A Guide to Visual Arts, Science, and Climate Change

Last summer the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin held a large scale exhibition of the work of German expressionist painter, printer, and watercolorist Emil Nolde (1867-1956). “Colour is Life,” as the exhibition aptly was titled, contained over 120 watercolors and drawings.

As I wandered through the exhibit in awe I especially admired Nolde’s spectacular oil paintings of the sea: ranging from his depictions of tugboats in Hamburg’s harbour to his colourful portrayal of beaches in New Guinea in 1914 and his paintings of the wild North Sea near his home of Schleswig Holstein near the Danish border in Northern Germany.

My enthusiastic mood instantly grew somber, however, as I read what Nolde had to say about his painting “Light Breaking Through” (1950): ‘The wide tempestuous sea is still in its original state. It is the same today as it was 50,000 years ago.”

If Nolde only knew the pitiful state of our oceans today he would be shocked; that ocean acidification is killing off coral reefs and also that it is projected that there will be more plastic than fish in the oceans by 2050. I reviewed the exhibit in depth but I could not forget how out of date Nolde’s description of the sea has become.

In early October 2018, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change dropped their damning report that the world now has 12 years to cut carbon emissions to give us any hope of keeping average global temperatures below 1.5 degrees to help prevent the worst effects of climate change. As I continued to read the many articles about climate catastrophe that have been published in the past months, I have been questioning my role as an arts and culture reviewer, and indeed, where my priorities should lie in my reviewing. I am, naturally, not the only reviewer or artist to pose this question lately.

Previous: Emile Nolde, “Light Breaking Through,” 1950. Photograph courtesy of the Nolde Stiftung Seebüll. Above: Olafur Eliasson, “Ice Watch,” 2018. Melting block of ice sourced from Greenland. Photograph courtesy of the author.

Previous: Emile Nolde, “Light Breaking Through,” 1950. Photograph courtesy of the Nolde Stiftung Seebüll. Above: Olafur Eliasson, “Ice Watch,” 2018. Melting block of ice sourced from Greenland. Photograph courtesy of the author.

Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson told Dezeen Magazine the following in an interview: “The cultural sector has a very strong relationship with the general civic society and has a mandate to express itself and to voice its concern, when the so-called public sector, the politicians, fail to do so.”

Olafur Eliasson’s recent exhibit at London’s Tate Modern was an attempt to showcase the urgency of climate activism to the public. “Ice Watch” which Eliasson conceived with the help of geologist Minik Rosing, was a group of 24 blocks of ice placed in front of the Tate Modern.

The blocks were fished out of the water in Nuup Kangerlua Fjord in Greenland and shipped to London after becoming detached from the ice sheet. When they were first installed last December 11th (to coincide with the opening of the COP climate conference in Katowice, Poland) each block weighed between 1.5 and 5 tonnes and were on display until they melted.

I visited the Tate Modern in early January and they were still there but melting steadily. You could touch them and smell them, climb on them and consider their meaning. “It is a lot more physical; it suddenly gives a stronger sense of what it is scientists are talking about when they say the Greenland ice caps are melting,” Eliasson says.

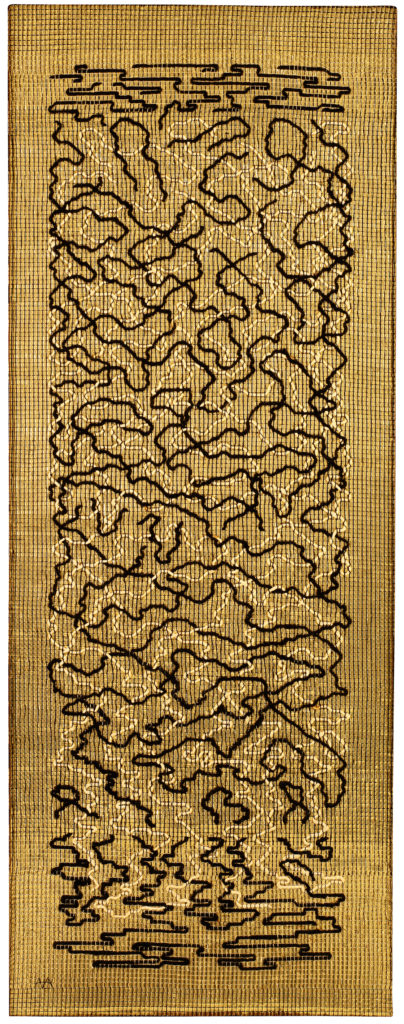

Anni Albers, “Epitaph,” 1968. Pictorial weaving, 1498 x 584 mm. Photograph courtesy of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation.

Concurrently, in observance of the centennial anniversary of Germany’s Bauhaus School, “Anni Albers” was on view. When Anni Albers (1899-1994) arrived at the Bauhaus she had hoped to pursue painting, when she found out women were not allowed she pursued fiber art. Albers became one of the leading innovators committed to combining the ancient craft of weaving with twentieth-century modernist abstraction.

Much of Albers’ weaving was inspired by the textiles of ancient Peru. She produced a number of works that show her understanding of how important textiles were in serving a communicative purpose as there was no written language. And while I am a writer and am using words to express my anxiety about climate change, the Albers’ exhibit reminded me that there are so many mediums for artists and activists to use to promote dialogue on climate change.

