HOUSING Gallery: How Legacy and Community Guide the Fierce Supporters of Artists of Color

Since its inception in 2017, New York’s HOUSING gallery has played by its own rules. Demystifying sales, thoughtfully fostering artists’ careers, and fighting against the increasingly toxic practice of immediately flipping works at auction, HOUSING is a refreshing model that places legacy above sales. With a strong curatorial perspective and unwavering dedication to supporting artists of color, HOUSING has quickly made a name for itself as a space for critical engagement. What truly sets HOUSING apart is what goes on behind the scenes.

Founded by KJ Freeman and Eileen Skyers, HOUSING aims to de-gentrify the art industry by focusing on emerging artists of color. Freeman, who now runs the gallery along with director Shani Strand, gave us insight into the ethos of HOUSING and how they’ve worked to support artists of color for the last four years. “We started out by showing a lot of emerging black artists who are now more visible and better known.” She explained. “We were never just looking for the next big name in black art. These were people that I was constantly in conversation with about divesting from the art world.” After the original Bed-Stuy location was sold out from under them in 2018, HOUSING eventually landed in the Lower East Side, where it remains today.

Going beyond the traditional commercial gallery model, HOUSING also steps up as a community center when needed, as was evident during Black Lives Matter protests last year when they handed out supply packs, provided bathrooms, and held a vigil. Woven into their ethos, community engagement often comes unplanned and purely out of a response to the needs of the moment. As Freeman put it, “The community outreach side of things has evolved naturally and spontaneously out of anarchic situations. When it becomes necessary, we try to fill that role. We’re thinking of having a more structured, organized function as a community space, but it’s really just part of our politics and daily operation that works well when it’s more organic.”

One of their recent community outreach projects came early on in the pandemic when HOUSING started a mutual aid fund and gave out several microgrants and five $1,000 grants to black and brown women artists. “Providing aid is just a part of our practice. Other grants exist, but when people really need the funds, they can’t wait around. Even now, if someone reaches out and they need a microgrant, we really try to help.”

HOUSING’s recent exhibition “A Gathering” embodied this community ethos. Inspired by the Lower East Side anti-establishment arts non-profit, A Gathering of the Tribes, the show brought together 12 artists and honored the life and legacy of Tribes’ founder, Steve Cannon. Part of Freeman’s curatorial vision was to make the gallery space feel like a contemporary recreation of the vibe of Tribes during Cannon’s time. Along with Strand, she selected New York artists, as well as artists who work in traditions similar to what would have gone through Tribes, and installed the show in a pseudo-salon style, a nod to how it might have looked hanging in Cannon’s home. The traditions touched upon included pieces relating to the body in line with David Hammons, and works building upon the legacy of artists like Charles White who focused on black daily life and culture. Adding an interdisciplinary layer inspired by Tribes’ 2012 “Exquisite Poop” exhibition, “A Gathering” was accompanied by a zine of written responses to the works in the show.

