Quilted Portraits that Evoke the Racialized and Gendered History of Craft

During slavery in America, it was common that African and African-American slave women worked with spinning, weaving, sewing, and quilting on plantations and in wealthy households. Although there was little time remaining in the day some still quilted for their own families using available scraps of fabrics. After the civil war, African-American women continued to work with sewing and quilting as domestic workers. The latest exhibition at Claire Oliver Gallery in Harlem unveils seven colorful quilted life-size portraits by Bisa Butler in which she evokes this racialized, gendered, and political history of quilting.

Six of the seven portraits depict anonymous people from photographs that Butler has sourced from the Farm Security Administration database of black Americans taken between 1937-1942. The figures are brought to life through Butler’s use of vibrantly colored fabrics; Butler uses fabric to convey narratives that rely on their origins. The West African, or Dutch, wax print she uses is industrially produced and associated with celebratory events in West Africa. Kente cloth is a silk and cotton blend fabric that dates back to the Asanti people of Ghana, where her father is from. Each portrait reveals an imagined personal history that dates back to their African heritage.

In the 19th century, the social reformer Frances Willard, most famous for serving as the president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, successfully mobilized members to quilt as a means to express their voice and political agenda. Mothers, daughters, and friends across Northern and Southern America united in sisterhood to fight the country’s excessive use of alcohol using expressive quilts as vessels for change.

Willard allowed the social understanding of quilts to move beyond wearing and domestic use by emblazoning them with political messages and bringing them into the public. Women and feminists have continued to use quilting as an act of defiance. Craftivism, a term coined by Betsey Geer, which includes quilt activism, is a third-wave feminist movement of quilters and crafters who use their practice to take on social causes. “Craftivism is about raising consciousness, creating a better world stitch by stitch,” Greer writes. Butler’s quilts celebrate the craft and skill of the women before her – black slaves, domestic workers, and feminists alike. By merging expensive and inexpensive fabrics, luxurious and durable such as lace and burlaps, she threads together histories to create one story.

