This Fall, Loaded Sentiments Take Us To Queer Places

As a curator, I am interested in affects that are often deemed minor, insignificant, or rooted in the everyday and I allow myself to drift toward these affects without necessarily narrativizing a concrete chain of cause-and-effect. When I was organizing the group exhibition To Save and To Destroy at BANK this summer, I intuitively understood that I must attend to lyricism, melancholia, nostalgia, and sentimentality, in an otherwise performatively optimistic season of group shows that celebrate claims of joy or dissent or simply indulge in the heat of summer. Metaphorically, the exhibition mostly comprised of painting (or painterly works) and photographs that sit comfortably with the aftermath of deep sadness, wanting to move forward, yet with each step clumsily caught up with lingering aftershock. Now looking back, I cannot help but speculate that sentimentalism, aesthetically and curatorially, as a method and a feeling, is no longer a subgenre, but will become a dominant mode of hermeneutics in years to come, given our gradual loss of most liberal consensuses that connect us to the world.

Several exhibitions currently on view in New York lean into these themes, At Greene Naftali, Dominique Knowles’s exhibition, The Solemn and Dignified Burial Befitting My Beloved for All Seasons, mostly features recent paintings depicting earthen landscapes, ruminating with the spectral presence of a suggested horse and a mourning rider, both dispersing into the artist’s aerial swaths of paint. This body of works was initiated after Knowles, himself a devoted equestrian, lost his companion horse. However, Knowles’ brushstrokes, elegantly minimal and transparent, aloofly conjuring scenes of loss just on the edge of legibility yet still tethered to traces of emotional reality, quickly ascend beyond an event of individual death and channel primordial histories or a priori memories before the invention of grammar. Evidently, these paintings are citing and animating imaginaries surrounding cave paintings, which are perhaps the first depictions of horse as a companion species and a deity. Is Knowles offering a beautiful tale, that in each encounter with more-than-human kinship, one is also, voluntarily or subconsciously, remembering and experiencing the original genesis of more-than-human kinship, inherited as memories—wordless, only images—in our collective unconscious? Even for the affected and deeply spiritual Knowles, details of human’s first chance encounter with horse remain fuzzy. Nevertheless, these partially forgotten episodes of affection, grasped through mere evocations, can still generate intensities of desire, for returning to a nature that wrapped all around us. Frustrated intimacy is transformed into another hope for union, however distant or remote the goal is.