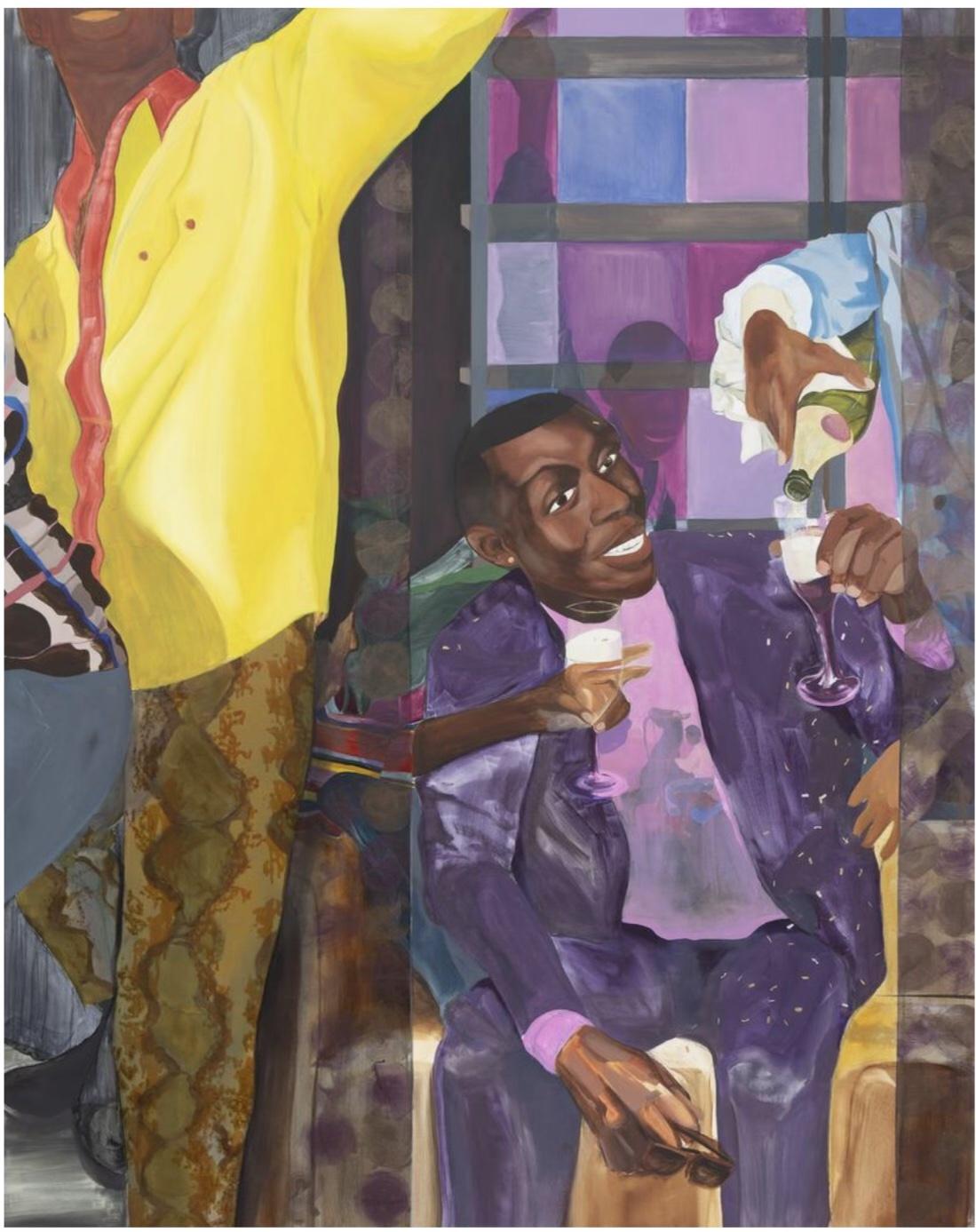

In line with the legacy of artists like Charles White was a painting by Nathaniel Oliver. Titled “Jazz,” Oliver’s piece featured a cool, nonchalant, black figure in a purple suit sitting in what appeared to be a jazz club. Holding a pair of black sunglasses in one hand, he smiled at his other hand with its glistening champagne glass being refilled by a figure behind him. The accompanying zine entry, written by Freeman, also embodied this sense of jazz and added an underlying tone of nostalgia.

Also in the show were two pieces by Taína Cruz, including “Boi Scouts of America,” which depicted an ethereal portrait of a man drawn in charcoal. Recalling Hammons’ body prints, the figure contrasted with the washy, burnt-orange background. Installed near Cruz’s painting and also referencing the body was Ladder To The Top by Emmanuel Massillon. Leaning against the wall, the work combined a wooden ladder with a small figure on top, also made of wood and recalling the tradition of carved African masks and figurines.

