Nikita Seleznev’s “Shaving of the Christ”

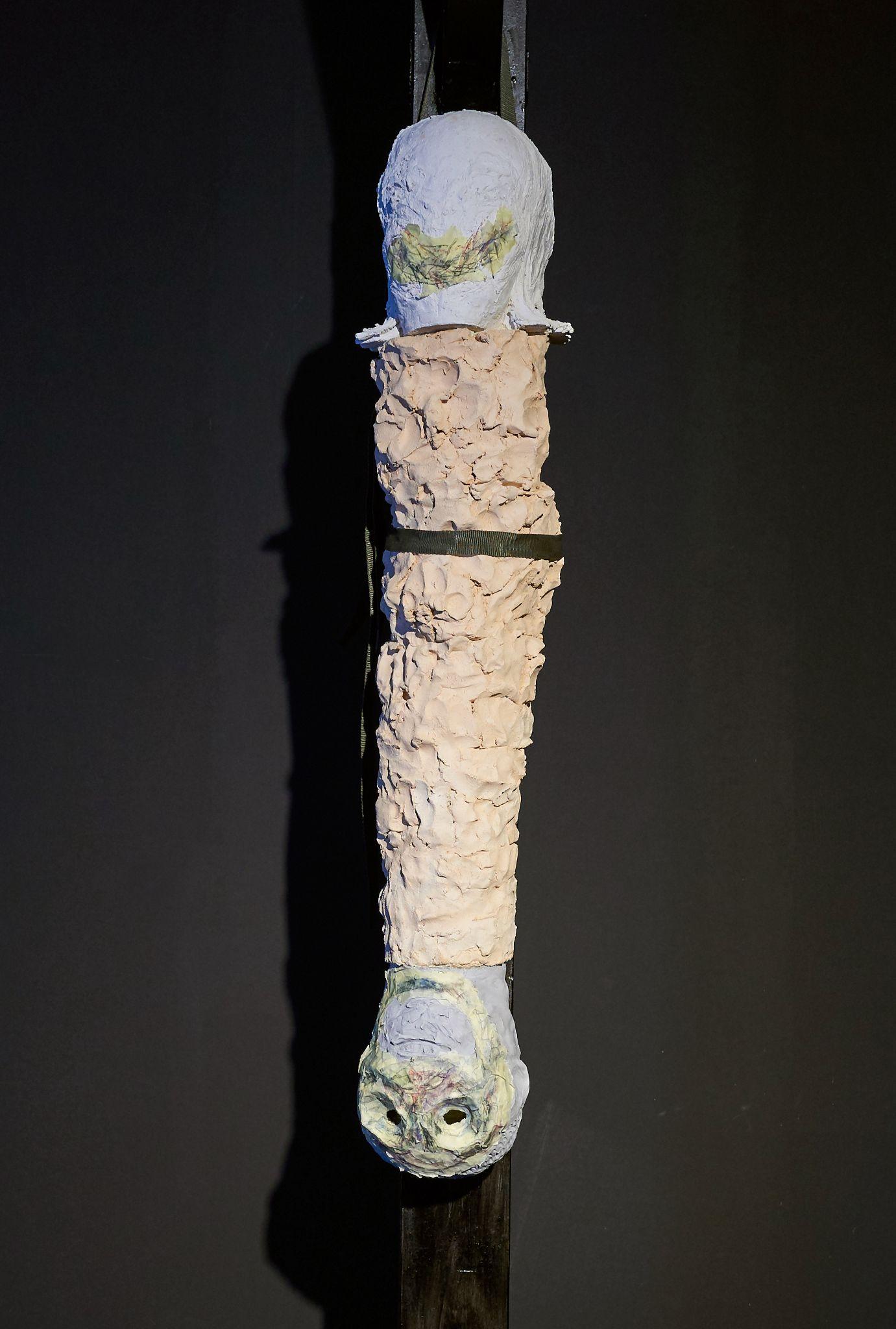

Within the Catholic Church, there is a strong and established culture of relics—mostly hair and bones of saints—these were rampantly traded as commodities, especially during the medieval period. French King Louis IX built Sainte-Chapelle to house Christ’s crown of thorns, a very precious relic. It was suitable for the monarch who enforced Christian orthodoxy and reigned during a prosperous era. Enter the Victorian era and hair relics are not only reserved for saints, anyone’s hair can be made into a relic for a loved one. Relics connect the living with the dead. The physicality of Christ is pervasive in Christian doctrine, parishioners believe that they eat and drink the body of Christ with the eucharist sacrament, and Christians of various denominations speak about the spirit of Christ and God physically present in their own bodies. Selezny’s work Shaving of the Christ (2022) evokes this preciousness of hair with an obvious nod to death. It is a series of sculptures and a video in which Christ’s head is shaved. Recalling the scene where new recruits to the military are shaved in the film Full Metal Jacket (1987), Seleznev juxtaposes the materiality of Christ with militarization of humans. In the military, personnel must sacrifice for their country, like Christ did for his people. Perhaps because of a global rise in conservative politics and a bi-prouct of indigenous and spiritual thematics, the art world has seen an increase in Christian themes. Seleznev depiction of Jesus, one of history’s most reproduced images, is not one of idolatry but rather critique.

Hailing from Perm, a major city in Russia’s Ural region, Seleznev temporarily lives in Georgia, in exile, after having left Russia since the most recent invasion of Ukraine and the escalation of the war. Shaving of the Christ marks the first body of Seleznev created out of Russia. According to the new testament, Christ is the savior of the world. Soldiers of the Russian Army are recruited to “save” Russia, and fight the war. A well-recognized artist, Seleznev, like many others, did not want to take part instead, he wants to continue focusing on making art. Bringing a mirror up to society his works are throught-provoking. Seleznev’s work is collected by The Museum of Russian Art in Minneapolis and has been shown at Moscow Museum of Art, 6th Ural Industrial Biennial, and Garage Museum of Art.

