The Immigrant Artist Biennial’s Central Exhibition Relocates Regional Tensions

As part of The Immigrant Artist Biennial 2023, “Conflictual Distance” opened at EFA Project Space amid global challenges that necessitate empathetic responses and meaningful action. Transgressing perceived geographic limitations, the show relocates regional tensions in a “foreign” context, proposing new possibilities for them to be seen and understood by people who may or may not have first-hand experience with these struggles. Mobilizing a sense of emotional and physical immediacy, the works included in the exhibition address issues such as the power of mass media, representation, and generational trauma, in order to facilitate mutual understanding through a glocal lens.

Serving as the biennial’s central exhibition “Conflictual Distance” presents the work of Golnar Adili, Marcelo Brodsky, Pritika Chowdhry, Erika DeFreitas, Maria Kulikovska, Keli Safia Maksud, Mila Panić, Jovencio de la Paz, Emilio Rojas, Nida Sinnokrot, Slinko, and Rafael Yaluff. The exhibition is on view at EFA Project Space until January 6th, 2024.

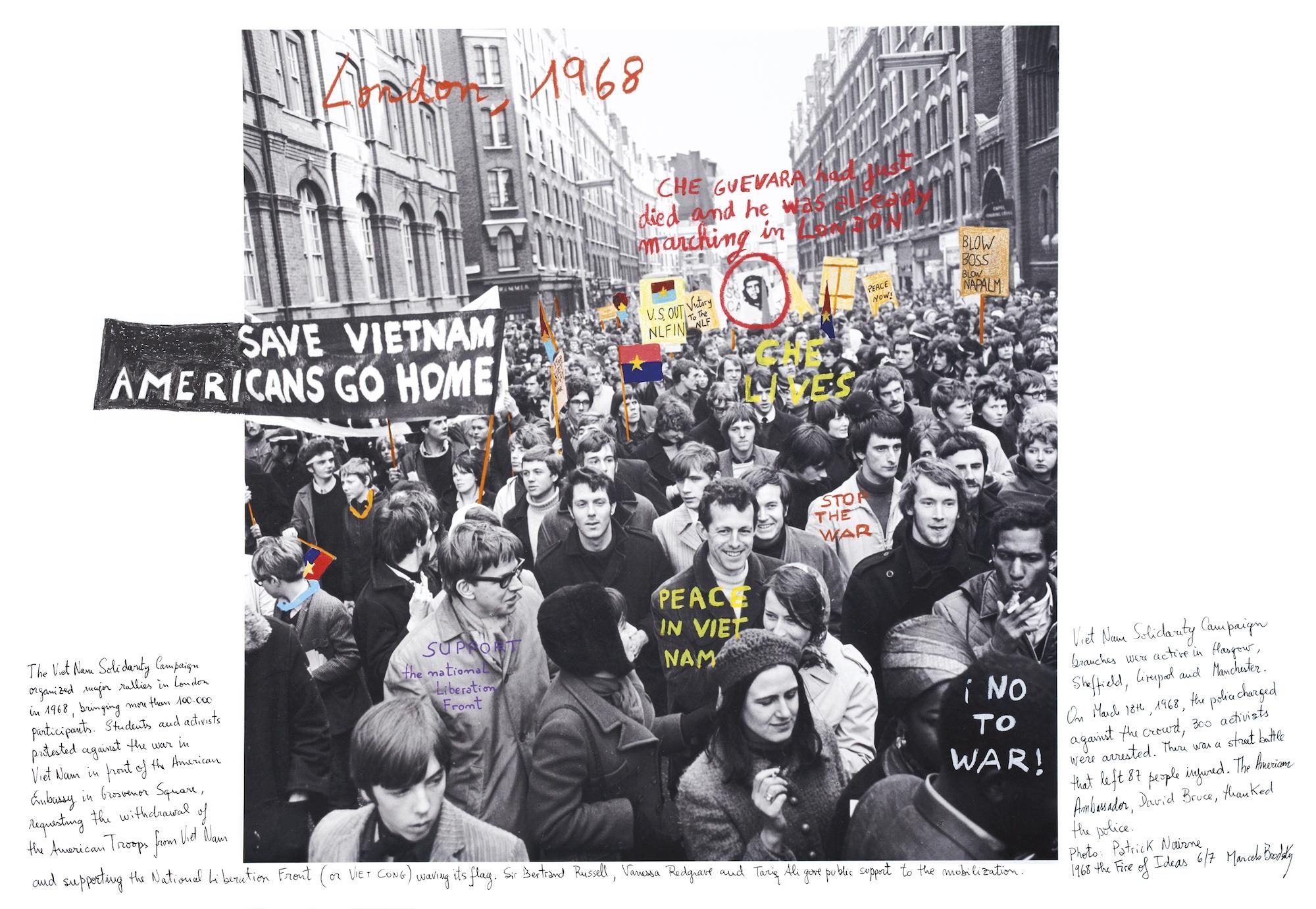

Among the most compelling works were Marcelo Brodsky’s overwritten photographs of historical protests—a semi-archival practice. The locations, dates, major figures involved, and even slogans are specified to provide context; anonymous faces and bodies form collective instruments of justice. The series titled “1968, The Fire of Ideas” taps into the particular year’s climate of activism against the perpetuation of warfare and ongoing human rights violations. Situating demonstrations as a linkage across continents, Brodsky shows how the ideological zeitgeist of 1968 had directly negated geographic borders, forming a transcontinental connection among cities such as