‘Las Vegas or Bust’ and Other Li Jin Works in Clever Series of Display at Manhattan Apartment Gallery

Chinese contemporary ink artist Li Jin is strikingly unpretentious. At his 2012 and 2022 institutional surveys, respectively at Today Art Museum, Beijing, and He Art Museum, Foshan, Li Jin shied away from the rigorous theorization that is usually required of a late-career museum survey and opted instead for showcasing his acutely mundane yet precise observations of everyday life—food, sex, and gatherings. Unlike his generation of Chinese contemporary artists who entered the West through cynical realism and the Chinese reading of Dada, Li Jin retreats from grand narratives of political protest and history-making and finds solace in portraying daily life as a social practice. At the He Art Museum survey Meat Eaters Aren’t Superficial, Li Jin’s works from the Morning Exercises series were featured prominently. In creating the series that spans several years, Li Jin wakes up during day break and liberally and uninhibitedly uses ink to sketch out personal matters. The embodied body that demands pleasure and nourishment becomes a fleeing impression that can only be temporarily (re)captured in Li Jin’s vivacious trails and pours of ink. In them, Li Jin commits to the messiness of existence with a psychologizing bent that surfaces forgotten confessions and repressed affects. Casual yet profound is Li Jin’s signature style.

In his most recent exhibition, actually a series of them, dealer Jeffrey Liu, who runs an intimate gallery in his Gramercy residence, leans into Michel de Certeau’s ‘practice of everyday life’ as he presents selected works from the ink artist’s Morning Exercises series. To accommodate the experience of viewing Li Jin’s works which is never linear, Liu’s presentation follows a casual format—rotating works every few weeks, without the fanfare of a new press release. Visitors who return will happen upon the next iteration of the exhibition. By dividing the works into various chapters—loosely organized around urban dwelling, spirituality, and landscape tradition—Liu creates a narrative where works complement, contradict, and extend each other without settling conclusively on a final effect.

