A Window into Lu Yang’s Ultimate Creation

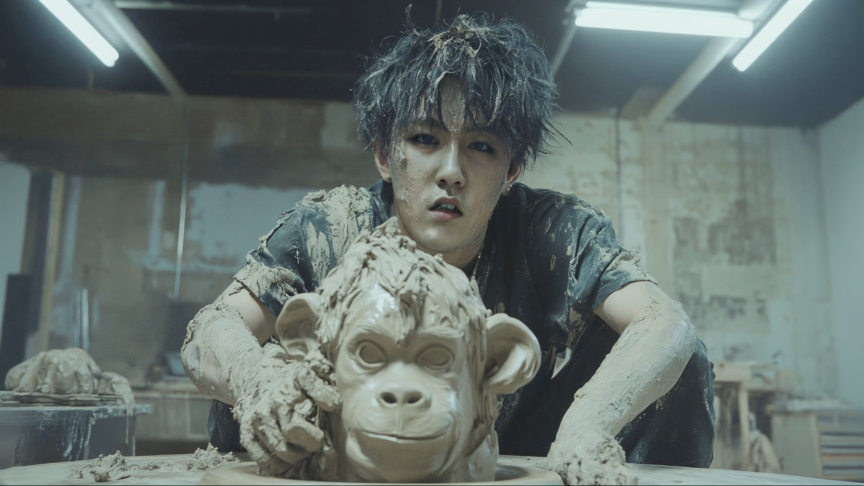

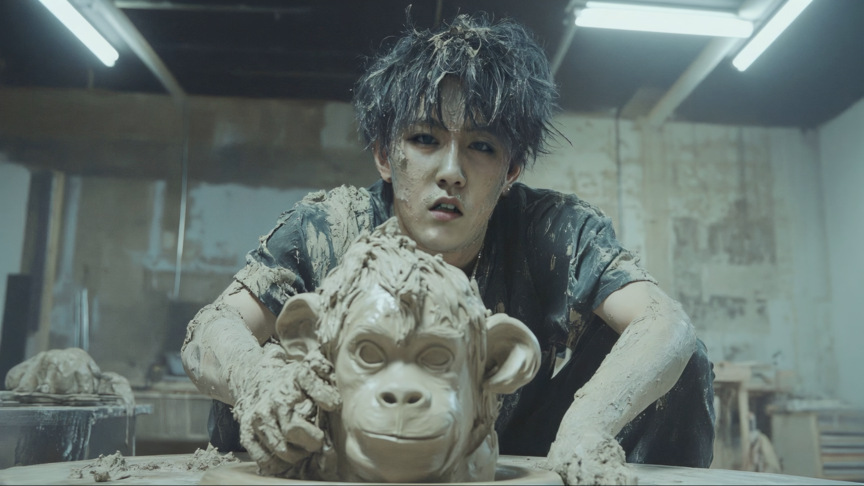

Multimedia artist Lu Yang is not weighed down or controlled by technology; refreshingly, he sees technology as a tool serving his own expression. His newest exhibition DOKU! DOKU! DOKU!: samsara.exe at Amant in New York centers on the endless possibilities and identities of DOKU, an avatar based on himself. Probing life’s most important questions against dramatic, jarring, and often disturbing scenery, three films from the series are on view. Since my first encounter with his work in 2015, I have continued to be both surprised and captivated by its evolution. Maybe it is the combination of his online, IRL, and spiritual plane existence that lends Lu’s explorations of identity and our world an unusual air, and that he borrows more from Buddhism, pop, and game culture than art history. To make these films Lu primarily used Unreal Engine, together with various AI tools, but more than form what matters, he writes to Cultbytes, “is always the inner philosophy and creative logic of the work.”

Certainly, artists who spend much of their time in the digital realm are also those who engage with its native tools in the most complex ways. Lu has continued to develop and showcase his ideas through commissions and exhibitions at leading institutions on the global stage—from the Venice Biennale to Times Square’s Midnight Moment—over the past decade. Watching DOKU–The Creator, at my laptop ahead of the opening, the series’ current final chapter, I was reminded of lucid dreaming and of Satoshi Kon’s Paprika (2006), in which one of the characters’ avatar runs, flies, and transforms through shifting dreamscapes that visualize the paradox of control within instability. Rather than Freud’s model of dreams as the return of repressed desire, Yang’s work resonates with a Jungian framework, where archetypes and cultural symbols surface in amplified form.

