Despite Tense Relations, A Pro-Ukrainian Video Art Platform Stages its 29th Program

It is sometimes hard to navigate both sensitivities and sensibilities to support Ukrainians suffering from the war but it is key to be malleable in developing programming to adapt to the changing landscape of needs and knowledge. The International Coalition of Cultural Workers in Solidarity with Ukraine, a coalition of artists, scholars, and curators, attempts to do just that. They are a group of Belarusian and Ukrainians who over the past year have organized twenty-eight events across Europe in major venues such as Documenta Fifteen, Venice Biennale, The European Pavilion in Rome, and Manifesta in Kosovo, but also in Kyiv. The center-point of their activities lies in developing their online platform (antiwarcoalition.art), an archive of art from 2014 and onward related to the war submitted through an ongoing open call.

The onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine brought about many opportunities for Ukrainian cultural workers and artists to participate in the international art world. Before the escalation of the war, working was made more difficult by combinations of procuring visas, currency exchange, and an overall lack of knowledge of art from the region. Now leading European institutions are clamoring to Ukrainian cultural workers through grants, residencies, and lecture opportunities made easier by the EU’s fast-tracking of work visas. Even universities are offering Ukrainian students free degrees in the arts. In this fraught time care is of the utmost importance.

As the war rages on, least we do not forget that there is a deep sorrow and anxiety tainting interest in the region and that Ukrainian artists and cultural workers are tired and suffering as they fight for their very existence. Most just want to rebuild their country in peace.

“We are living in a parallel reality,” says Ukrainian-born digital artist and coalition co-founder Maxim Tyminko who works with algorithms. Currently residing in Amsterdam, he studied art in Belarus and Germany. He explains that although he follows the news in media and first-hand accounts from friends and family, he cannot experience or grasp how a soldier in the field feels. He also stresses that the momentum around supporting Ukraine must continue. “Which is why art as a form of communication and storytelling is important,” he said.

Making sense of or embodying the unimaginable, the coalition’s video art platform is another way to engage with, provide care, and process this devastating geo-political event. At the beginning of the war, the coalition felt that it was important to spread the word about the war’s underlying global impact to shore up support for Ukraine. Their idea was “to go into public space with art and scream, shout, and show and spread moving messages,” one of their members explained when we meet over Zoom.

“From the very beginning we included the works of artists from different countries to show interdependence and that the war is not only a conflict between Ukraine and Russia, but affects the whole world,” says co-founder Antonina Stebur. The platform presents work by artists from Ukraine, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Germany, India, Mexico, the Netherlands, Serbia, South Africa, Turkey, and the United Kingdom, among others.

Over the past year, they have developed programming that engages with multiple facets of the war—care and its infrastructures (59th Venice Biennial), non-human agency (Documenta Fifteen), and the global economic impact of the war (Weltkunstzimmer), among others.