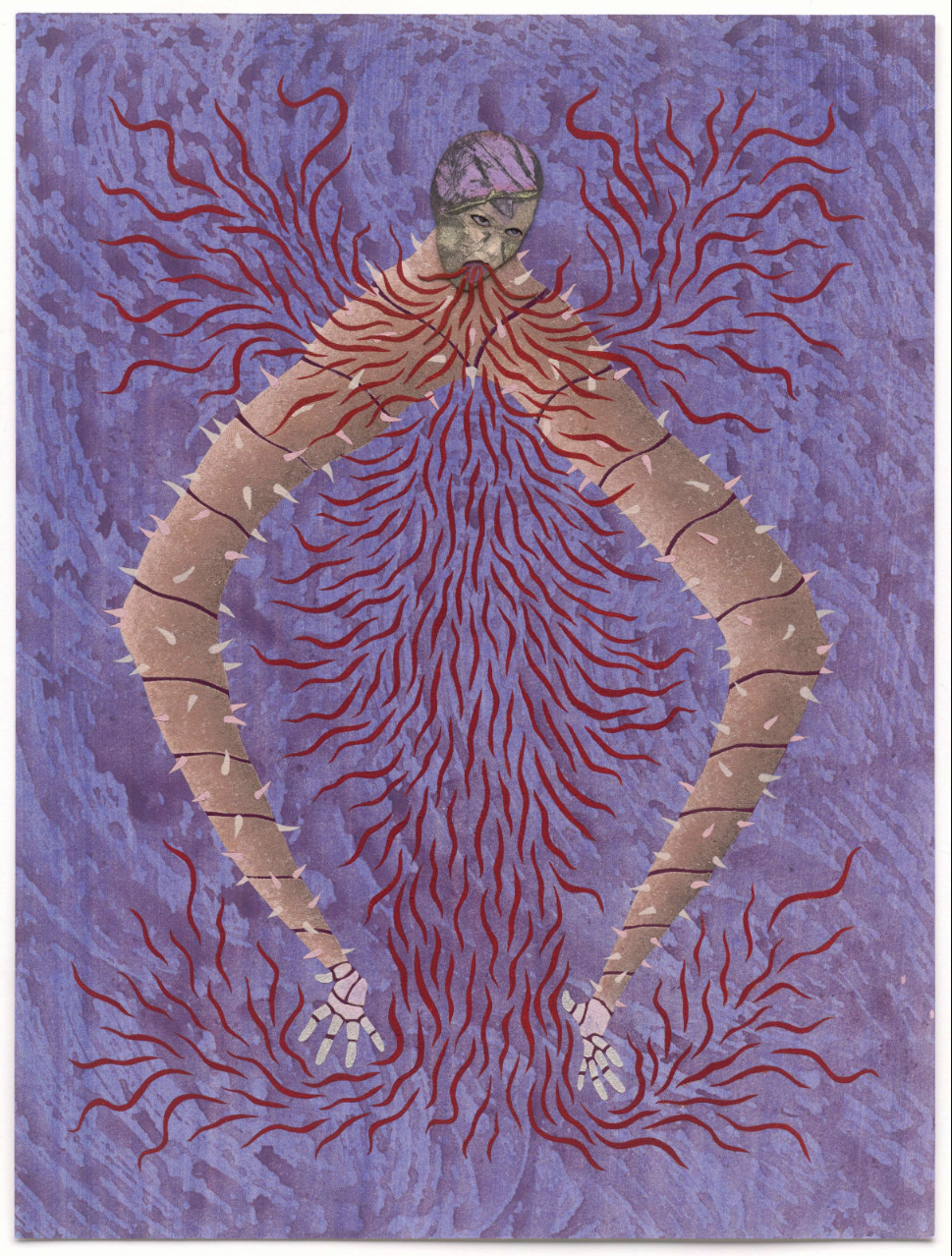

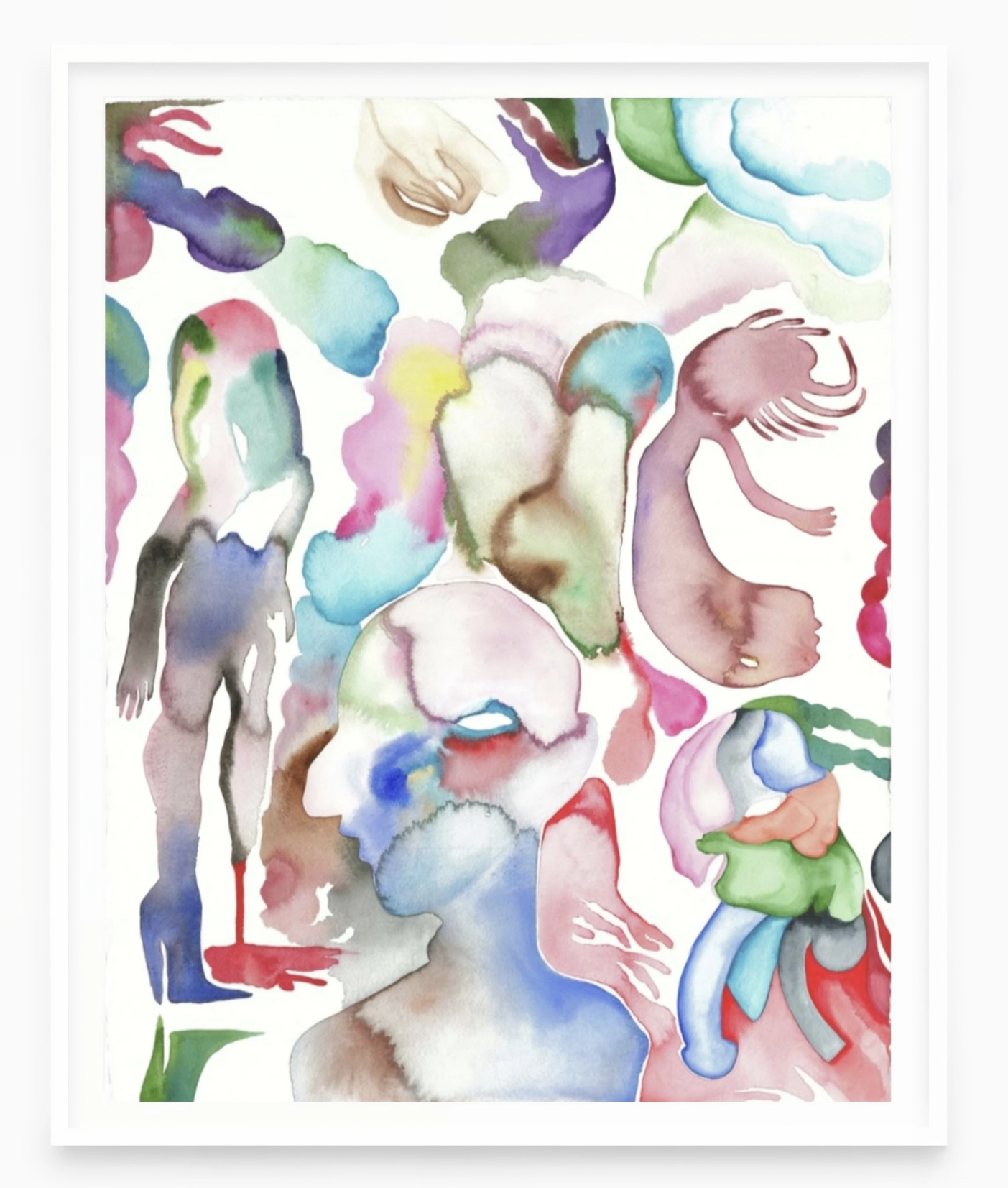

The bygone world in which God(s) and human are in constant communion is felt in Felipe Baeza’s Beyond the Vessel, 2024, on view in Gesture and Form Zeit Contemporary Art’s most recent online viewing room. Against a backdrop of purple whirls, an androgynous head floats, twirling its elongated, stitched limbs, while filaments of red tendrils flow outward from the figure’s mouth, as if they were emanations of energetic reverberations, alluding to the shared Latin etymology of breath and spirit. Remixing mythologies of Indigenous America and Catholic iconography, Baeza creates an image that humanizes deities and expresses godly potentials of the human figure, collapsing the distance between the two ontological positions. Curiously, Baeza’s interest in the liberatory potential of religion seems to be an example of the surgency of queer and Indigenous world-building among a new generation of artists from Latin America, among them La Chola Poblete. Poblete’s work on paper Untitled, 2023, also on view at Zeit Contemporary Art, delights in Andean syncretism and depicts, with free-flowing watercolor and ink, various gender-fluid and indigenous feminine figures, possibly reworked silhouettes of Virgin Mary. It is telling that Baeza donated his work to The Immigrant Artist Biennial to be sold in favor for their programming, supporting artists of his immigrant artist community. And, that Baeza and Poblete were featured in the Venice Biennale two years apart, marking an not only an interest in the body, eroticism, and strategies of abstraction to approach gender, but cosmology overall. Baeza and Poblete’s theology, a theology unmoored from dominance and gesturing toward collective desire for immanent, harmonious coexistence, further points to how far the domineering mode of theological thinking, under siege from hatred, is from these original more-than-human experiences.

