Idelle Weber and Aurora Robson’s Environmental Works at Hollis Taggart

The impact of human activity on the environment is an unignorable fact. Everything we do affects the environment, from the trash we create to the carbon dioxide we emit while breathing. To live requires resources from the planet. While we can’t stop breathing, we can certainly address the material waste that humans produce. At Hollis Taggart, the current exhibition, “Remnant Romance, Environmental Works: Idelle Weber and Aurora Robson,” highlights this very subject. Photorealist paintings by the late Idelle Weber and a series of new sculptures by Aurora Robson that she made specifically for the exhibition address the subjects of environmentalism, consumerism, and waste. Through very different mediums, the two artists present poignant cases for self-reflection and join the larger dialogue on man’s role in the climate crisis.

While not at the core of her practice, Idelle Weber’s works in “Remnant Romance” fit solidly within the discourse on the human impact on the environment. Derived from photographs that the artist took herself, the paintings feature close-up still lifes of trash and debris in the streets of New York City and the East End of Long Island. Suzanne Weber, the artist’s daughter, said her mother would spend days photographing trash looking for the perfect subject. She projected these images in her studio and would sometimes even bring items back with her to have as a reference. What emerged was a body of work that is honest and, from an ecological standpoint, embarrassing. While people are removed from the paintings, their presence and their impact are undoubtedly felt. The trash, the crushed bottles, the dead birds, “remnants” as the exhibition title calls them, are all there as a result of human activities.

Much of the trash represented in Weber’s works relates to themes of indulgence and consumption. In “East End Bufferin,” she has painted a dead bird lying amidst leaves, flowers, and trash thrown on the ground. The artist has taken care to show the labels of various items in the scene, including the pain medicine Bufferin and a container from a lobster shell cracker. Next to the bird is a beer bottle and various pieces of plastic and metal scattered among the flowers and leaves. Perhaps the bird has died as a result of human activity, or perhaps it serves as a reminder of mortality. Whether a bystander or victim, the bird adds a somber reminder of the toll that human activity has on the natural world. While alcohol and medicine can be seen as analgesics, they can’t help to avoid the inevitable end both man and nature must face.

More than documentation of the detritus and waste cast off by human beings, Weber’s paintings act as evidence of material culture and the objects that surrounded their previous users. What is left is a memorial to the people who drank those beers, who ate that candy, who lived in a particular society at a particular moment. Ethnographic at times, Weber’s works are candid snapshots of the materials that made up the lives of their users. While there is certainly an element of critique–critique of mass consumerism, critique of waste–there is also an honesty to the works that deserves recognition.

In “Musical Chairs,” Weber has included a flyer for an independent film titled “Save Julian.” The flyer directs the reader to a fundraising website for the film that focuses on homelessness with LGBTQ youth. Reflecting an important social and health issue, the flyer represents the care and work of the people who originally made it. The ultimate fate of the flyer, crumpled and discarded amidst cigarette cartons and gum wrappers on the street, offers somber commentary on the life-cycle of social issues. Unfortunately, it appears the film faced the same fate, as the fundraising website reveals that the project received less than ten percent of its goal and was never produced. According to the artist’s daughter, Weber was not aware of the film, but she did purposefully feature the flyer in the painting because Julian was the name of her husband.

Archeological in a sense, Weber’s works depict the materials created and used by human hands. One painting underpins this concept with its title of “Poland Spring.” Showing food wrappers, cigarette butts, and crushed bottles discarded alongside dried leaves, the painting includes a visible label of a Poland Spring bottle. Both the bottle and the title are reminders of the natural resource from which the water derived. The work is a poignant representation of consumption and human’s taking for granted of the planet’s resources.