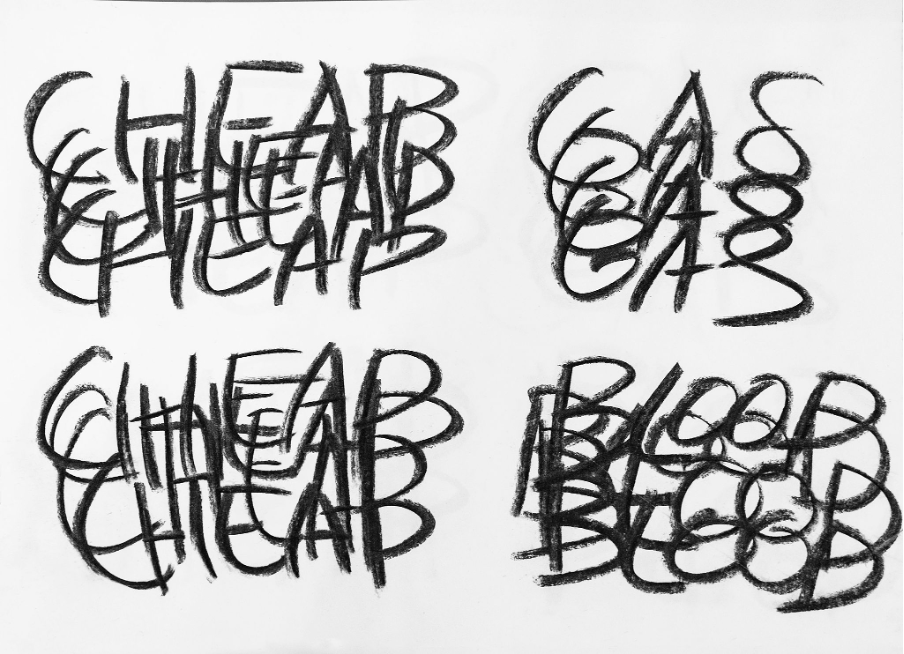

The celebrated Ukrainian artist Nikita Kadan is archived on the coalition’s platform. One of his video works from 2022 was included in the collective’s exhibition “𝖭̶𝖨̶𝖢̶𝖧̶𝖳̶ UNSER KRIEG” at Weltkunstzimmer in Dusseldorf that closed earlier this month. The title, Our War, reacts to an anti-war slogan present in public spaces through graffiti and posters throughout German cities: “das ist nicht unser Krieg!” This is not our war. Bringing together Ukrainian and international artists, the exhibition highlights that it in fact is a war that affects us all by altering the distribution of labor, food supply chains, and the energy sector. Kadan’s piece opens with the words: “Cheap Gas, Cheap Blood” and continues with “Fuck War.” Commenting on the global economy that has been affected by a sharp rise in gas prices due to a shift away from Russian gas.

Allyship and inclusivity is a leitmotif for The International Coalition of Cultural Workers in Solidarity with Ukraine. Seven Belarusian artists and cultural workers formed the group at the beginning of 2022 and six remain Valentina Kiselyova, Lena Prents, Antonina Stebur, and Anna Chistoserdova in addition to Aleksandr Komarov and Maxim Tyminko who both are artists and have work on the platform. Like many collectives, the group expands and contracts in response to its participants’ needs. Currently, they have two Ukrainian members Natasha Chychasova and Tatiana Kochubinska. Both Komarov and Chistoserdova stressed the importance of engaging Ukrainians early to become coalition members in order for them to develop programming in support of their mission. Importantly, through its inclusive mission, the coalition invites non-Ukrainian voices to take part in conversations about the war positing that it effects the global community.

Since Belarus is an ally of Russia, Ukrainians are suspicious to its people. Belarus president Aleksandr Lukashenko has allowed Russian tropes to pass into Ukraine through his country’s borders, he has vowed support of Russia, and the two countries have joint military drills. With its authoritarian leader, many Belarusian are marginalized as the country is rife with violations of human rights including to freedom of expression, assembly, and association. According to a report from the UN in conjunction with the last election at least 37,000 people were arbitrarily detained between May 2020 and May 2021 and by October 270 NGOs had been closed down, and by the end of 2022 thirty-two journalists had been detained and thirteen media outlets declared “extremist.” Because of Lukashenko’s support of the Russian invasion, many Ukrainians are not open to building solidarity with Belarusians—even if they are politically opposed to their president.

Not all Ukrainians share this sentiment. Kochubinska, who is Ukrainian, was an early joiner of the curatorial collective. “I cannot judge people based on their nationality or passport,” Kochubinska tells me. But she understands those whose relationships have become tainted by the aggressive military invasion.

New immigration reforms directed to support Ukrainians have helped Kochubinska find stability in her career. Currently residing in Germany, she received her residency permit while she was a fellow at ZKM in Karlsruhe—this would not have been as expedient before the reforms. Since January, she holds a full-time curatorial position at SKD Staatliche Kunstsammlungen in Dresden. However, she still maintains her freelance work. In addition to her work with the coalition, she is responding to the urgent need to amplify Ukrainian culture by co-curating “Kaleidoscope of (Hi)stories. Ukrainian Art 1912–2023” opening at Albertinum in Dresden in May. Having worked as a curator at PinchukArtCentre, Ukraine’s leading museum for contemporary and modern art, specializing in Ukrainian art she is apt for the task.

