When Cultures Clash, New Worlds Take Shape: Mi Ju

A Conversation with Korean-born artist Mi Ju.

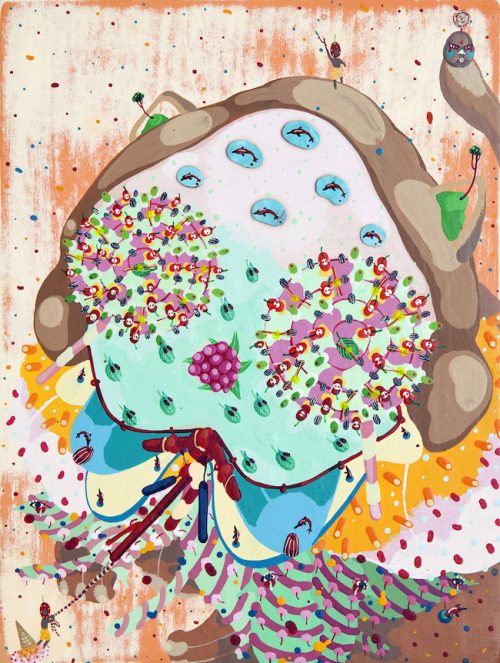

I first met Mi Ju, a South Korean-born painter, three years ago at an Open Studios event. I was awestruck by the world she depicted in her intricate paintings. Not only did she visually meld subject matters like flora and fauna with animal and insect-life, religious symbolism, and the supernatural in her paintings, but her work was, and still is, also a juxtaposition of Eastern and Western cultural elements. In lieu of seeing her solo-show in Denmark, she invited me to her Long Island City studio to preview and talk about the work; we discussed assimilation, migration, the craft of painting, nostalgia felt for our home countries, and how she deals with being a young artist on the rise.

As Mi Ju walks me up to her studio in a studio-complex, she tells me that she is amongst the youngest artists there. Long Island City is an area popular for the arts – MoMA Ps1 and SculptureCenter are just around the corner. With representation by two major galleries – Freight and Volume in Chelsea, and Gallery Poulsen in Copenhagen – it is only fitting that Mi Ju works out of an established neighborhood. The studio is neat. It’s furnished with a couple of tables, chairs, and a bookshelf stacked with books on science, art history, and, to my surprise, children’s books. It is funny how the objects artists collect in their studios migrate into their work. As I flip through Where’s Waldo and the stylized puzzle books that follow the same color scheme as her paintings, she tells me that she does not paint from shapes but from colors. Taking a cue from psychosomatic medicine, I would say that she paints from an emotional place rather than cerebral.

Mi Ju arrived at Pratt as a figurative painter who had already found her mode of expression. She felt like an outsider in the program that emphasized the conceptual and encouraged students to work across mediums. Her eyes shine bright as she flexes her hands and says with conviction: “I will paint until my fingers don’t work.” It can take up to four months for her to finish one painting, and she often works ten hours a day. Her regimented, self-disciplined working style is a product of her experiences in the Korean school-system as both a student and a teacher. She had a short stint working as a high school art teacher, teaching fifteen classes a day. Thus, her artistry strongly debunks the myth of chaos birthing creativity and passionate expression. The career of an artist, like that of a scholar, is often isolated. During the Ming Dynasty, Chinese scholars gained prominence in society not only as specialists in the classical rites, but also as philosophers, playwrights, and poets. Like theirs, Mi Ju’s work delivers insightful societal analysis.

Yellow Cocoon – her solo-show in Copenhagen – deals with beginnings and biological introspection. Mi Ju’s parents have clearly influenced her mode of expression. Her advanced interpretations of nature stem from frequent exposure to the floral world – her mother is a florist. And, her father runs a textile company; the flat quality of her paintings can be compared to printed textiles. Another source of inspiration is Gaia Theory, which suggests that organisms co-evolve with their surroundings. Perhaps Mi Ju’s attraction to Gaia Theory is a tool for her to understand and create a sense of warmth and belonging in America. “Friday Feast,” a rectangular acrylic work on canvas with thread and cut paper, and measuring more than a square meter, is a family portrait – two wide-eyed parents protect a child who looks up at them admiringly. Red lacquer bowls, brimming with food, float on the canvas’s lower registry. A multitude of small figures adorn the piece. Although the title promises a feast, I detect melancholy in the child-like figure; the flower stem on the right is reminiscent of a tear. Mi Ju tells me that she misses her family, which is clear in her work. In “Family Portrait,” on view at PULSE Miami, a family of five are depicted, four stacked on top of each other whilst the fifth is disconnected. I wonder if these vibrant paintings are a precursor to future projects in Korea. We discuss the potential of collaborating with her father to design textiles from afar.

Mi Ju’s perception of art is as something fluid. She is fond of the African-American fabric sculptor Nick Cave whose popular sound suits bear resemblance to African ceremonial attire. He once complimented her on her outfit, she tells me modestly. She does not value one art form over another – a sentiment more common in Eastern than Western art-making traditions. An approach that lends itself well to the design work that Mi Ju is interested in approaching is textile or toy design, maybe in collaboration with her father. Judging by the expertise in which she carries out her visions in paint, seeing them in 3D will be mind-blowing.

The American painter Peter Saul – who delivers succinct political satire in bulbous, gruesome cartoons – inspires her. Both artists produce snapshots of cultural phenomena. Mi Ju has experimented with a new format of smaller paintings, beneficial for collectors with thinner wallets. The composition of “Shoo-gah” resembles Chinese Shan-Shui – paintings that are vehicles for philosophy, often depicting mountains and water. Both Mi Ju’s Eastern past and her Western present dictate the iconography of the compelling image. It portrays a lone Native American, victoriously reaching towards the sky atop a mountain that has dolphins for brain cells, grasping what looks like a hand puppet. The German Art Historian, Hans Belting, advocates Global Art: an art that is contemporary, a counter movement of regionalism, and void of the universal context that is prevalent in modernism. The key to deciphering Mi Ju’s work is approaching it from a multicultural perspective.

We spend a fair amount of time speaking about the refugee crisis that has hit Europe like a slap in the face. Opinions differ among legislators, the public, and nations; some countries, like Sweden – my home country, and Germany are pulling more weight than others. Now, security measures have been implemented on the boarder between Copenhagen and Southern Sweden to deter refugees. This has resulted in severely decreased mobility for the many that live in one country, but work in the other. Sadly, rising Islamophobia, rather than more productive discussions on how to transform refugees into a functioning work force, draws media attention. We both believe that the world must aid the millions of Syrians currently displaced.

Whether or not the visitors of Mi Ju’s exhibition in Copenhagen perceived the issue of migration featured in her work, it is there to be absorbed: consciously or sub-consciously. Mi Ju’s works are, in this context, a societal intervention – utopian visions – proof that when cultures clash, new worlds take shape.

This article was commissioned for Artterritory.

The exhibition Yellow Cocoon was on view at Gallery Poulsen in Copenhagen, Denmark, between 15.01 and 22.02.2016. For more information about the works on view, see their website,www.gallerypoulsen.com.

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.