All we have is longing for lost worlds, such is the case for Yu Ji’s Flesh in Stone – Spontaneous Decision No.4, 2025 and Patricia Ayres’ 2-12-1-14-4-9-14-1, 2025, both new commissions for Sculpture Center’s current group show to ignite our skin. Yu’s sculpture imagines an incomplete body forming and evolving from stone. Its fluctuating contour, yet to be fixed into legible shapes, is an investiture of pure potentials, a reminder of countless mythologies in which divine interventions sustain life cycles. Ayres’ larger-than-life, hovering flesh tower, made from heavy-duty elastic, can be read as an allegory for a spiritual wish toward a world of union among body, spirit, and logos, a world before flesh becomes burden. Yet again, reality strikes fast, rendering them monuments for the impossible, or excesses from the castrated imaginary of bodily omnipotence.

Loaded sentiments take us to queer places. P. Staff is a melancholic realist insofar as they are acutely aware that one can never escape the architectural unconscious even when enacting subversive desires. The centerpiece of Staff’s exhibition Possessive at David Zwirner is Penetration, 2025, a film where the actor’s body rather fails to be penetrated. The green laser supposedly reaching into his intestines reveal or engender no cavitas, but beams with more mystery, becoming its own source of seduction. The actor’s body, projected as three sections onto the gallery’s central column, corresponds to the architecture and its slippery semantic associations: The actor’s mostly still gaze is on the upper floor, while viewers observe his breathing chest on the ground floor. Sound installations of heartbeats, whispering, and broken piano keys further ground the film in its immediate environment of bourgeois domesticity and its concomitant Oedipal drama. Clearly, the actor’s body is a proxy or surrogate for Staff’s desire, which is a masked desire to decipher the administration and operation of desire. In doing so, Staff alienates queer sex and its duration of improvised gestures, repositioning them in and through disciplinary power, as seen in Staff’s slick latex BDSM-inspired sculptures—their restraining armatures abort their eroticism, suspending them as artifacts rather than living experiences. Possessive reveals the tragically asymmetrical relation between desire and one’s capacity for desire.

