Artist Nives Widauer’s Apartment Where Democracy Dreams and Trees Swim

After a buffet dinner, a group of women lingered in the kitchen, speaking heatedly about democracy—the hostess, artist Nives Widauer, explains that her native Switzerland has the most favorable system, as it is a direct democracy. Although she explains, it might feel politically sedate, it is a system that avoids a lot of power being awarded to one single individual. Disagreement ensued. Having just shipped work to Bucharest’s contemporary art center /SAC to be exhibited in The Thin Thread Line, a group show engaging with democracy and values, it is a theme she has recently dug more deeply into. “Freedom of speech is something people living in democracies take for granted. But the lines are not fixed and things are shifting, sometimes silently and often very fast,” she says. Poetically, she compares the movements to moving sand in the desert, sometimes hard to notice but swift and irreversible. She sees a danger of rising populism, declining democracy, and, popular in many academic decolonial leftist circles, the will to adopt undefined new systems. “How will culture survive in this new system is the question?” she asks. We move to another topic—guests are comfortable with discord and debate. Perhaps the home’s creative vibe encourages it, or it is Viennese; I am not sure.

Widauer is an artist who deconstructs and reconstructs disparate things that many might take for granted, or overlook completely: the sky, bodies of water, ecology, the life and work of classical musicians, or women in the art world. Looking back at her forty-year-long career, I can see she was ahead of her time for many of her lines of critical artistic inquiry. We sit in the artist’s 150-plus square meter apartment on Vienna’s Naschmarkt, the night market, right next to Otto Wagner’s Jugend style Majolica House, which is multi-functional; it serves as Widauer’s studio, archive, home, short-term housing for visiting art and music professionals, like myself, that she has met along her way, and a venue for her infamous salon-style dinner parties. When I find out that she is planning to partner with an institution to host an exhibition centering a fictive artist persona, to be held in the apartment, I consider that her life there might actually be likened to a sketch that precedes a painting. An embodiment of blurring the boundaries between fantasy and reality, a space that many artists inhabit. In 2020, in her exhibition Villa Nix at Kunstmuseum Olten she invited viewers to explore seven rooms in an imaginary home that she created for herself and her art—her apartment exhibition will be a continuation of this generous look into her mind.

“I love maps, plans, the idea of discovering hidden rooms. To find a treasure. To invent another life, to express beauty through the frame of an invented interior, be it a body, a house, a shell a planet, a nest: in the sense of philosophy, color, smell. In a way, it’s private, but put out in the world, in the light, it becomes an investigation or an artwork,” she says.

Our interview is ad hoc; it happens in parts as we cross paths in various rooms. Me taking a break from writing, her preparing for her next trip—she is constantly in motion. Old and new works lean against walls, pile on the floors, or are installed on walls or in shelves, some awaiting to be packed and sent to various institutions, others simply on display. Perhaps as a reminder to pick up a thread, to continue a conversation. A robust book collection lines the shelves in her library, and a doll sits on the sofa. It is a doll with the face of the Viennese painter Oskar Kokoschka, who, after his relationship with Alma Mahler ended, had a life-size puppet in her likeness made. It accompanied him around town, to the opera, and parties. It appears in his paintings, and when he retired her, he gave a party in her honor and beheaded it. Concurrently, Mahler moved in the same circles. “Deeply disturbing,” Widauer says, and I agree. Part of a larger series, her male and female dolls with his face reflect on the role of female muses and the objectification of women in the art world, and those who silently look on.

Living between Vienna, Basel, and the Italian Riviera, Widauer is constantly on the move. She calls it a triangle of love: “culturally these are three highly active countries with a long cultural history and a lot of contemporary cultural achievements and movements.” Vienna, however, where her largest studio is, and its creative set, past and present, has served as a starting point for many of her projects. Often interwoven, one leads to another.

For instance, in 2014, she built a “rocket,” a pile of the instrument cases belonging to the musicians of the Vienna Philharmonic, which was first exhibited in the Belvedere Museum’s Carlone Hall. To restage the piece in the United States, she needed one additional harp case, and the New York Philharmonic offered Steffy Goldner’s case, newly acquired but belonging to their first female musician working between 1922-32; they did not hire another female musician until Orin O’Brien in 1966. Goldner also happened to be Austrian. It led her to create a video art installation around Goldner’s life story—she left Vienna before the Second World War in hopes of earning a living as a musician in New York. “The Special Case of Steffy Goldner represents a way of working between precision and intuition, and the product of joint research,” she explains. Together with the NYPhil’s archivist Gabryel Smith, they tried to understand her life through interviews with relatives, letters she left, archival information, and films they found. Widauer continues, “it was a non-didactic, but deeply inspiring experience.” I had the pleasure of moderating a panel between Smith and Widauer before it went on view at David Geffen Hall, in 2020. The piece traveled to the Austrian Cultural Forum in D.C, the Swiss Embassy in New York, and the New York Historical Society.

At her kitchen dining table, one evening, we sit drinking wine and talk about her friends, collaborators, and how her career has flowed. I find it interesting that Widauer’s video design work—incorporating video and projections in opera, theater, and other stages—when the technology was new in the 1990s, allowed her to gain a living while developing her artistic career. “I experimented and experienced a lot with the design work and my ‘pure’ art work—I love closed-circuit situations.” Early in her career, she became known for her video art, and Wulf Herzogenrath curated her work, among others. One of her video art pieces is on view, screening on the wall with a projector in her library. However, writing, drawing, sculpting, and painting remained a constant. Like most, her progress has not been linear: “I grow and learn and explore, I dream and film and paint, I cook, I love, I cry, I question, I dance, I swim, I mourne, I read, I write I speak, I listen, I breathe, I argue, I consider, I smell the roses, I am anxious. I am human, I am nature,” she says with a twinkle in her eye, tucking blonde strands of hair behind her ears. She’s equal parts quirky and put together, her feet are on the ground, but her head is in the sky—a body she often revisits.