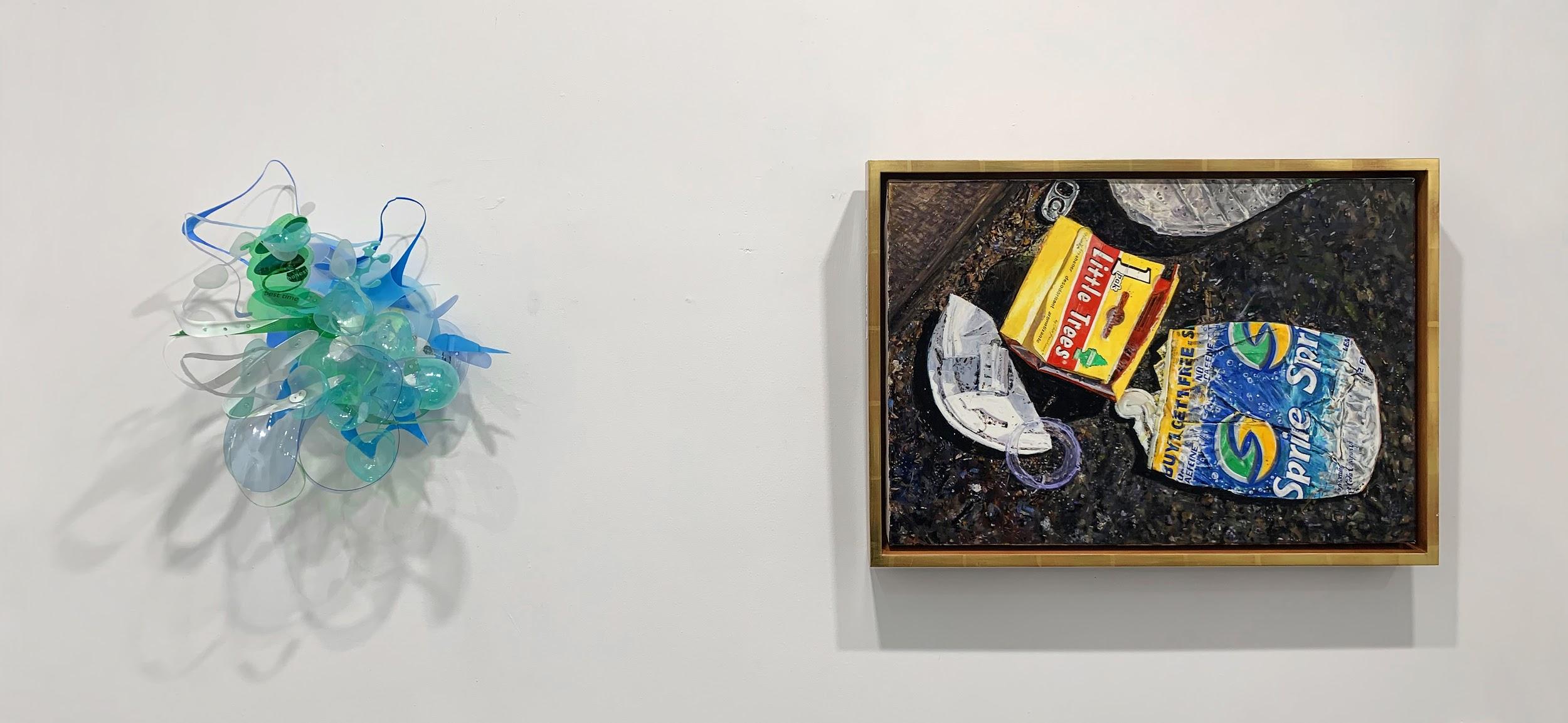

In conversation with Weber’s paintings are new sculptures by Aurora Robson that she made specifically for the show. Known for her use of discarded plastics, Robson pushes the boundaries of the material by cutting, weaving, reshaping, and reconnecting plastic strips, circles, and amorphous shapes into energetic sculptures. Organic in shape, the new sculptures for the exhibition take inspiration from the colors and materials of Weber’s works and appear to have emerged from the surfaces of the paintings themselves. In “Rational Optimism,” green and blue plastics extend from the wall in a small, delicate round burst. Installed next to Weber’s “Little Trees,” the materials in “Rational Optimism” appear as if they could have been taken right off of the painting’s surface.