London, Montevideo, Kingston, Washington, and Rio de Janeiro, to name a few. In this way, the series effectively points out the relational nature of historical events and uprisings, highlighting the invalidity of the “global vs local” as a dichotomy. Additionally, a contemporary viewer is likely to be reminded of similar contentions or events close to when they engage with the work. In this way, Brodsky reveals how parallel socio-political actions exist across both time and space.

The exhibition also intimately shows the plasticity of individual bodies. For instance, Erika DeFreitas’s video, “Her body is full of light (often, very often, and in floods),” documents the Guyanese artist and her mother in front of a white wall. As their countenances go from serene to ecstatic to being drenched with tears, they reenact not only “Catholic traditions of lamentation” but also childhood memories and colonial trauma. Revealing how a multidimensional past can translate to people’s everyday expressions, these cathartic, passionate outbursts oscillate between ritualistic performance and emotional purging. In Maria Kulikovska’s watercolor drawings, bodies are gendered, sexualized, mutilated, and weaponized. Shades of mauve and blood red evoke the colors of bodily tissues and their forensic vulnerability. According to the artist’s website, pieces from the series “My Beautiful. Wife?” were developed in the spring of 2014, “just after a phone call by the artist’s dad about the outbreak of the occupation of the Kerch city”; the title of the series “888” stems from number 8’s recurrence in key aspects of the artist’s life, one of which being that her place of residence in Kyiv was 888 km away from her lost family house in Crimea. These bodies, therefore, become sites of resilience and silent confrontation against the backdrop of war, exile, and violence.

