Maureen O’Leary Addresses Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising at NYU’s Kimmel Windows Gallery

In 1916, a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a revolutionary group, organized Ireland’s Easter Rising—an armed insurrection against Ireland’s British government that took place during Easter Week. Though the rebellion ended with the rebel forces’ surrender, it’s widely recognized as marking a turning point in Ireland’s pathway towards independence. In a new installation in NYU’s Kimmel Windows Gallery, Maureen O’Leary’s “Portraits of Ireland’s Easter Rising Leaders” pays tribute to the historical event and the members of IRB responsible for it.

A space for “dynamic public art,” the Kimmel Windows have featured a variety of exhibitions highlighting social justice issues, such as “Faces Change | Immigrant Prejudice Remains”— a photography installation that highlights artists “currently documenting the liminal, precarious, and life-threatening experience of crossing the Mexican-American border.” The exhibition is organized in collaboration with Glucksman Ireland House, NYU’s center for the study of Ireland and its diaspora.

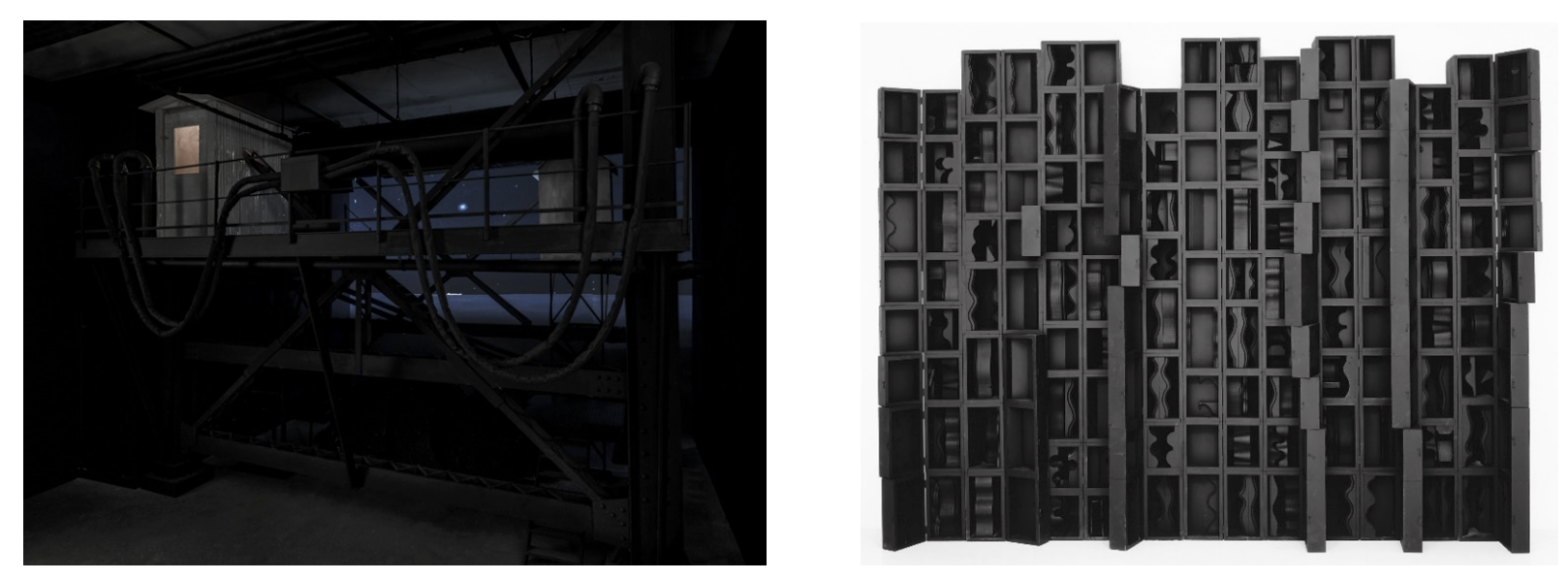

In “Portraits of Ireland’s Easter Rising Leaders,” Maureen O’Leary’s portraits hang like iridescent bubbles of memory over a three-dimensional set, created by artist and theater designer David L. Arsenault to represent Dublin in the rubble of the uprising. Yet the lack of distinctive landmarks gives the setting a universal quality, mirroring the argument of The Irish Revolution: A Global History, a part of The Gluckman Irish Diaspora Series, that frames the revolution as “an inherently transnational event.” As one historian instructs, “No America, No New York, No Easter Rising. Simple as that.”

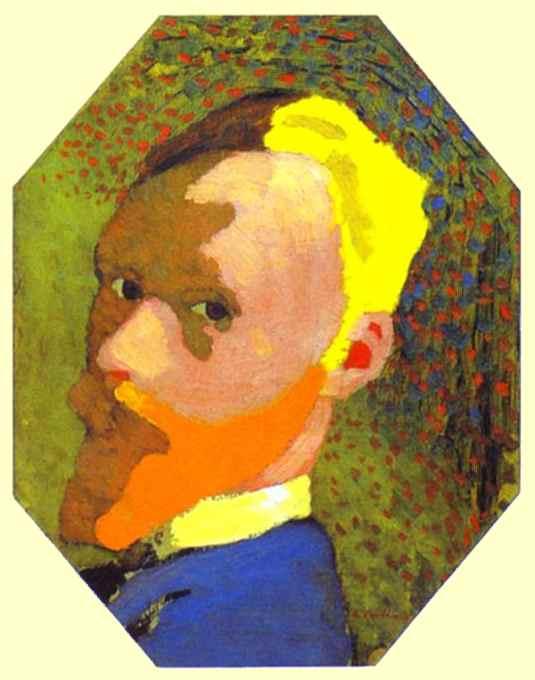

O’Leary describes her colors as “garish,” drawing inspiration from a 1891 self-portrait by French artist Edouarde Vuillard, where his face is depicted in highly pigmented blocks. O’Leary takes a similar approach in depicting the Irish leaders, making visible the act of translation as she imagines and selects colors for each subject—a way to process a personal history through the representation of figures within a collective one. Painted from historic photographs, the artist’s use of saturated color and loose manner of painting illustrate her departure from realism. This stylized approach mirrors the process of memory: details can become convoluted and open to interpretation, just as with the rendering of historical images from photographs.