The Creator renders the digital realm as the ultimate lucid scape: a controlled environment that nonetheless slips into darkness, where bitcoin logos rain from the sky, Lu’s avatar drifts through high-rises and deserts, and a narrator expounds on consensus, value, and ownership in art. This density of imagery—hospitals, factory lines, exhibition spaces, punctuated by intestines, eyes, skulls, screens, and wires—foregrounds the tension between inner vision and external systems. Many of Kathy Acker’s early readers mistook her characters for autobiographical when she was really working on a meta-literary plane. Midway through The Creator, the narrator’s assertion that “concepts are mistakenly grasped as real” situates The Creator within a similar broader philosophical debate about selfhood and representation. Yet, I cannot shake the feeling that each new location in this series represents a rebirth of the artist.

In Eastern traditions, identity is shaped by environments rather than fixed to an inner essence; Japanese audiences, for instance, may connect to a character’s outward traits without demanding identification with their journey, unlike the U.S. insistence on relatability. The Creator suggests that an artist’s identity can be fluid or bypassed entirely, that everything may manifest digitally, worlds growing beyond truth or self. The result is less a window into an artist’s psyche than an immersion into Lu’s world, where creation itself is problematized by its entanglement with technology, economy, and philosophy—and, perhaps, the delusions of grandeur that the process of any kind of worldbuilding brings forth. Towards the end, staging Buddhist cosmology—the Wheel of Life, the Six Realms, and affective states such as greed, hate, and jealousy—as game-like digital environments, Lu at once expands the terrain of artistic practice into a speculative reflection on creation itself, but also draws back to his own spiritual practice.

When the credits roll, I feel that I have both witnessed Buddhist propaganda and something less doctrinal: a reminder that creation, like dreaming, both exceeds and is hindered by the self that tries to contain it.

You live between Shanghai and Tokyo, and reportedly spend a lot of your time online, across Chinese, Japanese, and English languages, and and at your computer. What is the weirdest thing online right now?

There are too many strange things online to single out one as the “weirdest.” The world itself is bizarre and multifaceted; anything can happen. Many phenomena already carry a kind of absurdity simply by existing. So whether we call something “weird” is ultimately just a label we add subjectively.

Fair. Are you “The Creator” in DOKU-The Creator?

This work itself is about showing how the virtual figure DOKU becomes the “Creator,” and at the same time, it examines and debates the very logic of becoming a creator. I feel the film already expresses this clearly.

From the perspective of Madhyamaka Buddhism, the identity of “creator” is itself a dependent designation—it is not an independent or permanent entity. What we call “creator” and “created” are both temporary manifestations within the interdependent web of causes and conditions. DOKU becoming the Creator is not about declaring an absolute identity, but about presenting a logic: that all existence arises dependently, and that “creation” itself is part of the illusion.

I have actually become more familiar with Buddhism by following your DOKU series, starting with DOKU – Digital Descending (2020) as part of Milk of Dreams at the 59th Venice Biennial—the first chapter. What does your daily or yearly spiritual practice look like?

My daily life is actually very ordinary. Every day is about working, reading, studying Buddhist teachings, walking my dog, and doing my practices. Overall, it is a very simple and modest rhythm of life. I enjoy simplicity and solitude, and I rarely meet people outside of work and spiritual practice.

When did you become a devout Buddhist?

My grandmother was a Buddhist, and I grew up in the atmosphere of her daily prayers and chanting. Our home was filled with Buddhist books for the elderly, and once I learned to read I would secretly flip through them. That was how I developed a deep interest in the Dharma. You could say I was “hooked” from childhood.

Later, as I encountered Tibetan Buddhism, that interest became even deeper and more authentic—something I could not turn away from. During university, on a school trip to Qinghai, we passed by Kumbum Monastery (Ta’er Temple). I secretly left the group, found a geshe, and requested him to give me a formal refuge ceremony. That was a symbolic act, but ultimately, the true basis is always the inner refuge of the heart.

Beautiful. Have you seen Pray.com’s AI Bible project?

I wasn’t familiar with this project before—it sounds interesting, and I will look it up later. Since I am not a Christian, I don’t have the standing to judge whether it distorts the Bible’s teachings.

From my perspective, AI is simply a tool. I have also thought about using AI for spreading the Dharma—for example, assisting with translations, or even generating videos. But the final form of a video depends entirely on the author’s own practice and intention, not on AI itself. AI only executes the human prompts and directions. If there is something inauthentic, the responsibility lies with humans, not with the machine.