While “A Gathering” pointed to the similarities between Tribes and HOUSING as spaces open to community, collective engagement, the connections go beyond the exhibition itself. Stemming from the collective ethos, legacy is a large part of how the two spaces function.

Freeman explained, “A lot of important figures have gone to Tribes, which creates a strong sense of legacy. Artists who choose to show at HOUSING do so in ties to our legacy and because we’re not market driven. There’s a history of black run spaces where they don’t function the same way as a traditional commercial gallery–not as money oriented and not just working to uplift the gallery’s own program–and I think that draws artists to us. This is true for any artist-run space or community-run space where the incentive is to show your work and to sell in a way that helps you in relation to your market and your career.”

Freeman’s insight into sales is in part a reflection of the increasingly common practice of immediately flipping works by artists of color at auction. While this occurs to all artists, results over the last few years have been particularly shocking for artists of color. One noteworthy example is Amoako Boafo, who skyrocketed to art world fame in 2019 and watched as his highly sought-after paintings were unfairly flipped for upwards of a 3,800 percent return just months after they were purchased.

For HOUSING, reflecting on the market for black art in general is important in how sales decisions are made. “There’s a sort of hesitation and scrutiny about the market now because of everything that happened with Amoako and the abuse of black artists’ works flipping at auction, so we’re really thinking of how that affects things, especially in relation to black figure painting.” Freeman explained. “There’s definitely people who’ve tried buying from HOUSING that I have said no to because the sale could jeopardize the artist’s career, or there was a possibility of the buyer just looking to flip. I have heard stories of people who have had to buy a work back because they didn’t want it to be put on auction. No one wants this to happen. I’m always in consultation with the artists about sales, which most galleries are super shrouded about because they want to be able to put a stamp of ownership over the artists.”

Freeman added that her relationship to the art market has always been, “from being in the trenches.” She explained, “I didn’t go to Sotheby’s. I don’t have training in that sense and I’m still learning. There are so many intricate things and I’m not rushing to sell to anyone without considering all of these and consulting with the artists.”

The rush to buy and sell can contribute to an overall fetishization of black art and artists. In part driven by Instagram and the increase in artists’ own celebrity personas, fetishization of any art can lead to a flattening of creativity. As Freeman noted, “There’s definitely an issue of artists being influenced by Instagram and the whole party circuit. I do believe artists should be in the studio doing work and not having to be pressured to network and push themselves to be seen at parties. There’s a lot of hot air right now that I think is flattening the whole movement. Collecting art should be about preserving the legacy of black radicality, not about fetishizing objects.”

Curatorially, Freeman will increase her focus on queer black artists. “I have always supported queer black artists, and I’m getting concerned that there’s a flattening of radical identities and radical spaces, so I’m especially interested in queer identities. My programming in the next year or two is going to be shifting more towards that particular space.”

In addition to this shift in Freeman’s curatorial focus, HOUSING has an upcoming show, “Thick Like Dumpling,” opening June 10th. Curated by Sucking Salt, a collective consisting of Shani Strand, Zenobia Marder, and current students at UCLA, the show will feature artists Albert Chong, Sarah Escoto, Abigail Lucien, and Hasani Sahlehe–all artists from the Caribbean diaspora. The gallery will also participate in the Armory Show with a presentation of works by Allana Clarke and Nathaniel Oliver. With busy summer and fall schedules, Freeman and HOUSING show no signs of slowing down.

Visit HOUSING on 191 Henry St, New York, NY 10002, Wednesday-Sunday 12-6PM.

You Might Also Like

As Deitch Cements Exhibition Curated by AJ Girard We Quiz Him on the Art of Self-Actualization

The New Art Advisory That Factors Artists Into Their Sales Process

What's Your Reaction?

Annabel Keenan is a New York-based writer focusing on contemporary art, market reporting, and sustainability. Her writing has been published in The Art Newspaper, Hyperallergic, and Artillery Magazine among others. She holds a B.A. in Art History and Italian from Emory University and an M.A. in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center.