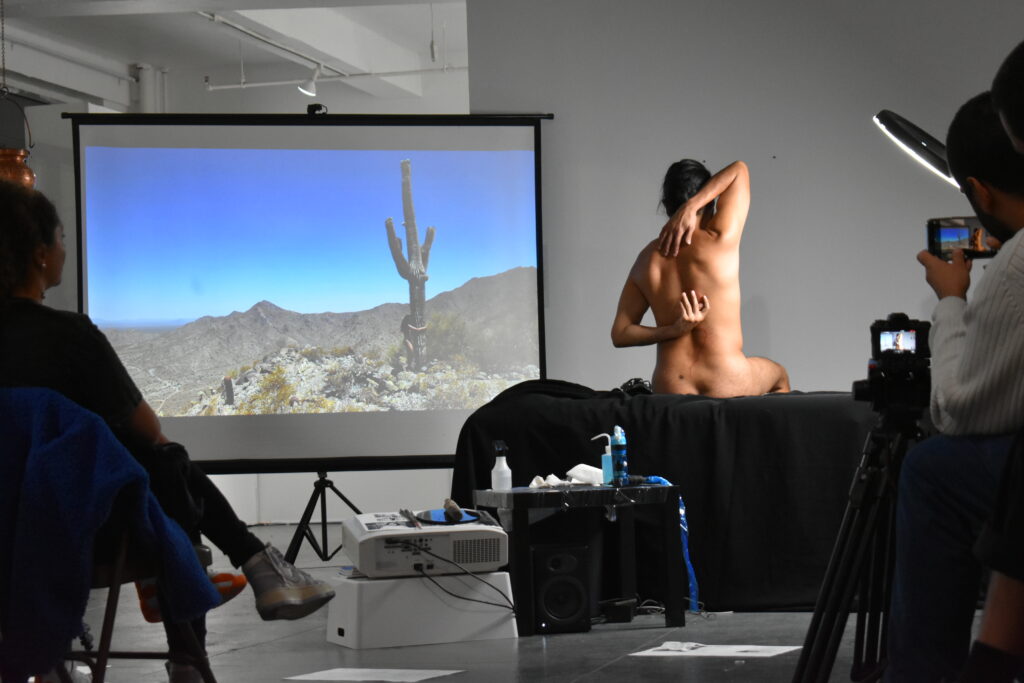

The embodiment of collective trauma onto individual bodies is further exemplified by the performance “Open Wounds: A Gloria,” presented by queer indigenous artist Emilio Rojas on December 9th. As Sujetka Val Terkes dry tattooed the outline of the US-Mexico border along his spine, Rojas clenched in his mouth Gloria Anzaldúa’s 1987 book, “Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza” as a tribute. Like Anzaldúa famously wrote: “The US-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds,” the performance sought to reveal the distress and visceral sense of hurt experienced by migrants. It also incorporated audio narrations, as well as a video background that included a clip of the artist hugging a spiky cactus without clothes on—the vulnerability of the human body on a contended piece of land. The performance became increasingly painful to watch, as his skin near the open wound started to become redder and more swollen. His pain—part of a collective pain—was silent but made visible: his toes curled, his calf muscles tensed up, and his back muscles squeezed towards the spine. I felt almost guilty sitting in the audience and looking on.

In fact, the performance coincided with NYC’s annual SantaCon, a Saturday when festive crowds saturated Manhattan. Christmas songs from the streets faintly lurked in the background and, inadvertently, syncopated the performance’s soundtrack. As I headed home afterward, I was greeted by pro-Palestine protesters that flooded the streets the moment I got out of the subway. The two consecutive encounters generated a near-satirical tension that seemed to echo the main themes of the show. The city felt disorienting—a timely reminder of the many walks of life that can simultaneously exist in one microcosm. What difference, then, does distance make?

“Conflictual Distance” is a humbling exhibition that opens up pathways for further learning. From Slinko’s video documentation of a Ukrainian flea market struggling to fully purge Russian influences, to Keli Safia Maksud’s dissection of how national anthems interact with structures of power, or to Nida Sinnokrot’s video installation demonstrating how politicized media outlets tactfully manipulate public opinions, this show encapsulates the participating artists’ scrupulous research and ardor for storytelling. Bodies, landscapes, and pictorial memorabilia find themselves telling localized stories with a universal tenor. With an informative exhibition like this, I am learning to see—with eyes and heart wide open.

Art Spiel and Cultbytes are, for the second time, proud media sponsors of the biennial, and this review series is published as part of TIAB’s writer’s residency generously supported by Lesley Bodzy Studio and Fraser Birrell Grier, Esq.

You Might Also Like

A Workshop on Love and Afropresentism with Neema Githere

Despite Tense Relations, A Pro-Ukrainian Video Art Platform Stages its 29th Program

“Parasites and Vessels” Conveys the Resilience of Immigrants

What's Your Reaction?

Xuezhu Jenny Wang is a multilingual translator and content creator. In addition to writing about postwar and contemporary visual culture, she is working on a research project that focuses on mid-century interior design and mechanization.