While Weber presents direct evidence of humanity’s treatment of the Earth with paintings of trash, Robson addresses the subject with more contemplative sculptures made of the discarded material itself. While the use of found materials in art is far from new, the artist’s strong environmental agenda highlights its importance in her practice. Robson aims to produce works that do not generate additional waste. Though difficult and inherently limiting the work she is able to create, the artist explained this commitment: “It is a challenge that I accept with gratitude. I aim to reduce as much suffering and waste as possible through my work and life. I strive towards zero waste in my studio. This does dictate how I work — but I love having this as a common denominator and a principal in my practice. It is a pretty strict meditation – not incidental. My interest lies in softening the edges between nature and culture so that our presence is less of a burden on the planet and one another. My creative impulses are far less important than our two most valuable natural resources (water and air) both of which are being grotesquely sullied by plastic debris — so if I can satisfy my desire to make artwork while helping reduce and reuse a problematic toxic substance, all the better.”

Robson’s works in the show appear to capture moments of energy, as if they are moving, growing, and bursting through the gallery. The discarded plastics are bright and colorful with electric yellows, greens, blues, and purples swimming from wall to wall. Some materials she found on her own, and others people sent her from around the world, which the artist called bittersweet: “Solving this global problem requires multifaceted approaches – and so many people feel so powerless around it. Creative stewardship has potential to light up a pathway towards equity around this issue. Sometimes I work with materials collected by conservation groups who conduct clean ups of rivers, shores, and parks — other times with people collecting the material for redemption. I don’t discriminate in terms of where it comes from – as long as it is bonafide debris.” To prepare the plastics, Robson cleans and organizes the materials before she arranges them in her sculptures. The materials in the new works for “Remnant Romance” were assembled using ultrasonic welders, an injectiwelder, or stitched with an industrial sewing machine.

Unlike Weber’s very direct representations of human activity, Robson’s works remove the original hand that cast off the materials, and instead repurposes waste as a medium for beauty and contemplation. However, that is not to say that the hand of the artist is not present. Indeed, Robson’s careful reworking of the plastic pushes the boundaries of the medium as she gives life back to the discarded materials.

In a shift for Robson, two works in the show take on the form of functioning objects: both “Doughnut Economics” and “Plantpocalypse” incorporate headgear with the artist’s old metal welding hat in the former and a found hard hat in the latter. “Plantpocalypse,” which was named by Robson’s daughter, is a green, hive-like mass with undulating plastic strips that encircle the piece. The whole sculpture sits atop a hard hat that can be worn or displayed as a sculpture. Cheery and energetic, the colorful work belies the origin of the discarded plastic materials.

While waste is at the forefront of both artist’s works in the show, there is an undeniable beauty and elegance that weave through the exhibition. From the colors and sensual curves of Robson’s sculptures to the flowers, pristine ribbons, and poetic tribute to her husband in Weber’s paintings, there is harmony and beauty that moves from one work to another.

In many ways, the works in this exhibition should not exist. They exist as a result of the human consumption that occurred to introduce the materials into the waste stream. However, what could be an exhibition that is moralizing and patronizing is instead thoughtful and sensitive. Waste is inevitable. The works in this show offer a moment to reevaluate waste and reframe it as an opportunity for self-reflection and a celebration of the creative possibilities of the materials we discard.

“Remnant Romance, Environmental Works: Idelle Weber and Aurora Robson” will run through February 20, 2021 at Hollis Taggart, 521 West 26th Street.

You Might Also Like

‘Galleries Commit’ Envisions a Greener Future for the New York Art Scene

Physicality: Negotiating Place/Site/Geography in Art During Lockdown

What's Your Reaction?

Annabel Keenan is a New York-based writer focusing on contemporary art, market reporting, and sustainability. Her writing has been published in The Art Newspaper, Hyperallergic, and Artillery Magazine among others. She holds a B.A. in Art History and Italian from Emory University and an M.A. in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center.