Subtlety and Reconsidered Borders Reign in the Whitney Biennial 2024

Even Better Than The Real Thing is subtle, leading with sonic elements and works that embrace the passing of time by artists not exclusively from or living in the U.S interrogating themes that dominate contemporary art discourse: ecological disaster, reproductive rights, lgbtq+ rights, settler colonialism, and indigenous activism and indigeneity—but, not in a violent manner. Subverting land acknowledgments, indigenous Portland-based artist Demian DinéYazhi’ leads by example. Their neon poem, facing the Hudson River, we must stop imagining apocalypse / genocide + we must imagine liberation(2023) expresses the ethos of the exhibition. It is not remarkable or unique in its form, neons are pervasive, but as a call to imagine liberation above extractivism, fascist governments, and torture it is a beautiful, powerful, and necessary reminder to visitors of their agency in change. Most works in the biennial have this gravitas, they are not in-your-face urgent, but they are persistent. Like, U2 in their song Even Better Than The Real Thing (1991) lyrics beg for one, two, and even more chances, promising each time will be better, artists in the 81st Whitney Biennial will not give up on forging a better future.

Through embedded flickering letters, DinéYazhi’s piece also reads: “Free Palestine.” First Artnet and The New York Times reported on the hidden message in DinéYazhi’s poem, then others followed. Except for the firing of David Velasco and its aftermath, which was widespread, Hyperallergic is the only art publication that consistently reports on pro-Palestinian actions by artists and subsequent institutional pushback. On November 11, following his last Performa commission Enter Exude,Teo Ala-Ruona and his collaborator explained to the audience that the Performa team had denied their request to end with a pro-Palestinian message. Other museums have removed work and chastised members of the public for expressing pro-Palestinian opinions. In the 2017 biennial, at the height of conversations about race, Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmet Till sparked so much debate, ire, and discord that management at the museum took it down to then put it back up. DinéYazhi’ message has not been met with public pushback and curators Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli have backed the artist, and management at the Whitney has issued a statement confirming that the work will remain on view. With even U.S. President Joe Biden calling for a ceasefire it is time for institutions to let artists express their pro-Palestinian opinions openly.

Overall, the curators have excelled in creating dialogs between works, leading the visitor through the exhibition. On the 6th floor, in Ricerche: four (2024) Sharon Hayes interviews three groups of LGBTQIA elders as the last in a four part series of a decade long investigation into sexuality and gender in the U.S. Following the same aesthetic and line of inquiry, the previous iteration, Ricerche: three (2013) where Hayes interviewed thirty-five Mount Holyoke students debuted at the 55th Venice Biennale The Encyclopedic Palace. The other two interview children of queer and trans parents and players on two women’s tackle football teams. Hayes fashioned the group conversations after the 1963 film, Comizi d’Amore (“Love Meetings”), in which the filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini moved across postwar Italy interviewing Italians about sex and sexuality, examining the shifting values of the period. In four gender appears as performative. Malleable, and governed by society and Hayes’s thorough inquiry brings a scientific dimension to the work. Sharing the space gallery is Carolyn Lazard’s Toilette (2024) stainless steel medicine cabinets denoting back ‘his and hers’ and infrastructures of self-care. Representing the instability of support, Paloma Blanca Deja Volar/White Dove Let us Fly (2024) Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio’s oblong block-like sculpture in beautiful marbled gradients of fire-y orange and brown amber, lifted off the floor and held in place by metal supports, will melt in the sun. Amber, or resin, forms in trees to protect gashes and or breaks in bark, often caused by chewing insects. By embedding copies of archival documentation from activist practices Aparicio’s work speaks to the necessity for continued maintenance, and slow processes of growth, breakage, and repair. Finally, Kiyan Williams impressive compacted earth sculpture Ruins of Empire or The Earth Swallows the Master’s House (2024) of the White House on its side speaks to the erosion of institutions but also nods to generations past who have worked the land (slaves, immigrants, and U.S Americans) and where they are now—growing and grounded in the earth of the United States. Steps away, an aluminum sculpture of the transactivist Masha P. Johnson watches over the White House. These four works create an interconnected conversation of how people engage with, or exist alongside institutions and their policies.

