Archive Fever’s Poetics of the Past

At the opening of Archive Fever, people wade through a mist of sound and images as if caught in a commiserating kingdom of the dead. Upon entrance, one is struck by how familiar all of it looks: with clothes hanging from the walls and a television set, the bright, strong colors and oceanic chords of the space are shot through with an apartment’s intimacy. However what exists, sings: installations melt into one another through your ear canals and the corner of your eyes, creating an entirely unique experience that continues to ring within you hours after.

“People often remark that ‘the archive’ as a theme is ubiquitous, even exhausted,” the exhibition’s Yanbin Zhao explained to me at the opening. “I agree to an extent, yet I also feel that this fatigue stems from a superficial engagement: the concept of the archive has expanded, but not always deepened. As a result, we often encounter works that simply exploit archival aesthetics—relying on appropriation, collage, or flicker effects—without critical rigor or specificity.”

The exhibition’s title, Archive Fever, is borrowed from Jacques Derrida’s essay of the same name. The book, which has become a seminal work in archival studies, examines Freud’s oeuvre to argue that the archive is less a fixed repository of memory and more of a turbulent force that voices its desires for the future.

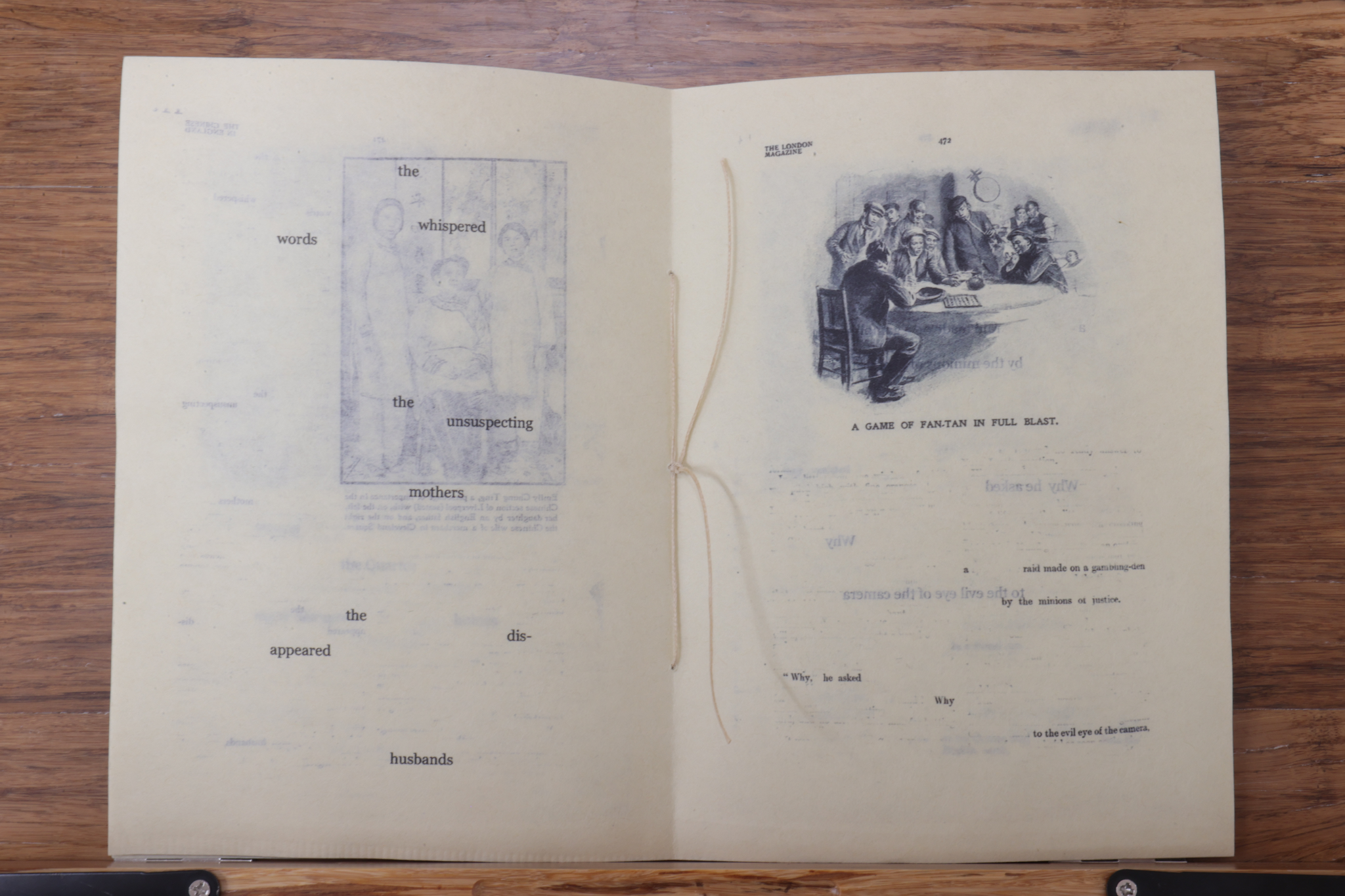

Zhao’s exhibition has a similar conceit. “My interest has remained with artists who approach archival materials in a way that genuinely extend our understanding of what an archive is and can do—artists who complicate, deepen, or reanimate their sources,’” he continued. Then citing Rose Salane’s List Projects and Rabin Mroué’s Pixelated Revolution as initial sources of inspiration, as they exemplified for him “projects that probe what is missing or unrecorded…practices that address the opacity or amnesia inherent in historical preservation.” Indeed, the works featured in Archive Fever include both traditional archives and subversions of the archival form. From her “Erasure Series” collection, Hester Yang applies the modernist tradition of erasure poetry to a 1910 article called “The Chinese in England: A Growing National Problem,” recasting its racist depiction of the Chinese community in Liverpool into a text that foregrounds their experiences of displacement and migration. Jiayue Yu’s “Another Dream” depicts postwar influence on domestic life by displaying found Japanese family archive photographs from the 1950s to 1980s under Showa sheet glass, a special type of glass produced in Japan during the same period. In a similar vein, Matilda Yueyang Peng combines old photos and documents to reveal the invisible effects of the Cultural Revolution on her family in her work “Special Materials.”

Archive Fever also included works that engaged directly with public historical records. Compiling notes, poems, quotes, and personal correspondences into an unbound book in her work “We sit together, opening each to each,” Rita Borich features excerpts from the Mary Wright Plummer papers to craft a holistic picture of Plummer that considers both other perceptions of her and personal accounts. Examining the legal dimensions of a public archive in his photo collection “Fair Use I,” Justin Jinsoo Kim examines copyright laws and their implications for the subjects of these images by rotoscoping stills from a thirty-second newsreel footage. Yuyan Wang echoes this critique of the surveillance state in his video Look on the Brightside, which is set in a nocturnal society that is perpetually irradiated, based on China’s 2018 initiative to launch three artificial moons in orbit to provide continual daylight to major cities.