The only King to be canonized, Saint Louis used the church to strengthen further and show his power by waging wars and prosecuting other religions. Similarly, Russia’s current president Vladimir Putin has used the Russian Orthodox church to back his efforts to overtake Ukraine. In addition to his support from the Russian Church’s Patriarch Kirrill, Putin has recalled the twentieth-century Russian saint Chernihiv, a monk, who said that Russian, Belarus, and Ukraine were the Holy Rus’ that could not be separated. There are many precedents where Christian imagery and iconography and church backing have been used to impress on people. Seleznev cleverly uses the image of Christ to critique this blind faith to leadership.

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand: Is there an afterlife?

Nikita Seleznev: I think not

AME: What is your personal relationship to Christ and Christianity?

NS: I am not a religious person. Christianity for me is connected with sensual experience that is absent in everyday life. As Bataille writes: Religion tries to resolve the internal conflict between the anxiety associated with mortality and sexual desire and the world of organized work. I often refer to this conflict and look for the role that art plays in it.

Living in St. Petersburg, I observed the growth of right-wing politics and how the Russian Orthodox Church became one of the instruments of propaganda. Orthodoxy is one of the most taboo topics in Russia. The two-year imprisonment of the Pussy Riot art group’s leaders in 2012 for holding a performance in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow was a demonstrative revenge on the top of the Orthodox Church. And public tolerance untied the hands of state violence even more.

For me, working with the image of Christ is also a personal challenge. Testing inner freedom. A test for which you need to step aside and begin to consider Christ as if you were seeing him for the first time.