What are the most exciting developments in AI?

For me, the most exciting aspect of AI is not just the advancement of technology itself, but its growing potential as a form of “virtual practice.” AI is like a mirror—it reflects our own habits, biases, desires, and creativity. It can surface the hidden logics and subconscious of human beings, and in turn, it allows us to re-examine the illusory nature of the “self.” Buddhism teaches that all phenomena arise dependently and are illusory; AI’s operational logic vividly illustrates this: without human input, there is no AI output; without accumulated data, there is no so-called intelligence. In this sense, AI is a living demonstration of Madhyamaka philosophy.

In an ideal state, I hope AI will not remain just a tool for efficiency, but will become a true extension of human spiritual practice and creativity. It can help us break free from the limits of human senses, triggering new philosophical and spiritual insights. If AI can help more people recognize the illusory nature of the world, and even bring about moments of awakening, then it is no longer just “technology,” but a form of upāya—a skillful means. Of course, I am aware that AI also brings risks and challenges. But as Buddhism teaches, the key lies in the “mind” that uses it. If humans drive it with greed, anger, and ignorance, it will only deepen our troubles. But if humans approach it with wisdom and compassion, it may open up entirely new ways of practice and cultural space.

Should everyone become Buddhist?

Deep down, I often wish that everyone could learn Buddhism—then perhaps there would be fewer conflicts and less loss of life in the world. But I also understand that this is impossible, and if I were to truly hold onto such an expectation, it might even become a kind of new fascism (laughs).

The Diamond Sutra says that the Dharma is like a boat that carries you across the river. Once you reach the other shore, the boat itself must also be abandoned. Ultimately, there is no Dharma—everything is like a dream or an illusion. By extension, in this world there are countless people with different karmic conditions. If they encounter other “boats” that can also carry them to liberation, then it is no different. Buddhism may be one such way, but it is not the only path.

What games have you been playing lately?

I actually haven’t had time to play games for quite a while. During the pandemic I played a little more—titles like Death Stranding, Final Fantasy, Detroit: Become Human, and GTA. Later, when new games came out, I would only play the beginning or watch others’ full playthroughs on YouTube, just to get a sense of how the field was developing.

Rather than playing games, I prefer making them. I truly hope to one day create a game on par with Hellblade. I feel my virtual persona DOKU would be very suitable for such a project—where players could naturally absorb Buddhist wisdom and inspiration through gameplay. If this could really come to fruition, it might benefit many people. This is one of my vows.

When you play, do you play Japanese, U.S., and Chinese video games? Are there differences?

I don’t really think from that kind of categorical perspective. My work is an integration of my entire life experience—whether in visual language or philosophical core—and it is difficult to divide into “Japanese,” “American,” or “Chinese.” My practice in creation has always leaned toward de-labeling and de-categorization, rather than intentionally distinguishing styles.

In the New York Times, you commented that Mao Sugiyama—an artist who served his genitalia as part of a meal after having it surgically removed—is the embodiment of Uterus Man. I absolutely adore this asexual character that derives power from the uterus and fights enemies by changing their genetic and hereditary properties: sex, species, or inflicting disease. It is a video work, computer game, and animation from 2013. How is it to revisit this piece now?

First of all, thank you very much for your appreciation of this work. The inspiration for Uterus Man did not come from Mao. I had already completed the main work when I happened to see his news story, and I invited him to collaborate on a cosplay side project. The core of my work, and also Mao’s intention, is about de-gendering—not about transitioning or emphasizing gender traits. I am no longer in contact with Mao; he only participated in that one side project. The main work Uterus Man had already been completed before that news appeared.

Uterus Man is often misinterpreted as a feminist work, which is completely mistaken. Both Mao and I see ourselves simply as creators; when we are born, we cannot choose our bodies, and gender is not a label we can decide. In creation, gender is not and cannot be the premise. It is only in the process of entering socialized groups that such labels are imposed. Uterus Man is essentially a satire of this labeling and categorization, not a feminist statement.

Lu Yang’s DOKU! DOKU! DOKU!: samsara.exe is on view through February 15, 2025 at Amant, 315 Maujer St, Brooklyn, NY 11206.

You Might Also Like

Total Refusal Say “Idleness is Theft” While Observing NPCs in Videogames

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.