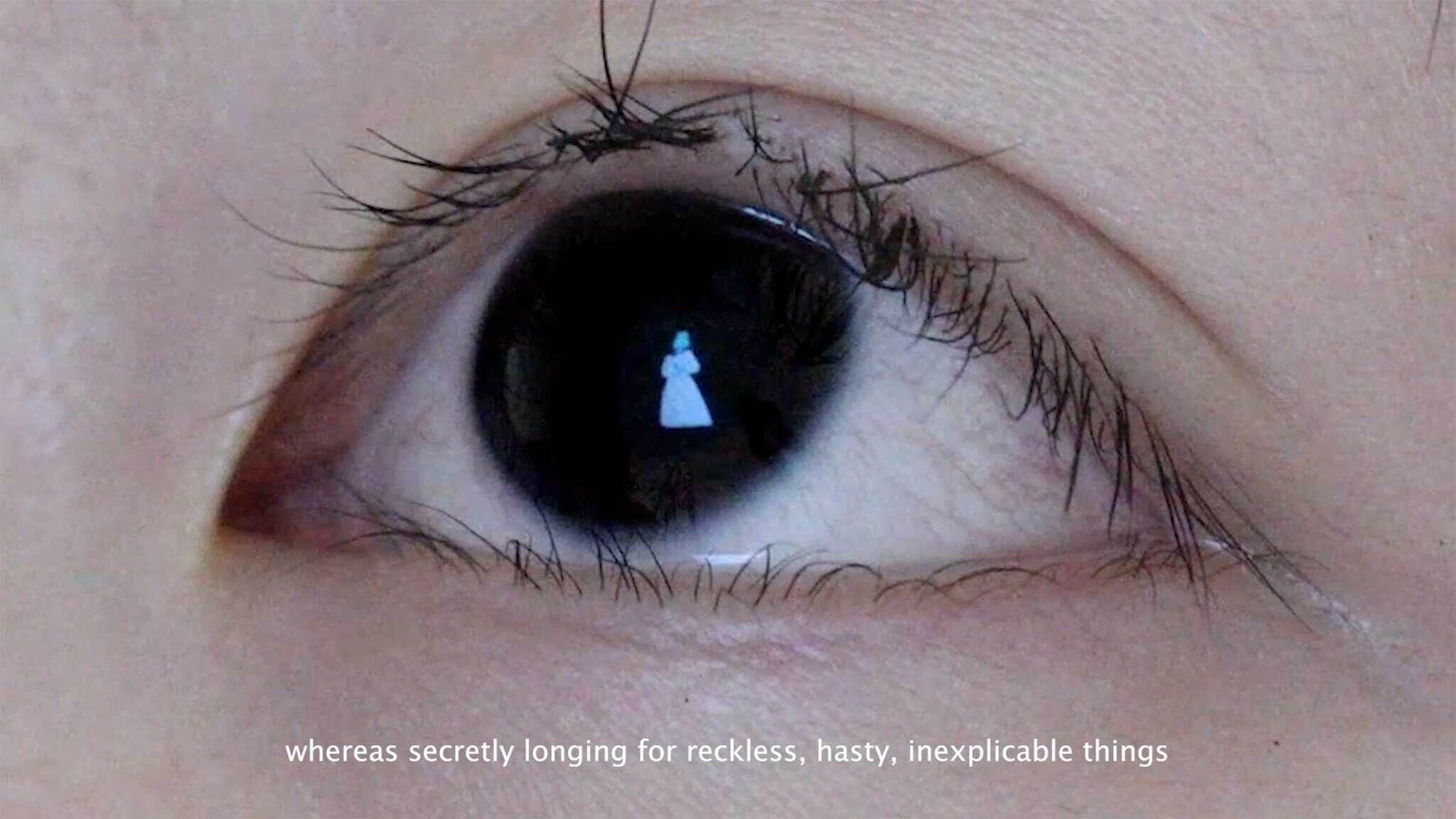

On 5th floor, Toumaline’s video work Pollinator circles back to Johnson, it is based on their archival research—a funerary march, flowers in the sun, is part of the footage in this disjointed video that seeks to create an emotional response. In another archival reenactment, in his regular dramatic and poetically opulent manner Isaac Julien revives the work of Alain Locke (1885–1954), philosopher, educator, and cultural critic of the Harlem Renaissance (played by André Holland) in Once Again . . . (Statues Never Die) playing on five screens amongst sculptures by Richmond Barthé (1901–1989) and Matthew Angelo Harrison (b. 1985). It is a meditation of black aritsts’ legacies. Shifting gears from reviving and honoring, Diane Severin Nyugen’s red screening room with comfortable seating to lounge on the floor offers a space for the body to rest as Her Time (Iris’s Version) follows an actress playing a role in a historical film about the Nanjing Massacre of 1937. It is shot in the world’s largest film studio, China’s Hengdian World Studios, a major stage for the production of historical films. The piece investigates girl- and womanhood and how history and events are retold, complicated by segments where fiction is confused with reality. Screening to the public on June 21, Yasmin Anlan Huang’s 5:31 min video poem Her Love is a Bleeding Tank (2020) focuses an unblinking eye with a computer-generated overlay of a white shape dancing in its iris and a voiceover retelling a teenage memory—the poem beautifully evokes love, disappointment, and overcoming emotion. These artists offer different entry points into narrating history.

Further along, a nook has three works by Harmony Hammond Patched(2022), Chenille #11 (2020), and Black Cross(2020-21) which texture use of cotton grids, and material play evoke knitting, bedspreads, and other material culture while extending the language of Arte Povera and Suprematism (most notably, the cross referencing Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square, 1915) to American female dominated domestic material culture. Offering a tactile element to Carmen Winant’s The Last Safe Abortion a towering wall piece comprised on 2700 photographs of women both accessing and protesting to preserve the right to abortions, and the day-to-day at health clinics that provide them since Roe vs. Wade was overturned. Hammond evokes women making and Winant evokes women’s rights to their bodies, both through striking visuals.