Cultural programming in support of Ukraine tends to look different in Europe and the United States. In the United States efforts to support Ukraine often incorporate the Ukrainian diaspora and other voices. In comparison to Europe, the influx of Ukrainian refugees in the United States are fewer. So, Ukrainians who emigrated to the U.S. before the war and—this is where it gets tricky—some who were born in what is now Ukraine and others born in other Eastern Bloc countries are important figures in U.S. advocacy. Therefore engaging non-Ukrainians is common in panel discussions and conversations, which for a coalition of Belarusian and Ukrainian cultural workers is a benefit.

Later this week, on March 18th, The International Coalition of Cultural Workers in Solidarity with Ukraine will open their first exhibition outside of Europe “Sovereignty Imagined” at Maenad Collective in Brooklyn. The exhibition features seventeen video works from the online platform selected by local curator and moving image artist Alex Faoro who has also included a work created with his wife and co-collaborator Helena Deda, who grew up in former Yugoslavia. Works included investigating war, border conflicts, demilitarization, historical revisionism, and memory and form a wider conversation on the politics of sovereignty and related statelessness and utopic futures. With its history of slavery and hegemony on the world stage, the United States seems an apt place for the coalition to problematize sovereignty.

The earliest work included in the presentation is “Letters From Ukraine” a video piece by Oksana Chepelyk from 2014. When Russia invaded Crimea. It is the real eyewitness account of Zanna Nedzelska as she was trying to escape the city with her son. In the piece, a woman and boy run through the empty cityscape stopping every now and then to grab and shake their heads and clap their trembling hands against their bodies. Thus illustrating how fear and neurosis physically take hold. At one point the boy drops his backpack. Marking the precedence of bodily safetey over physical possession, they just keep on going. A voiceover narrates a letter that describes how the city has changed; jewelry stores have been looted and have moved and citizens have fled their apartments making way for brothels and narco-stations to cater to the Russian occupiers—new economic systems replace old ones. The imagery does not convey what the narrator describes; the sky is blue and the sun beats down over a city that is empty and still, we must imagine it all. Its evocation of isolation, loss, and longing makes the piece especially powerful. Today Luhansk is annexed by Russia.

Shortly after Russia’s full-scale invasion, Brooklyn Rail organized a panel “Solidarity with Ukraine.” To the ire of members of a New York-based group formed earlier in the year Ukrainian Artists and Allie’s League (UAAL) it included several Russian and Belarusian born cultural workers—coalition co-founder Chistoserdova participated. The league found it too early to include non-Ukrainian voices. Chistoserdova support for Ukrainians and narrating the negative effects of the war through curation is extensive. But understandably tension between Belarusians and Ukrainians has increased as a cause of the war.

A Ukrainian participant in the first panel and UAAL member Adriana Farmiga responded to the critique and was met with the opportunity to organize the second iteration of the series “Ukrainians on Ukraine” in which she brought together a group of Ukrainian born cultural workers and artists with the help of Ukraine-born, U.S. based artists and UAAL members Katya Grokhovsky and Slinko. Speakers included Lizaveta German co-curator of the Ukrainian Pavilion at the Venice Biennial. Some shared their first-hand experience of fleeing the war while others pinpointed how Russian narratives penetrate academia and media to promote the notion that Russian culture is overarching in Eastern Europe while placing Russia as a big brother of Ukraine. To protect their sovereignty, Ukrainians have been working for decades to highlight counternarratives that dispel this misconception rooted in imperialism. I raise this example not to critique Brooklyn Rail but to illustrate that putting Belarusians and Ukrainians in the same room is sometimes met with skepticism (adding Russians is mostly out of the question) but also that we must allow cultural organizations to both respond to their public and make mistakes if they are willing to correct them.