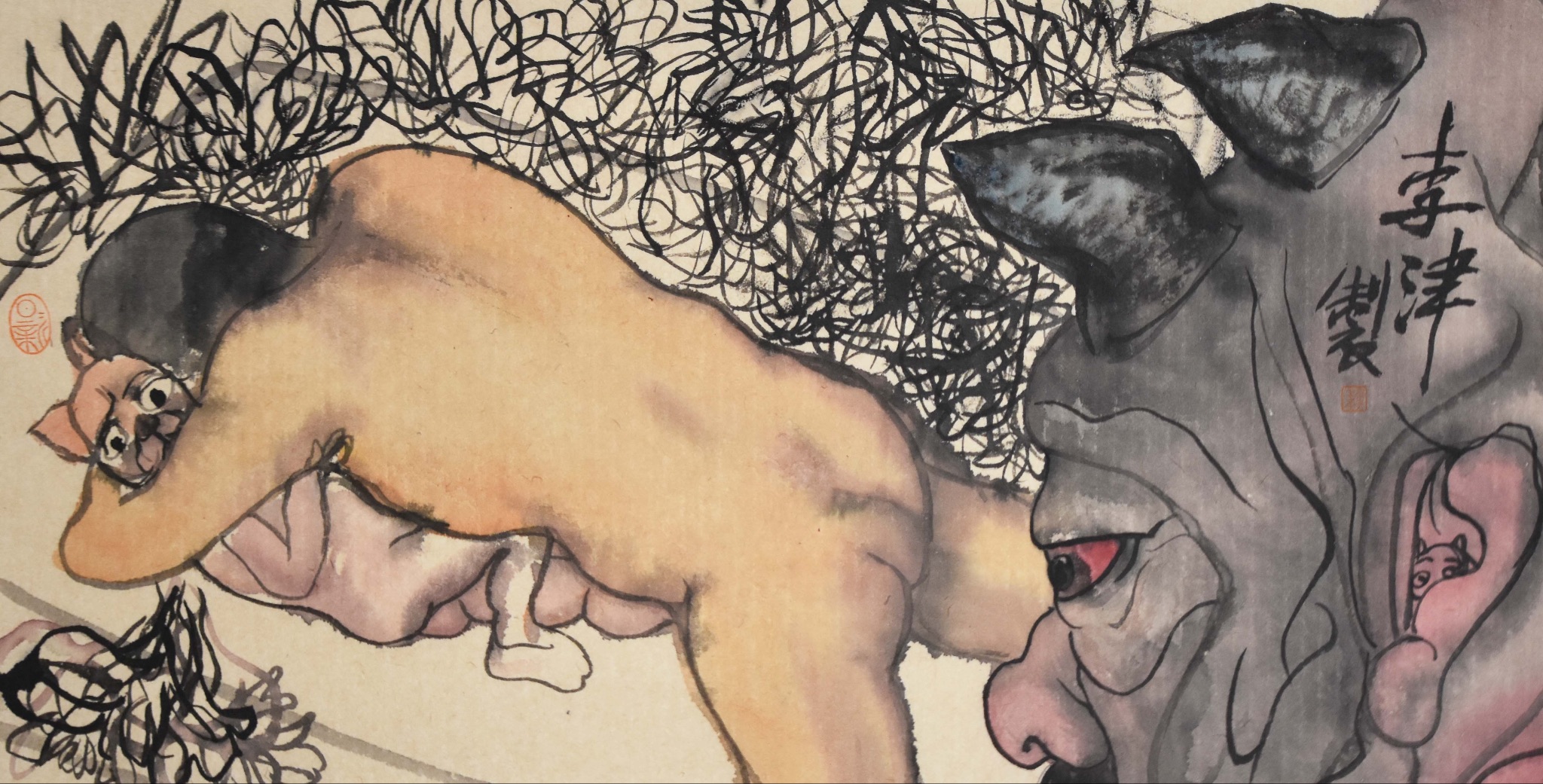

From October to November, Liu exhibited the initial iteration In the Mundane, which traces subconscious undercurrents of needs and wants, which often manifest in rituals of communication that never quite come full circle. For example, in Crow Language (2023), a confused man (could he be the artist himself?) confronts a vocalizing bird in an attempt for mutual understanding to no avail. Elsewhere, in Dream Demon (2020), the Gauguinesque psychosexual drama of lost innocence, compulsions for returning to the original, and unleashing unpredictable forces of an uncontaminated nature goes on full display. Against a timeless mess, a man, sound asleep, lies atop an anthropomorphized canine and exposes his naked bottom. Is the cross-species liaison between the two illusory or real? The answer is uncertain. The helpless gaze of the subjugated animal meets that of a red-eyed demon piercingly awaiting the opportunity to prey on them, which may never arise considering how fragile nightmares are. Lover (2022) pays tribute to Pop, famous for its portraits of women sourced from images in mass media. However, here Li’s stylish woman, staring at an unknown object of affection outside the frame, seems more disoriented than absorbed in the glamours of self-fashioning. Moment of Calm (2017) continues the Pop tradition of deploying larger-than-life texts, yet seems indecisive on which kind of reverie, sexual or otherwise, is being enjoyed. Sexuality again puts a full-frontal assault in When Will You Return (2019), which presumably depicts the mise-en-scene of escorts courting their clienteles. The pair to the left strikes me as an unsuccessful transaction, with the male patron turning his back on his temporary lover, uninterested in a second meeting. The pair to the right, in the middle of a flirtatious dance, offers no clue as to the fate of their coupling, as all I can access is the man’s aloof facial expression. Most notably, the two pairs pay no attention to each other as if they belong to different worlds. Focusing on moments of affective excess found in urban life and their many unwarranted permutations seeping into our perceptions of the material reality, In the Mundane documents the grey zones of contemporary dwelling, all the more mudded by the heaviness of being, sometimes humorous, and sometimes absurd.