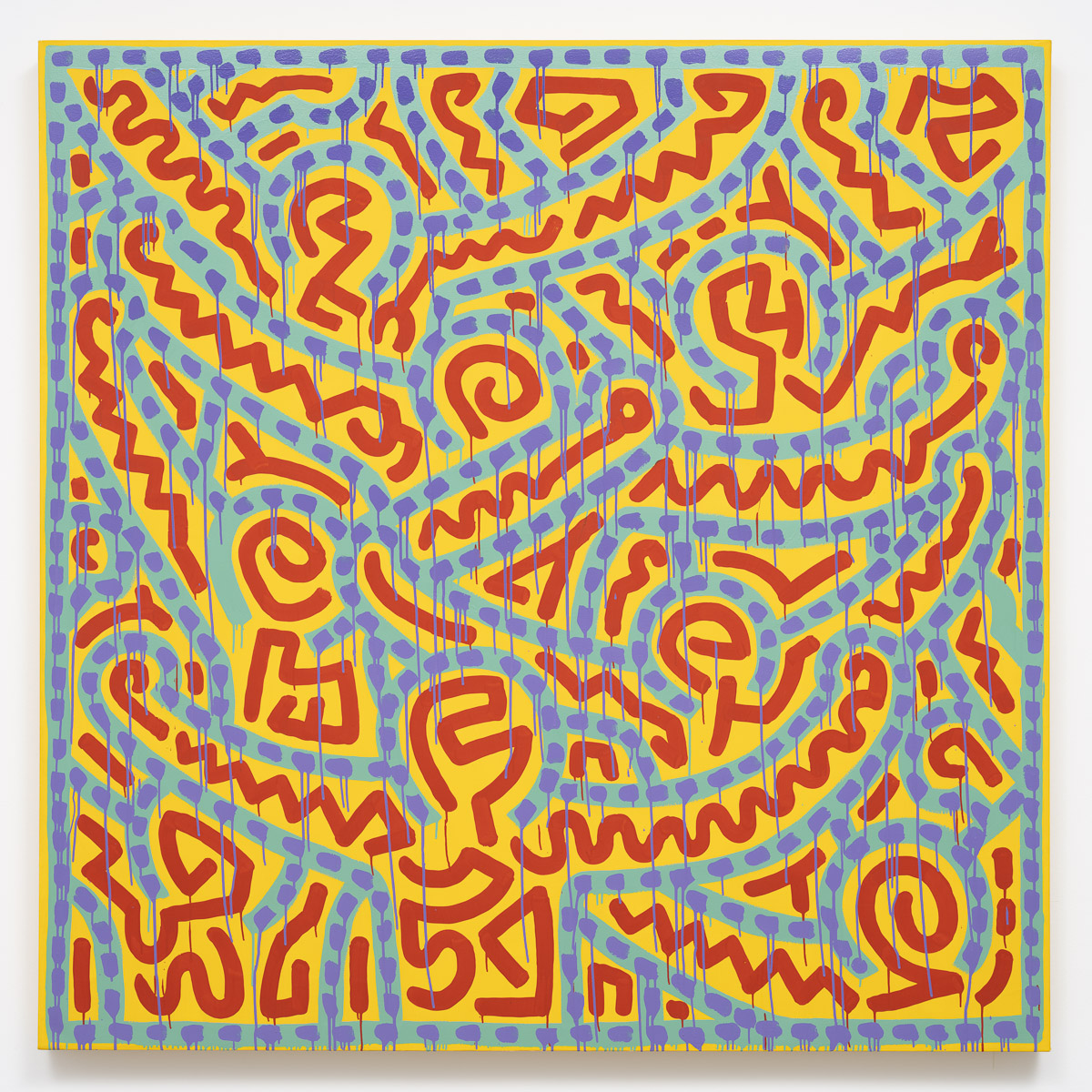

A different kind of melancholia cannot be ignored in Liberating the Soul: Keith Haring’s Paintings at Gladstone Gallery, which showcases Haring’s late-career paintings. When so much of Haring’s exuberant patterns have been inversed into parodies, simulacra, and pretensions of neoliberal individuality, it is hard to see these paintings as what they are: phalluses or scenes of anal sex. Crude materialism would have reduced them into anatomical studies, but Haring was painting in a time when homosexual desire and its death drive can still be disruptive to notions of self, agency, and revolution. Each fated chance encounter in the bathhouse or cruising park became a determined reproduction of the desire for creative annihilation. And the melancholy of seeing Haring’s painting now lies in the untimely demise of such desire, hollowed out and incorporated into capitalism’s management of diverse bodies.

Sentimentalism today is less a retreat into softness than a curatorial insistence on affect as a mode of survival. Through mourning, spiritual syncretism, queer desire, and bodily vulnerability, artists in these five exhibitions (six including my own) are reanimating sentiment as a critical language—one that resists cynicism and reclaims intimacy, memory, and longing as necessary orientations in the face of fractured worlds.

Dominique Knowles: The Solemn and Dignified Burial Befitting My Beloved for All Seasons is on view through October 25 at Greene Naftali; Possessive in on view through October 25 at David Zwirner (NY: 69th St); Gesture and Form is on view through September 26 in Zeit Contemporary Art’s OVR; to ignite our skin is on view through December 22 at Sculpture Center; Liberating the Soul: Keith Haring’s Paintings is on view through November 1 at Gladstone Gallery (NY: 24th St), and the writer’s exhibition To Save and To Destroy was on view 10 July – 13 August at BANK New York.

You Might Also Like

What's Your Reaction?

Qingyuan Deng is a curator and writer, based between Shanghai and New York City. He is interested in relational aesthetics, experimental filmmaking, and the intersection between literary culture and visual arts.