Joan Sheldon, Global Warming Scarf, 2015. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

In 2015, the University of Georgia marine scientist Joan Sheldon used not weaving, but the craft of crocheting to express her concern with global warming. Using the climate data of the day she began crocheting a scarf in different colors to represent temperature changes from 1600 to the present using purple, red and yellow for different temperatures in the earth’s atmosphere. When Sheldon presented her yarn scarf at a conference, scientists paid attention. The popularity of knitting and crocheting climate data into colorful visualizations has exploded in recent years promoting meaningful dialogue on climate activism.

Wolfgang Tillmans, “Red Lake,” 2002. Photograph courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

Wolfgang Tillmans, “Red Lake,” 2002. Photograph courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

As I continue to question my role as a reviewer in a time of climate crisis I find myself actively seeking both the climate metaphor and message in whatever artform I review whether it be painting, photography, music or literature.

The IMMA (Irish Museum of Modern Art) in Dublin recently exhibited over 100 works by renowned German photographer Wolfgang Tillmans. The exhibit did not focus on one genre of photography but rather encompassed a whole spectrum of his work in all sizes and also included a sound installation.

The IMMA catalog on the exhibit states the following: “This physical layout, a sense of interconnectedness and immersiveness that is provoked by being surrounded by images suggests that so many seemingly disconnected subjects, movements and people are, in fact, connected by larger forces at work in the world: political and economic structures, pop culture, consumerism, cheap and available travel, technological advancements and more.”

Tillman’s exhibit served as an open question for the audience to interpret. As I moved through the exhibit soaking up Tillmans’ many ideas, two photos, in particular, caught my eye. One was “Red Lake” which left me pondering the environment. The red water looked like blood which reminded me of how climate change is slaughtering the natural world. Another was a large photo of a cardboard box filled with pill and medicine bottles and was titled: “17 year supply.” I immediately thought of climate doomsday scenarios and hoarding of food and medicines to enable us to live through the effects of monster hurricanes and droughts, but of course, we know too little about any serious timeframe for climate tragedy to begin hoarding.

It is not my intention to map out specific implications, indeed, it is impossible to do so, when what we face is a complex predicament beyond our control.

-Jem Bendell, Professor and Climate Change Activist

Jem Bendell, who is a professor of sustainability leadership and the founding director of the Institute for Leadership and Sustainability at the U.K.’s University of Cumbria believes we face near term social collapse due to climate change but he is also not being explicit as to when exactly because how can we possibly be so with something as global as climate change? He writes: “It is not my intention to map out specific implications, indeed, it is impossible to do so, when what we face is a complex predicament beyond our control.”

His roadmap for navigating climate tragedy is more a framework of ideas and points to help up prepare spiritually and psychologically for inevitable climate chaos that lies ahead. He calls his plan “Deep Adaptation” and it involves a three-step plan of resilience, relinquishment, and restoration. He asks what the valued norms are that human societies will wish to maintain as they seek to survive.

How will we resiliently adapt to changes? What practices or pursuits must we relinquish or give up so as not to exacerbate problems? He mentions withdrawing from coastlines as sea levels rise and closing vulnerable industrial sites. I am reminded of the IMMA catalog about Tillmanns’ that talks of consumerism and cheap and available travel. We most certainly will need to scale back our rampant consumerism, but there is hope, as Bendell writes, of the values, we will wish to restore that have become eroded in our hydrocarbon-fuelled world. He talks of a rewilding of landscapes to provide more ecological benefit, changing diets back to match the seasons and rediscovering non-electronically powered forms of play and entertainment.

While Bendell writes of inevitable near term social collapse and possible human extinction which is enough to terrify anyone, he also says that when he discusses these ideas with his students, apathy, and depression are not the typical reactions but rather, in a supportive environment something positive happens. Students appreciate life more, shed a feeling of needing to conform to the status quo and are more creative and imaginative about what their priorities should be moving forward.

***

I have asked myself: “Why review art when we face imminent ecological and social collapse due to climate change?.” I fully agree with Olafur Eliasson that the cultural sector has a duty to keep the climate change dialogue open in the absence of as yet, serious commitments to carbon emissions reductions on the part of our political leaders and the majority of corporations. But, while we live in a time of political uncertainty, discord and disharmony we are, as Tillmans points out, nonetheless connected by forces larger than us in the world. We have methods of communicating and sharing that are far more sophisticated than weaving and yet, we can draw hope from the beauty and messages that these ancient traditions hold.

***

I look around me and see artists, photographers, musicians, writers, and poets of all ages becoming more and more involved in climate activism. There is hope, after all, to be found in the arts no matter how challenging life becomes and I hope the visual arts will continue to motivate us all to keep on working, collaborating, and raising awareness of the biggest challenge facing humanity.

Related Articles

Survival Kit 9: Exhibiting Radical Solutions for Society’s Survival in Latvia

What's Your Reaction?

Writer, Cultbytes Rhea Boyden is the Irish-born daughter of American parents. After years of studying and working all over the United States and Berlin, Germany, she now lives in Dublin where she reviews, art, music and literature. She was a contributer to Slow Travel Berlin, an arts and culture magazine in Berlin and helped author a Berlin guidebook with the magazine. She has been published in the Irish Times as well as various anthologies. She reviews music in Dublin for PHEVER: TV-Radio and spends a lot of time in art museums pondering life. l igram l