Piecing Together the Stories of Art Lost During 9/11

Yesterday the world commemorated the thousands of lives lost during and after the 9/11 attacks; media outlets broadcasted phone calls passengers aboard the four hijacked planes made to their loved ones, stories of heroic first responders and volunteers saving lives and pulling bodies out of the rubble and those evacuating New York City’s Financial District amidst the chaos. Less reported on is the art lost, described by a spokesperson for the Art Loss Registry as “probably the largest single art loss in history.”

The irony of one of Auguste Rodin’s “The Thinker” being created at the entrance to “Dante’s Gates Of Hell” and itself falling into the fiery hell of 9/11 was a tragedy. The fact it was stolen from the rubble went against the grain of the heroic recovery efforts. Sensational but false headlines appeared after the horrific attacks and soon spread. Most notably, the myth that the financial brokerage firm Cantor Fitzgerald lost a “Museum in the Sky” of Rodins. Widely reported as 300 sculptures, the works lost actually comprised a handful of sculptures and mostly drawings. This inaccuracy is still being perpetuated years later.

The public art losses inspired citizens to help with the recovery, most notably, Alexander Calder fans handed out flyers to recovery workers asking them to be on the lookout for telltale red painted metal fragments of his crushed “Bent Propeller.” 40% of the piece was recovered and is now on display at the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.

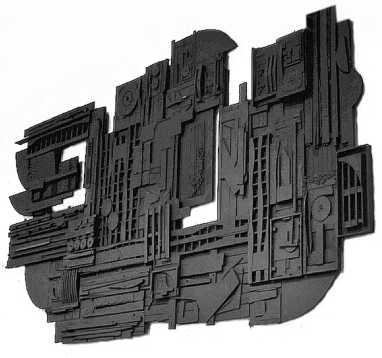

On September 11, 2001 over 250 floors were destroyed in three of the most expensive buildings in Manhattan. The public and lobby art were the most visible pieces to be lost and included work by Joan Miro, Roy Lichtenstein, Al Held, Elyn Zimmerman, Massayuki Nagare, Fritz Koenig, Louise Nevelson, Gloria F. Ross, Cynthia Mailman, James Rosati, and Frank Stella. The Lower Manhattan Cultural Council had taken two floors, 91 and 92, of the North Tower, for art studios and storage. Michael Richards was a sculptor who was in the studios as the plane hit, he died. A retrospective of his work is currently on view at MOCA in Miami. LMCC estimates that 150 works were lost in their “World View” studios by Jeff Konigsburg, Christian Nguyen, Simon Aldridge, Komar & Melamid, Tim Hailand, Daniel Kohn, Taylor Spence, and Takashi Murakami, among others.

In contrast to the victims, in 20 years, this art has never been fully documented or commemorated. In many cases, not even a record or photograph remains. The reasons may be a lack of information, a respect for the human loss, or even the fact that poor decisions were made, such as the theft of the Rodin. The story of how the Rodin sculpture fell into the actual gates of hell – fiery crushed concrete – along with tens of thousands of other works of art is a story that adds to the tragedy of that day.

Because of the complete losses, or reluctance to share information, it has been impossible to collate all the items. In 2002, realizing the importance, The International Foundation For Art Research brought together academics, archivists, researchers and others to try and record the art lost on 9/11 but struggled to create a full list. The proceedings of that conference are the most comprehensive list available. Other organizations such as the Salvage Art Institute attempted to compile a full inventory but without success. Not only the art, but the paperwork to prove much of provenance vanished.

Among the corporations and organizations that held large art collections are the Broadway Theater Archive whose 35,000 historical images of Broadway productions were lost in the attack; works held by Helen Keller International Foundation are still unknown; over 40,000 original photographs and negatives by John F. Kennedy’s personal photographer, Jacques Lowe, were stored in a safe deposit box and did not survive the fire; relocated from Salomon’s offices before the acquisition Citigroup’s dining room had a large mural depicting Wall Street trading and English and American antique furniture, and Asian porcelain that were destroyed. Throughout the building paintings by Carl Schrag, Louis Bouche, John Heilker, William Thon, and a number of paintings by American Realists painted in the 1980’s were among the 1,113 works of art lost.

The Fred Alger Corporate Collection lost more than 45 photo-based works by artists including Cindy Sherman, John Baldessari, Hiroshi Sugimoto, and Bernd & Hilla Becher. Their curator, Leslie Alexander, told ARTnews, “The art, as fantastic as it was, does not compare to the loss of life, even though it makes you sick to think it’s gone…To me it represents a terrible loss of intellect.” Bank of America lost more than 100 contemporary works. In 2001, the corporation’s art program director Becky Hannum stated: “We do plan to tally the amount of loss to our collection.” As of today that list has not become public.

Using the high profile artist names, a figure of $100 million in losses became popularized and the attacks were predicted to cause steep losses to art insurers such as AXA. President of the company Dr. Dietrich von Frank told the Art Newspaper that AXA would accept its losses for the claims of artworks destroyed on 11 September: “I don’t think anybody in their right mind would exclude these kinds of terrorist activities. It is covered,” he said. To the BBC, another spokeswoman from AXA commented: “There will be a global effect on the art insurance industry.”

In Europe, where terrorist acts had occured more frequently than in the US, many insurance companies did not cover losses that resulted from acts of terrorism. But, with the mood at the time, what insurer could be seen to be refusing to pay out? In 2007, JP Morgan Chase paid out a settlement to cover the losses of Jacques Lowe’s archive of negatives and photographs of JFK to his daughter Thomasine, even though they were not legally obliged.

It’s not just about the famous art or corporate collections, artistic objects and valuables in vaults and personal offices were also lost. A vault in Tower Two contained a rare collection of antique rugs valued at over $500,000. These 25 hand-woven kilims had been passed as heirlooms through generations of Muslim families from the Middle East, North Africa, and Southeast Asia. Their owner believed them so secure in their special climate controlled vault that he had not insured them. Much of sentimental value, like art by worker’s children on display in their offices, was also lost. Before the attack, it was art that made the buildings human.

Many federal agencies had their archives at World Trade Center; a box containing artifacts from the African Burial Ground was unearthed beneath the debris but most archives and artifacts were not found. By law these agencies are obliged to report the destruction of records to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration but ten years later none had.

Companies and agencies chose to be based at the World Trade Center because it had literally proved itself bomb proof, so for many there seemed little need to insure artwork. Firms such as Marsh & McLenan were insurers themselves but had not insured their own art collections. Others were so big that they likely forgoed art insurance. The fact is, insured or not, companies thought it rightfully distasteful to talk about the lost art when the human tragedy was far more significant.

There is still time to to piece together the story of the art lost during 9/11. And, raise a toast to the late Milton Glaser who designed the logo which went on everything from the plates to the menu at the infamous Windows on the World restaurant, situated on the 107th floor, to its large picture of Andrea Doria sailing into the harbor below painted by Ronald Mallory, and all works lost.

This article reflects the author’s decade long research into the loss of art but he is the first to admit that he is no curator or art historian, and hopes to inspire others to continue to reveal the art that has remained hidden since that dark day.

What's Your Reaction?

Adrian Wilson is an artist and photographer based in New York. l Instagram l