Maya Yameng Li Shows it is Difficult to Remain Outside Algorithmic Systems, But Not Impossible

The premise of URBAN SURVIVORS? multimedia artist Maya Yameng Li’s solo show at Nguyen Wahed’s New York outpost is clear: contemporary cities increasingly operate through algorithmic systems that promise efficiency, clarity, and predictability. In that process, certain bodies and behaviors—stray animals, elderly bodies, slow or irregular movement—fall through the cracks and disappear. Presenting the artist’s observation, the exhibition frames these structural oversights as an intentional blind spot produced by optimization itself.

Much of the work relies on visual instability: fragmented animal silhouettes, blurred figures, looping movement, degraded images. These visual choices are intentional. Glitch, as a strategy, has long been absorbed into the aesthetic vocabulary of new media art. From Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism to Hito Steyerl’s essays on poor images and disappearance, glitches are signals for the resistance behind the structural forces. The motif is no longer surprising or disrupting but recognizable. Glitch as a style reads as a familiar language. What matters has become what Li asks it to reveal about her observed world.

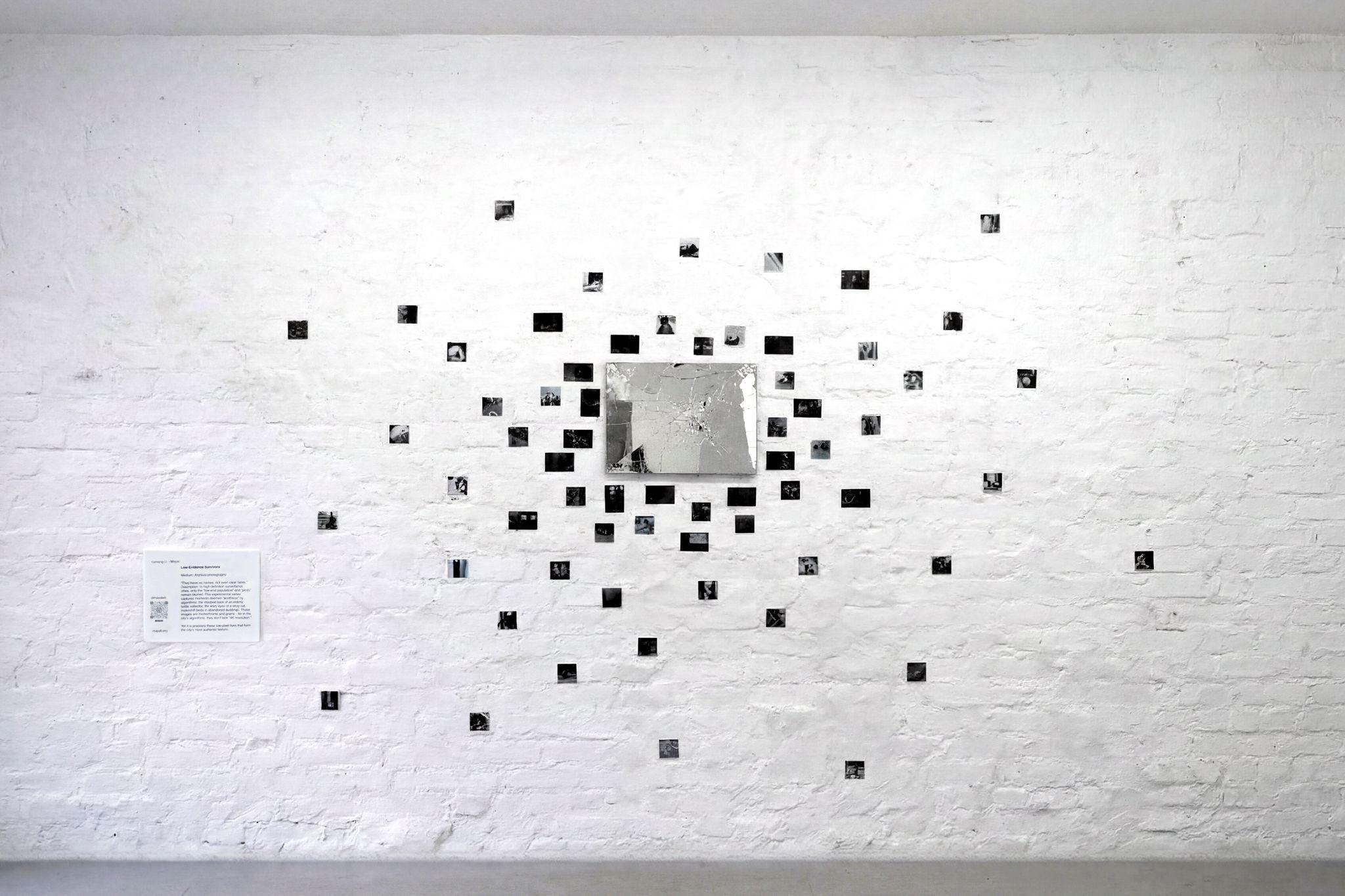

The show starts with a fieldwork-based exploration, Vector Latency: The Algorithm’s Eye. Surrounding a broken glass as a symbol for the fractured system are the field photography on the invisible points that Li collected. These pieces are dispersed like particles and pixels, evoking how information appears once it has been filtered and compressed. Looking through the piece, what emerges is a spatialized record of absence, with the observer’s face being fragmented in the middle.

The central installation is a dual-panel video, CAT TITLE and BIRD TITLE. The piece is a projection of animal forms onto translucent fabric, both literally and figuratively. The two animals depicted, a pigeon and a cat, flicker, fragment, and collapse on a light projection on two soft drapes. The translucency of the material introduces physical interferences into the projection, producing a ghostly image that is unstable even before any digital manipulation occurs. As Li explains, the animal images are not captures of living beings but her observation and impression of how they appear when projected into stable computational volumes. This translation produces a state of partial presence: visible, yet never fully held, mirroring how these animals exist within urban infrastructures that register them inconsistently, if at all.