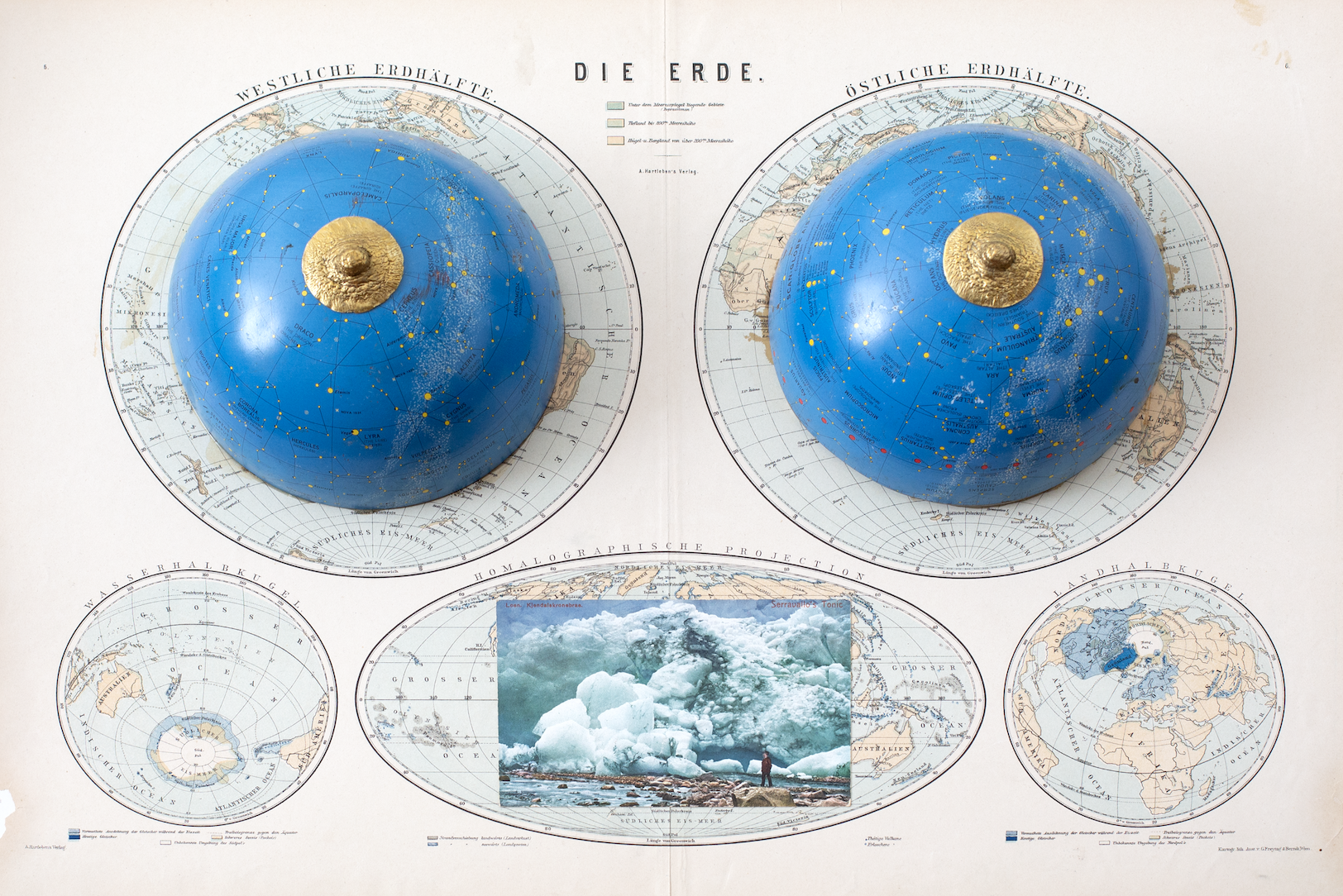

“I am attracted, as most of us, to the skies, the clouds, the planets, and the stars,” she explains as she shows me her book on meteorites. It is an anthology featuring close to thirty authors that she dreams of publishing in English. “Our bodies are partly made of interstellar material; we are not only connected with the universe, we are simply part of it, also physically,” she continues. The natural world, and thinking of our bodies as part of it, is a cornerstone of her practice. Humiverse and Skyboobs merge elements from the sky with the human body, in the former she has punctured holes that follow constellations on a large-scale drawing of the human body framed between two pieces of glass. And, the latter are sculpted breasts of the sky.

More recently, she is concerned with organizing her archive. What are your methodologies? I ask, considering the importance of creating a repository for artists who mostly show institutionally and flit between galleries. But also, more radical modes of archiving, how to traverse its conceptual boundaries, having just read Kate Eichorn’s The Archival Turn in Feminism. “It’s a bit like dreaming and weaving, as I try to find the essence of it in itself. It’s digestion and invention, innervision, and projection into the outer world,” she explains. An archive is not just a collection of material; it is also a way to control and share your narrative and invite others in. “Connection with the you, the me,” she adds.

When I ask if she would do anything differently, she responds: swim like a tree, dance like a bird, laugh like a dolphin. And, I think that she does all these things already.

Nives Widauer is on view at The Thin Thread Line at /SAC (Spațiul de Artă Contemporană) through August 16, 2025.

You Might Also Like

“Is This Intimacy?” on view at Krinzinger Projekte in Vienna

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.