Nine of the eighteen painted portraits in the series are on display in these windows, which have been transformed into a site-specific installation. The build and casing around the windows are painted a standard utilitarian black that is common in public urban fixtures like lampposts and guardrails. However, the artist has chosen to extend this color choice into the vitrine, giving the display a sculptural shadow-box quality, not unlike the work of New York sculptors Donna Dennis and Louise Nevelson. Their work plays with architectural forms, occasionally creating the impression of life-sized shadow boxes.

O’Leary is both a New Yorker and a first-generation immigrant from Ireland. She is privileged to have access to her individual cultural history. For many, circumstances surrounding their ancestor’s migration may be forced or involuntary. The erasure of language, inaccessibility to or lack of records, and distance from family members, are just some obstacles that can have an impact on the preservation and passing down of personal histories. With regard to this context, O’Leary has done a poetic job of capturing a pivotal moment for the Irish Diaspora grown and fostered in the city of New York.

The Easter Rising captured the U.S. audience with news stories on the front page of the New York Times for fourteen consecutive days. The U.S. was home to many Irish Americans exiled and immigrants that supported the Irish cause.

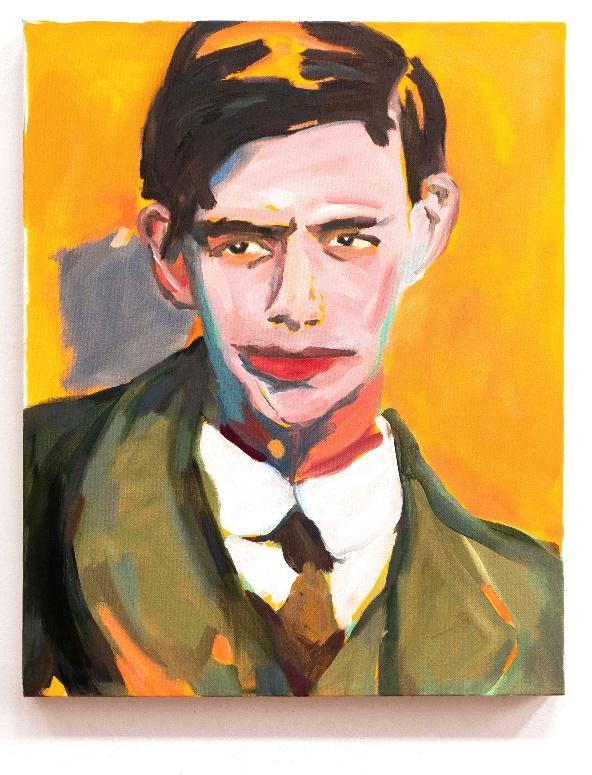

In a portrait of Seán Heuston, O’Leary uses loose brushstrokes and vibrant colors to capture his essence. A rail worker and member of the Irish Volunteers, he is said to have held off three hundred and fifty British soldiers with only twenty-five men for over fifty hours. He was the second youngest person sentenced to execution in the uprising. The colors have a hyperreal quality. They are not as flat as Vuillard’s, almost like the augmented reality of a digital screen. Heuston’s furrowed brow, intense gaze, and narrow shoulders create a feeling of both his youth and dedication to a cause that would ultimately cost him his life.

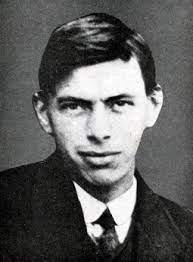

Photographs of Seán Heuston.

Photographs of Seán Heuston.

In instances of collective memory, details can become convoluted and open to interpretation, just as with the rendering of historical images from photographs. O’Leary’s choice to paint the leaders in a loose style mirrors the process of memory. Time passes and we are left to personally illuminate pivotal moments in history from the remnants of the era, examining events from different perspectives and filling in the blanks with our imaginations.

Simultaneously personal and political, O’Leary’s vibrant, evocative works capture the figures behind a significant moment in Ireland’s history. The abstraction of her work represents the creative act of interpreting history, leaving space for the viewer to form their own relationships to the subjects. As O’Leary explains in an interview: ”a painting should not answer all your questions right away, it should let you return to it when you are in different moods and leave room for you to revisit it over years. When I decide to paint something it is because I feel something about it.”

You may also like:

The Immigrant Artist Biennial Offers a Lesson in Perseverance

Can You See the Difference Between Rorschach and Gobolink? Natale Adgnot’s Show Puts You to the Test

“The Art of Making It”: New Documentary Sheds Light on an Ecosystem Failing to Support Artists

What's Your Reaction?

Writer, Cultbytes Kerry da Silva Cox is an interdisciplinary artist, performer, and writer, based Queens, New York. Da Silva Cox has exhibited her work in venues including A.I.R., the Berkeley Museum of Art, and Duke University. Da Silva Cox holds an MFA in Visual Art and an MA in Modern and Contemporary Art Theory and Criticism from SUNY Purchase. She founded the art education and community building platform Big Sky Workshop in 2020. She is a second-generation Brazilian American and a fifth-generation Irish. l igram |