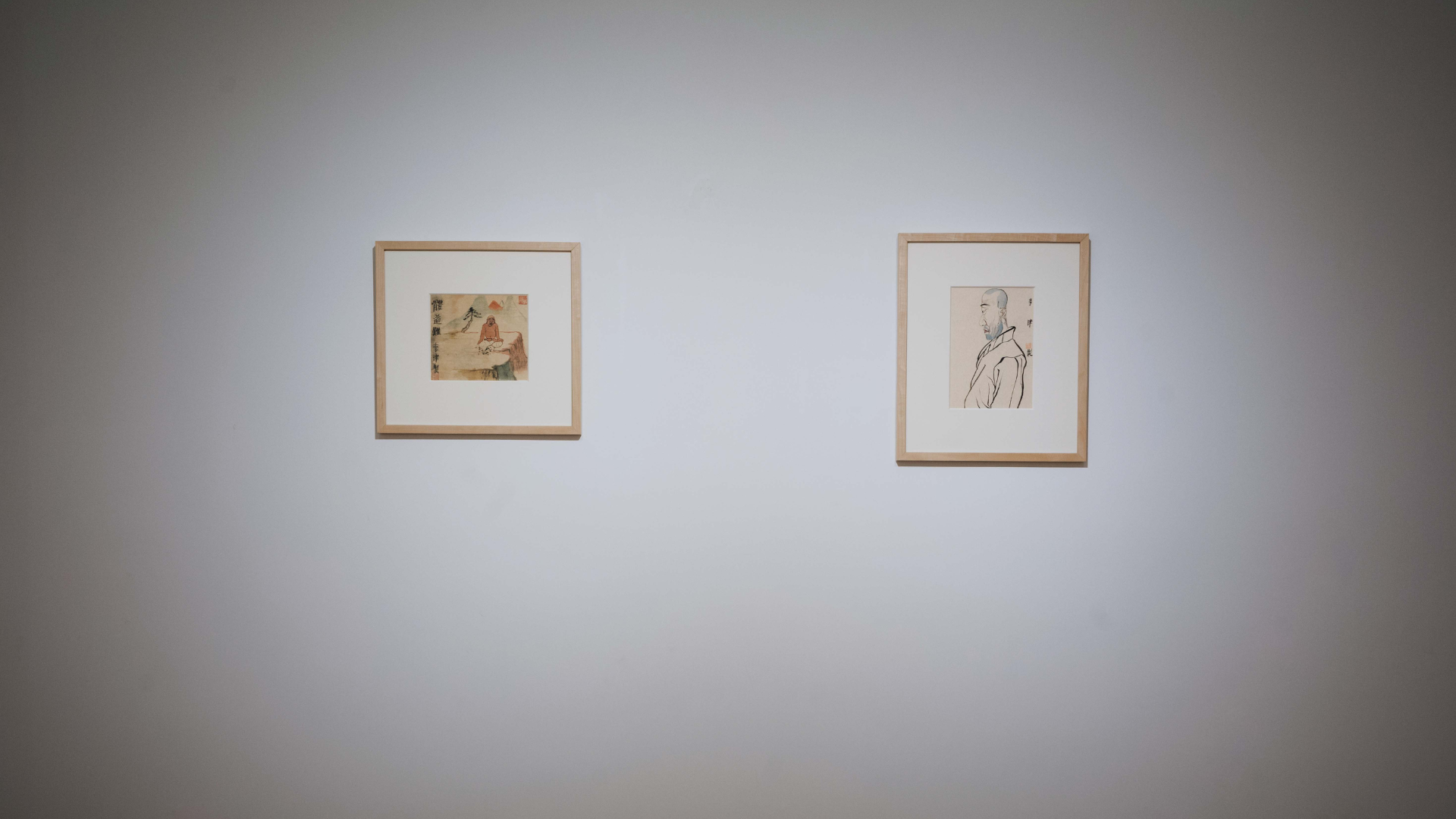

From November to January, for its second iteration Out the Spiritual, Liu exhibited highly introspective paintings made during Li Jin’s pandemic-era stay at Guoqing Temple in 2022. Li Jin employs aerial, breezy, and lightweight brushstrokes toward spiritual concerns, resulting in a melancholic yet witty depiction of self-discovery and its failure. A frustrated monk who is partially based on the artist himself is a recurring figure in the exhibition, whose spiritual commitment is a process rather than a required destination. For instance, the contemplative figure of Monk (2022) does not seem enlightened but rather weighted down by the burden of living through a laborious life that supposedly leads to enlightenment. Plausibly these ink studies of far-from-ideal monks mirror Li Jin’s experience of living amongst the now professionalized monks at Guoqing Temple, a historically significant spiritual site that has transformed into a complex of cultural products for secular tourists, in a politically turbulent time. Pains of Dao (2022) similarly confirms the precarity of enlightenment in modern times. A dispirited monk has cut all of his hair out with the hope of becoming closer to the next milestone of his spiritual journey only to find himself still far from such a goal. The conundrum of enlightenment reaches its affective height in A Poet’s Expressive Scroll (2022), which pays homage to the celebrated exiled poet Qu Yuan of ancient times, canonized in Chinese literati culture as a symbol of the politically impotent yet wise scholar-officials. The tale of his noble suicide in the aftermath of national catastrophes lends itself to varying interpretations of allegiance and dissent. In A Poet’s Expressive Scroll, the Qu Yuan-adjacent figure also looks troubled by the free will of choices, unsure if the limit of his intellectual achievement lies in this life or the next. Such is the central theme of Out the Spiritual: the circular search of enlightenment in the present age.

Last weekend, I visited Liu again to see another four Li Jin works from a series commissioned by Sotheby’s Los Angeles in 2017. Drawing from images and memories of his grand tour of the United States, from New York to Las Vegas, Li Jin takes a more painterly direction in this body of works, fleshing out the affinity between Chinese ink art and historical avant-garde movements. The lush and breathy strokes of Las Vegas or Bust (2017) gesture toward giants of German expressionism, such as Max Beckmann and Otto Dix. Fun in the Snow (2017) reminds me of the expressionists in interwar Vienna with its bold and overt use of sensual color and patterns and unruly and condensed figuration but updates its psychological depth with an appreciation for the multiplicity of racial and cultural subject-positions in New York City. Still, the diverse mixture of influences here does not make these works any less homely. Spring Snow in New York (2017) strikes me as a quintessentially Chinese picture, for its assimilation of Chinese landscape painting (shan shui hua) traditions.

As I write these words, I eagerly anticipate what comes next for Liu’s careful connoisseurship of Li Jin’s practice. During each chapter, I was able to witness a different front of Li Jin’s humorous and incisive observations of contemporary life in China, where distinctions between high and low, secular and spiritual, ancient and modern have long collapsed. What more glories of everyday life can be revealed, in all its fullness of aspiration and melancholy, success and failure, and desire and despair?

You Might Also Like

Growing Pains: Anna Ting Möller’s Symbiotic Sculptures

What's Your Reaction?

Qingyuan Deng is a curator and writer, based between Shanghai and New York City. He is interested in relational aesthetics, experimental filmmaking, and the intersection between literary culture and visual arts.