Other works sought to provide legitimacy to sources that are typically unrecognized as archival sources. In “Waegwan from Above // Hill 303, 1954,” Emma Kang reconstructs her grandmother’s childhood spent under the specter of the Korean War. Inspired by her great-grandparent’s history as Japanese immigrant laborers on sugar cane plantations in Hawaii, Maya Jeffereis creates a video that combines both traditional archival footage and excerpts of Japanese, Carribean, and Pacific poetry to craft a story drawing from both public and private realities. Elizabeth Chang also plays with the different registers of recorded history in “I Heard,” a sound installation that overlays the repeated phrase “I heard” over news channel reportage on U.S. military bids. In “Atmospheric Archive,” Lynne Smith refires window glass and atmospheric residue sourced from the land that now houses the National Building Arts Center, formerly the Sterling Steel Company, to memorialize the environmental destruction and racial discrimination that land overturnment has obscured.

However, Archive Fever also envisions the archive as a site of futurity, potentiality, and care. In her interactive installation “Matrilineal Hair Archive,” Beatrice Mai assembles hair collected from volunteers and asks them to contribute a physical or emotional trait that they’ve inherited from their mother. M. Torres and Eden Kinkaid “Assembling Gender” posits lesbian/gay porn magazines, contemporary art magazines, images from the Internet, and more as rich repositories of gender exploration, for gendered forms already extant and those that are still in the process of becoming. Lastly, Shanzai Lyric features a portion of their poetry garment archive, comprised of shanzai (“copycat”) t-shirts that both reproduce and satirize dominant sartorial symbols of prestige.

Other artists explore the archive in a more existential sense, questioning who creates them and who controls their legacy. In Autopsies, Allie Tsubota draws from an 1870 photograph of Chinese boys who were trafficked from California to New England as strikebreakers, inventing an imagined boy from the photo to create a speculative archive that included sculpture, photographs, and a fictional text. An archivist herself at Columbia University’s C. V. Starr Library, Evian Pan contemplates the purpose of work in a structure made of sheet protectors, plastic filing envelopes, prong fasteners, and discarded binder rings—shedding light on the routine of transferring archives from one package to another, creating empty husks in their wake.

To see these works in conjunction is to corporealize the archive, and to see beyond what can only be flattened into historical remembrance: pictures of loved ones, surveillance stills of strangers. The frail polyester of cheap clothes. News footage as diary entries on public life. All of the world blocked—by words, by glass, by other histories that run nonstop.

Although Zhao has mainly hosted screenings in the past, his talent for curating visual arts exhibit is evident. “Specificity—truly understanding each work—shaped many decisions,” Zhao said. “Lynne Smith suggested installing her piece closer to the floor to emphasize its connection to the earth. Jiayue Yu’s works are positioned beside the windows because they reference a distinctive type of Japanese glass. One of M. Torres & Eden Kinkaid’s pieces is placed directly on the floor to create a transitional sensation that echoes the playfulness within their collage series. These small gestures were important: they allowed the space to respond to the works, rather than the other way around.”

Just as the title “Archive Fever” itself is a contradiction—one can hardly imagine dusty pages engaged in such biological arabesques—the experience of the exhibit itself recalls a Faulkner quote I’ve thought about for many years: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Zhao’s exhibit is a thoughtful reconsideration of the “archive” that articulates a genuinely new perspective on a well-treaded subject, crafting a space that is equally as impactful as the individual works.

Archive Fever is on view at ACCENT SISTERS, 89 5th Ave #702, New York, NY 10002, from November 21st to December 3rd, 2025.

You Might Also Like

What's Your Reaction?

Annelie Hyatt is a writer based in New York City. She graduated from Barnard College with a degree in English and History, and has since been interested in exploring the intersection of the two disciplines in her academic and creative life.