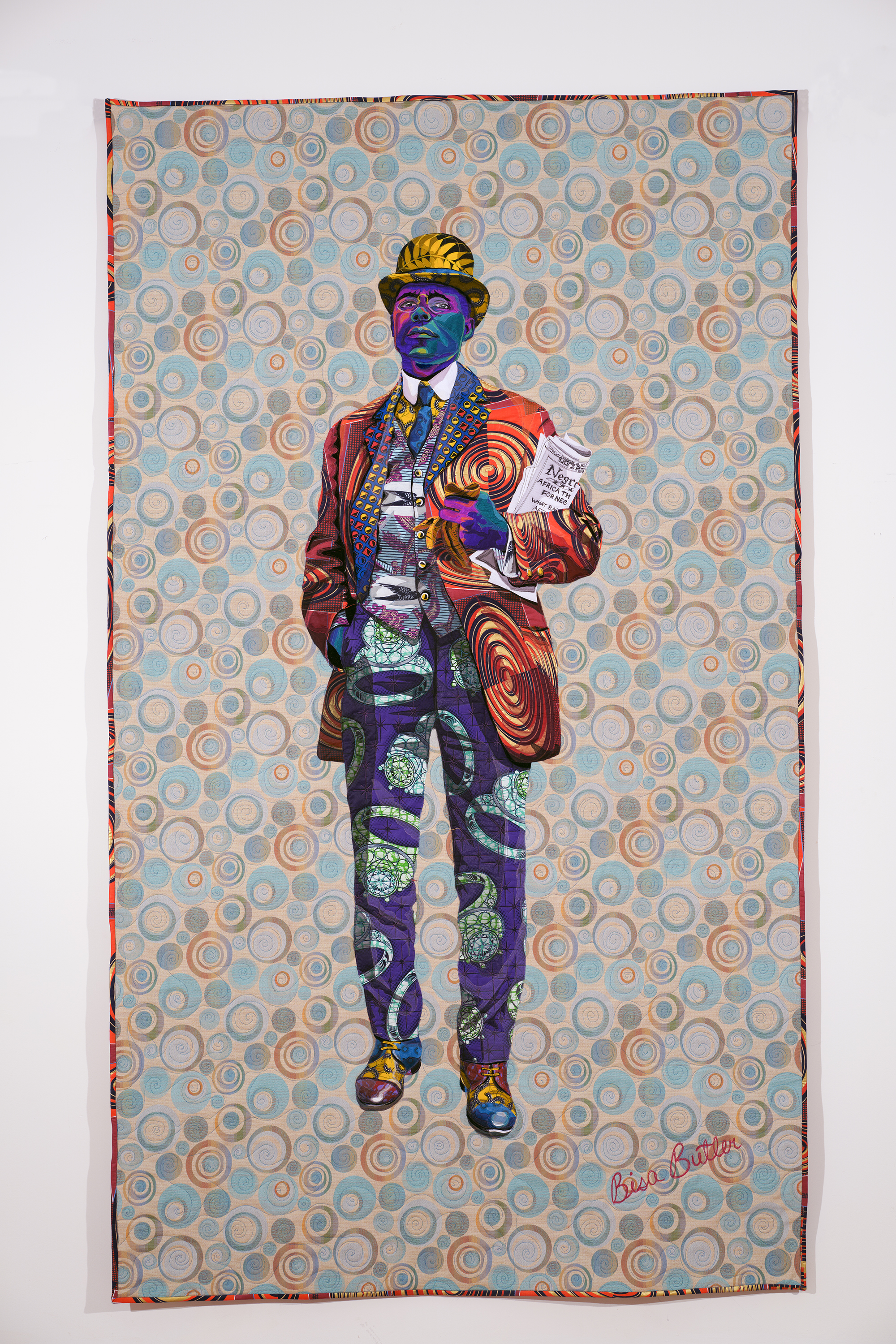

Above: Bisa Butler. Asantewa, 2020. Cotton, silk, wool, and velvet quilted and appliqué. 52 x 88 x 2 in. Previous: Bisa Butler. Africa Land of Hope, 2020. Cotton, silk, wool, and velvet quilted and appliqué. 52 x 88 x 2 in.

Above: Bisa Butler. Asantewa, 2020. Cotton, silk, wool, and velvet quilted and appliqué. 52 x 88 x 2 in. Previous: Bisa Butler. Africa Land of Hope, 2020. Cotton, silk, wool, and velvet quilted and appliqué. 52 x 88 x 2 in.

Outlining diversity of African-American heritage through Technicolor cloth, Butler’s portraits are political as they give voice to unheard stories; the artist depicts each person in her own narrative. Looking at each portrait, I was drawn into an emotionally vulnerable space, one that is accompanied by the warmth and the history of fabrics. In the quilted portrait, “Asantewa,” Butler constructs the facial features with orange, pink, purple, and blue. Each color outlines a separate line and muscle driving every expression in her face. Butler uses contrasting colors as a means to emphasize each emotion. The figure’s hair is in an arrangement with black sheer flowers that crown her head. The patterned fabrics Butler uses to re-create the photograph brings the figure away from their original scenery, thrusting them into something new, the new juxtapositions of material and thread spin a new story.

Working with leading artists in the Africobra movement inspired Butler’s use of bright colors. Africobra often referred to their use of bright colors as “kool-aid” colors which integrated vivid colors and pro-Black subject matter. The use of specific colors like orange, strawberry, cherry, lemon, lime, and grape emit elements of nature and the sun. The artist’s connection to quilting is matrilineal as her knowledge of textiles was passed down from her African grandmother. She transitioned to quilting as a means to protect her daughter from toxic art materials.