In March 2022 MoMA opened “In Solidarity,” a show featuring art from the 20th and 21st century with artists born in what is now Ukraine including Sonia Delaunay-Terk, Ilya Kabakov, Kazimir Malevich, and Louise Nevelson. Many of the featured artists went on to live and thrive in Russia and other places but they were born in what is now Ukraine. Default ascribing artists as Russian when nationalities may be muddled is a common problem at museums. MoMA’s focus on Ukrainian ethnicity and place of birth served to correct some of these wrongs while highlighting the importance of Ukraine’s own nation-state.

Incorporating a contemporary perspective and responding to the war, in conjunction with the exhibition, MoMA hosted a conversation between scholars and artists titled “post presents: Art, Resistance, and New Narratives in Response to the War in Ukraine” which focused on Ukrainian art post-1991 and post-2014 until today moderated by Inga Lāce, MoMA’s C-MAP Central and Eastern Europe Fellow. Investigating myth-making, artist Lesia Khomenko who is living in exile in Los Angeles, attended in person to show paintings that she had painted of her husband, currently a soldier at war. The increasing division between men and women is something many struggle with but must contend to. While artist Nikita Kadan, (who was included in the coalition’s exhibit “𝖭̶𝖨̶𝖢̶𝖧̶𝖳̶ UNSER KRIEG”) joined over a video link from Ukraine to deliver his thesis on how to look at Ukrainian avant-garde art through a decolonial lens but was cut short due to time constraints. There is much to be said. His advocacy related to the war and the politics of Ukrainian monuments and art history are easily found online for those who are curious to delve in.

Speaking with parts of the collective it is clear that they have deep-seated connections to each other but also that they not only respond to but incorporate their environment in their curatorial process. Komarov stressed that in every city they organize in “there are local people who have been engaging with similar topics for a long time and that building a community in each of these cities is very important for the platform.” At Documenta Fifteen they were invited by the Cuban artist-activist Tanya Bruguera to participate. Their funding comes from various sources including Goethe Institute; Danish Cultural Institute in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia; European Cultural Foundation; House of Human Rights Foundation, and the US-based Trust for Mutual Understanding.

The group has navigated many hurdles in its mission to build inclusive support for Ukraine. Formerly the coalition was named Antiwar Coalition but for its pacifist connotation, they recently chose to change their name. The online platform remains unchanged. When they organized an exhibition at Dymchuk Gallery in Kyiv—that also doubled as a space to access electricity, WiFi, and tea during blackouts—they were met with suspicion and self-censored themselves by removing the name of their organization and downplaying its Belarusian roots.

Untangling relationships, uncovering Russian-backed narratives, and being cognizant of allies who support and others who draw attention away from the issue of war and toward Russian imperialism is important. Members of The International Coalition of Cultural Workers in Solidarity with Ukraine know that they will be criticized and respond by further developing programs and working groups that promote sensitivity toward the Ukrainians they support while highlighting the war as a global issue. In many ways, they are at the forefront of building new cross-border relationships that unify anti-Russian cultural workers and artists from across the Eastern Bloc. Most coalition members have a history of investigating the intersections between art and activism, democracy building, and resistance, and cannot change their place of birth.

Quoting Ukrainian artist Kadan, coalition member Komarov says that: “drawing the war is a form of self-therapy.” And, for this curatorial collective, the larger part who have experienced persecution or flight from their homeland organizing programming to highlight and support Ukraine in the war has the same effect.

Sovereignty Reimagined is on view March 18-24, 2023 at Maenad Collective, 46-55 Metropolitan Avenue, Suite 305 Ridgewood. Public opening reception on March 18th at 8:30-10 PM and closing reception on March 24th at 8:30-10 PM.

You Might Also Like

State of Becoming: Katya Grokhovsky in Conversation with Leeza Meksin at Ortega y Gasset Projects

Art as an Act of Hope: The Ukrainian Pavilion in Venice and Artists in Flux

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.