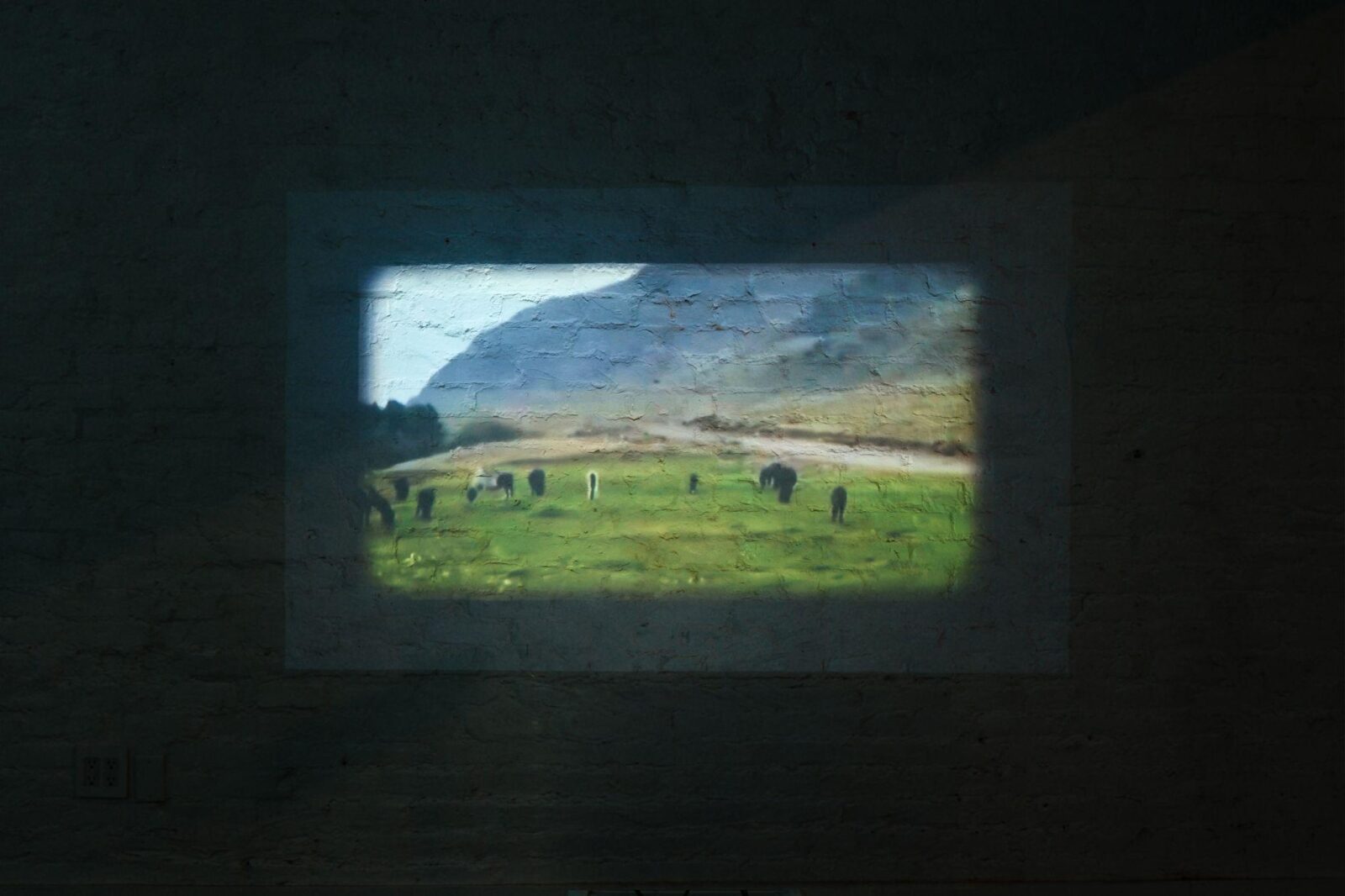

The loop video work named Margins of the City: A Loop Study, intentionally small and grainy, further leans on what Steyerl once described as the “poor image.” In the cut loop projected on a white brick wall, livestock live on organic landscapes that the artist describes as “void.” The gesture of graininess and irregular cut feels less like a polemic and more like an acknowledgment of an existence. Weirdly, in the unpredictable rhythm, the images are assembled and offer a sense of closeness and intimacy. The grass and the animals remain difficult to read, but the elements of nature’s realness resist any digitized fantasy. Solely the visibility alone produces understanding and resolution to some of the unsettling chaos that Li has expertly shown in the exhibition. She is uninterested in offering alternatives. There is no suggestion that better algorithms, better sensors, or even better representation would resolve these blind spots. Instead, the exhibition lingers on the persistence of lives that do not conform to systems built around optimization.

Looking at Li’s personal practice, I found that her website contains motion graphics with all the lighting and movements meticulously planned and optimized—reflecting her high degree of mastery in motion graphic design. Hidden in the corner of the site, there is a FUN tab that has alternative computational animation and sketches that are light-toned, romantic, and extremely lovable. It is at this point, beyond the exhibition and in Li’s peripheral space, that I begin thinking about daily practice. Not as a romantic ideal, and not as a heroic counter-gesture, but as a different temporal orientation altogether. Daily practices—drawing every day, making one thing repeatedly, returning without promise of improvement—do not oppose optimization head-on. They simply operate alongside it, often ignored by it.

Daily practice is not innovative. It is repetitive and often inefficient. Its value does not lie in disruption but in duration without obvious progress. Unlike algorithmic systems, which measure repetition as training data toward refinement. It allows inconsistency to remain unresolved. It accumulates without becoming optimized. What is often the result of such practice is human traces that are compelling and romantic.