In a mesmerizing video work, Tray Tray Ko (2022), Seba Calfuqueo, traverses a lush landscape moving through bush, river, and waterfalls in the South-Central region of Chile and Argentina observing its natural and spiritual power, historically the Mapuche people have lived there for thousands of years—her body serves as the only trace to this fact. Similarly, to Ana Mendieta’s ‘earth-body works’ (1972-85) Calfuqueo’s body becomes sculptural in the landscape, she does not like Medieta who dug with her hands in the creeks and on the land, in and around Cedar Rapids, Iowa—the spiritual connection with the land remains the same. Calfuqueo’s work positions her body not important to the landscape, but that the landscape is part of her body.

Counterbalancing DinéYazhi’s installation, Claire Tossin’s Pre-Columbian Mayan wind instruments are installed behind glass in a black box installation—-as they are 3D printed recreations this mode of exhibiting them that replicated museological practices is a bit drab. An accompanying film however, shows the pieces being played with footage from Guatemala and John Sowden House in Los Angeles, built by Frank Lloyd Wright Jr. in the “Mayan Revival” style, which the artist critiques. With its placement this work becomes a clever response to DinéYazh poem’s call for imagining liberation, but its drab display missed the mark, as well as the critique on appropriating Mesoamerican motifs—pastiche in architecture can be honorific.

Occupying a room, Nikita Gale, who often works authorship and the body in relation to sound, has silenced the keys of a self-playing piano to instead amplify the sound of its mechanism in TEMPO RUBATO (STOLEN TIME). Further investigating that which lies adjacent, Gale has worked with the licensing organization ASCAP to question whether or not it still constitutes licensing, locating the legal definitions of authorship. In the stairwell, Holland Andrews’s work Air I Breathe: Radio emits manipulated sounds harmony, dissonance, and melodic sounds created with a pedal-operated effects processor. According to the wall-text, “receiving information on multiple channels, as if the mind were switching stations on a radio,” it reminded me of a 90s video game with musical elements indicating the characters’ actions.

Biennials are not only a showcase of artists, but also for curatorial practice: experimentation, trend-setting, and rule-breaking. Iles and Onli’s artists are mostly from or living in North America with some exceptions, Calfuqueo, an indigenous artist from Chile, and Dominican-born London-based artist, Ligia Lewis, whose video work is about the transatlantic slave trade on view in the galleries—land, indigeneity, and the slave trade tightly relate to an American experience. In addition, Asian and indigenous, including Sápmi, artists are numerous in the video program. Remarkably, Iles and Onli’s inclusion of non-North American artists transcends the concept of borders entirely; indigenous communities often live beyond imposed borders that do not pertain to their culture, Sápmi lands extend through Finland, Sweden, and Norway. While Bangkok-born Korakrit Arunanondchai’s film program Dear Ghost Is a Memory is False Does it Mean It Does Not Have Real Consequences? presents Asian artists work in response to Western modernization. It is not the first for curators to explore the territorial and cultural understanding of “America,” which, as the word denotes, extends beyond the United States. David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards’s 2022 biennial, Quiet as its Kept, had a sub-focus on the U.S.-Mexico border with artists from the border city Tijuana and others from Mexico City. Mostly co-curated by Whitney Biennial in-house curators, it is the third time Iles co-curates the biennial (2004, 2006, and 2024)—versed in the magnitude of the exhibition and its mission to showcase American art it is perhaps her experience that has allowed this edition to emerge as sophisticated and subdued.

Curatorial experimentation comes in many forms, in 2014, three outside curators were responsible for one floor each and presented over 100 artists. In 2012, the first biennial I saw, curators Elisabeth Sussman and then-independent curator Jay Sanders (who was later hired) interrogated curatorial practice by inviting artists to curate smaller shows within their exhibition. Both of them great showcases, in their different ways. Even further back, in 1975, curators made the bold move to respond to critique of the art market’s growing influence by selecting artists who had not had a New York show in the past ten years, and never at the Whitney, it was trashed by critics.

The 2014 biennial featured Zachary Drucker’s intimate and vulnerable documentary photographs of her male-to-female transition alongside photographs of her partner, Rhys Ernst, whose video work was also on view, female-to-male transition. Drucker, also a transactivist, went on to produce the Emmy-nominated docu-series This Is Me and consult on the TV series Transparent, and is returning to curate the biennial’s film program screening on July 12 alongside Greg de Cuir Jr. (April 12, September 20), sinnajaq (May 3), and Arunanondchai(June 21, this session includes Anlan Huang’s work). Brooklyn-based Taja Cheek, aka L’Rain, will curate five performances (April-August). These programs will make the biennial even better.

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than The Real Thing is on view until August 11 at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

You Might Also Like

The Immigrant Artist Biennial’s Central Exhibition Relocates Regional Tensions

Survival Kit 9: Exhibiting Radical Solutions For Society’s Survival in Latvia

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.