mention the conceptual performances of Tino Sehgal’s Kiss (2002) or The Situation (2007). After the audience leaves, all that is left are cigarette butts and plastic cups. Material labor, like that done in a Fordist factory, produces objects and things like cars and teapots. The economy of his day had gone through a spasm moving away from industrial labor which produced objects into an immaterial labor phase inspired by cybernetics and the service and knowledge economies. Siegelaub either consciously or unconsciously was one of the first to understand this actual, transitional shift. His The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement made with lawyer Robert Projanksy in 1970 was an intervention that questioned making, ownership, display, distribution, and sale of art. Siegelaub scheduled meetings with artists and other art dealers to explain how the agreement worked and as such was a form of performative art that codified immaterial works of art that did not leave a trace as well as acting as a relay point for the history of the institutional critique. Those that predated him, for example, the work of Daniel Buren and Hans Haacke and those which would post-date him like the work Andrea Fraser and Renee Green. To get back to your question post-conceptualism was made up of qualities of both Wet and Dry Conceptualism. What’s interesting about wet conceptualism is that it already existed when dry conceptualism occurred, it just wasn’t allowed to bloom. It wasn’t allowed to be recognized but it operated as an important unconscious influence. I want to suggest that it had an important invisible presence. It was an uncategory. It was sublime.

GR: And how about Neo-conceptualism? Where did that fit in.

WN: Neo-conceptualism is an anathema to both Wet and Dry Conceptualism. Neo-conceptualism is a negative reaction to Conceptualism in general and leads to its demise. It was a product of its times and embodied the social-political-economic relations of Thatcherism and Reganism. The supposed free economy and neo-liberalism.

Neo-conceptualism is radically different from dry conceptualism and is its antithesis. It was a wolf wearing sheep’s clothes and put a stake in the heart or should I say brain of conceptual art. It is what I am calling consumer conceptualism in which artists of the 1980s using techniques borrowed from advertising and media began creatively monetizing conceptual art. Richard Prince’s Untitled (1994) is a case in point. In my opinion, if anything led to the end of conceptualism, it was consumer conceptualism. Today American museums are filled with these hyper-inflated works which have accrued huge value for their collections.

GR: Thank you, Warren. Let us leave it there.

WN: Thank you, Gary.

The fourth edition of Warren Neidich’s Glossary of Cognitive Activism (which includes both the Wet and Dry term) is forthcoming in February 2024 published by Eris Press in collaboration with Columbia University Press. Pre-order it here.

You Might Also Like

Terms of Engagement: Quality, Art-Worlding, and How Performativities Work, Part I

Nikita Gale Loosens Attitudes Around Sound With Her Performa 2023 Commission

What's Your Reaction?

From Mississippi, Gary Ryan is a writer, poet, and chaplain based in Brooklyn. He studied philosophy at Ole Miss and practical theology at Harvard. Ryan has contributed to the Associated Press and writes art criticism for White Hot. In addition, he has represented the Archbishop of Canterbury at the United Nations and taught chess in NYC’s inner city.