This form of repetition has surfaced repeatedly in recent exhibitions and gatherings (in the past months): Nguyen Wahed in London showed a decade of Zach Lieberman’s daily sketches; SRC in DUMBO, New York City, hosted a celebration of Suraj Barthy’s ten-year daily practice. That these new media artists began their daily practices around the same period may appear coincidental, but yet the alignment suggests a shared response to the moment when digital production became increasingly governed by the gears of algorithmic optimization. Similarly, while Li is capable of fitting into the algorithm and producing optimized and high-quality visuals, glitch and daily practice become her choice of armor and weapon in the silent resistance.

Yet even this orientation is not immune to the power of algorithms. When glitch and slow daily practices are archived, shared, and ultimately fed back into the same system that rewards consistency, visibility, and accumulation, what begins as repetition without promise can quietly become data. In this process, such works risk reinforcing the comforting but false fiction that algorithmic systems are all-knowing and all-inclusive, further sustaining the illusion that nothing remains invisible under the banner of progress, even as new forms of exclusion continue to be produced.

Maybe, read this way, URBAN SURVIVORS? does not offer refuge from algorithmic optimization. It merely acts as observation and showcases how difficult it has become to remain outside the algorithm system. If the exhibition leaves any opening at all, it may lie in this recurring pattern: that once a mode of working is absorbed and contained, another form of friction eventually emerges—elsewhere, temporarily unreadable, and not yet optimized. And maybe, after all these rounds of recursion, creatives and artists will always find another way after the current resistance has been contained and absorbed.

You Might Also Like

Analog Surfaces Embrace Digital Realities at Zepster Gallery

Joiri Minaya and Nando Alvarez-Perez’s Sublime and Mysterious Grid

What's Your Reaction?

shuang cai is a curator, writer, and multimedia artist. Their writing and curatorial works aim to bring forth the power of interconnectedness and diverse voices across communities. Their art practices focus on logic, interactions, and humor. They hold a Bachelor's degree from Bard College, majoring in Computer Science joint Studio Art, and a Master's from New York University Interactive Telecommunication Program(ITP). Currently, they are getting their PhD in Human Computer Interaction at Cornell University and actively curating in New York City. They were an ITP research resident, the curatorial fellow at NARS.