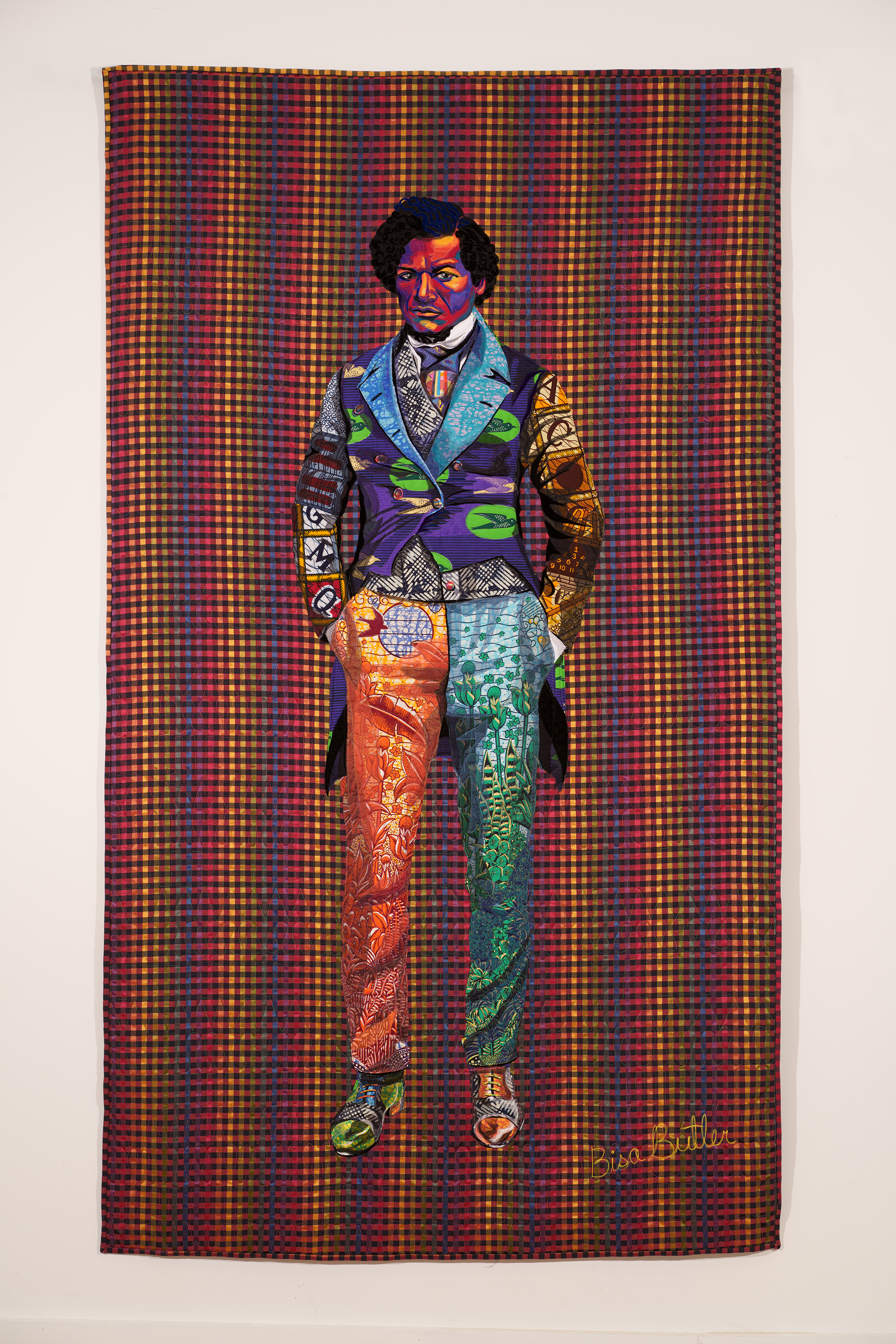

Bisa Butler. The Storm, The Whirlwind, and the Earthquake, 2020. Cotton, silk, wool, and velvet quilted and appliqué. 50 x 88 x 2 in. All images courtesy of Claire Oliver Gallery.

Bisa Butler. The Storm, The Whirlwind, and the Earthquake, 2020. Cotton, silk, wool, and velvet quilted and appliqué. 50 x 88 x 2 in. All images courtesy of Claire Oliver Gallery.

In a speech given on Independence Day in 1852 Fredrick Douglass rebuked slavery, the title of Butler’s exhibition is based on this quote: “It is not light that we need, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake.” In his speech, Douglass supported the ideas of freedom pertaining to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Butler’s only portrait of a person that is named is of Fredrick Douglass.

The exhibition draws a parallel between the hypocrisy of Independence Day during slavery with that of craft and quilting and its lower standing in the hegemonic art world. Looking with a larger timeframe in mind Butler evokes emotions that shift from rejection, abuse, and punishment to optimism, content, and hope.

Today, the relationship between art and craft, or even craft art and fine art is a discussion that continues. However, fiber art has been around for centuries, and has served both functional household and had decorative functions. For instance, ornate and simple carpeting has been used to adorn walls to regulate the temperature in renaissance palazzos and Bedouin tents, across time and societies.

The earliest quilts are traced as far back as 5,500 years. In an ivory carving from Egypt, part of the British Museum’s collection was found in the Temple of Osiris at Abydos and depicts a male wearing a cloak. Quilting rose up in Europe during the 12th century when the Crusaders wore quilted garments. Quilting fabrics were often assembled by what was available; thus the reusing of fabrics and older quilts create a touchable historical lesson that reveals intricate histories of culture, across gender and social class.

I strongly recommend this exhibition in which Butler cleverly decontextualizes her sitters placing them in an overarching multi-layered and intergenerational narrative. The quilted portraits resonate with many while highlighting the universal importance of the craft. Butler takes control of the African-American narrative by closing the gap between craft and fine art. When taking in her collaged visually striking portraits it is as if their existence as wall-covering, functional household items, or artworks dissipates and the presentation of a new honorific narrative remains.

Due to COVID-19, visits to the gallery are by appointment only. Claire Oliver Gallery, 2288 Adam Clayton Powell Jr Blvd, New York, NY 10030.

More by the Writer

Kennedy Yanko Explores Shifting Identity Through Repurposed Metal

The Ins and Outs: Derrick Adams Unravels the Black Narrative of Chicago’s Landscape

What's Your Reaction?

An art professional with Chicago-based art non-profit Project&, Caira Moreira-Brown studied Art History at The Ohio State University receiving a B.A in History of Art with an emphasis on Post-Modern and African-American art history. She regularly writes for FAD Magazine and founded the podcast The Curatorial Blonde. Previously, she has held positions in gallery administration at Fredrich Petzel Gallery, 67 Gallery, Joseph editions and has worked at Kim Heirston Art Advisory and The Wexner Center for The Arts. Moreira-Brown is interested in post-modern race relations and narrative change. l igram l email l