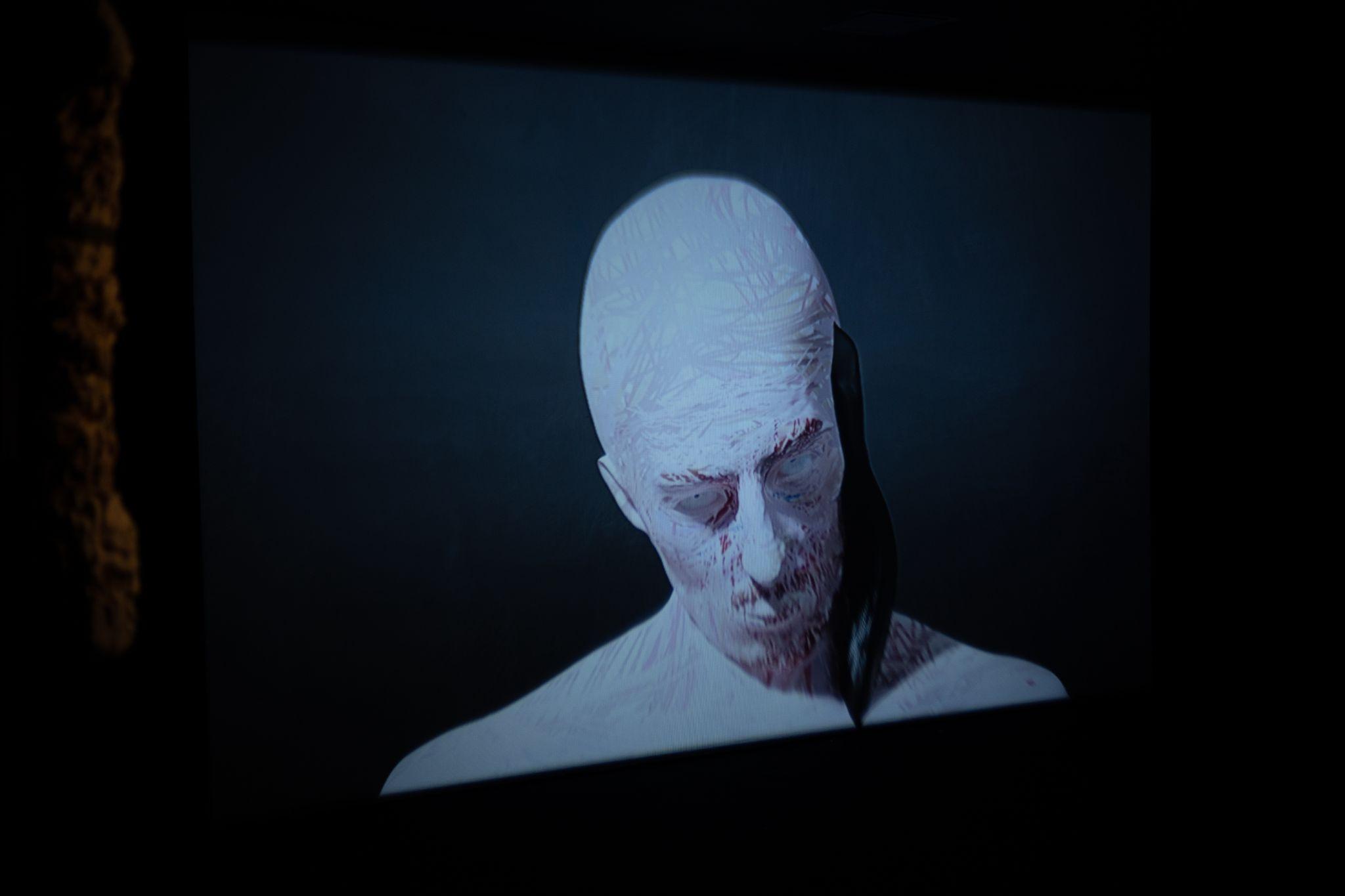

AME: Shaving of the Christ consists of a 3D animation as well as multiple sculptures—deconstructions of sorts—mainly in ceramic. What influenced your rendering(s) of Christ?

NS: For me the image of Christ is very human. My Christ is a guy made of skin and bones, as well as a lot of anxieties and worries. Ceramics emphasize this fragile physicality, while 3D projection, on the contrary, creates a distance. Christ is all sorted into quotes, and as you rightly noted, each part of his image is an artifact. When I was working on the project, I considered a huge number of images, but none of them became the basis for sculptures and animations. I was only interested in the intense attraction that these objects spread out.

During my education at the Stieglitz Art Academy in St. Petersburg, I studied white stone carving and participated in several expeditions to study and copy sculptures of the 12th-13th centuries. And before that, there was a collision with a Christian wooden sculpture in Perm, the city where I was born. I liked that the objects I saw were mysterious and complex. It was an experience of colliding with something fundamentally different. I wanted my work to give the viewer a similar experience.

AME: Now is a difficult time and this work is heavy, however, in the past you have made works anchored within humor. Why is humor important in art?

NS: Humor is an amazing thing. I think that often my art is riddled with irony, but I never try to make a joke out of my works. I am fascinated by some stories, and I want to talk about them. They can be funny, cause a smile and laughter – this is how humor becomes part of my work. In the Karte Poetry project, I showed amateur translations of popular songs on a huge screen, and around there were concrete sculptures based on pictures from Internet publics; many thought that this was an irony on modern pop culture, but this culture sincerely admires me.

AME: Actually, I’m sorry. Is this a difficult time for you? What are your feelings?

NS: Don’t be sorry. Until February 24, I could not believe that Russia would start a military invasion of Ukraine, and when it happened, like for many, it was a complete shock for me. Ukraine for me is not just some random country: my family members are from there; my grandmother was born there. In 1945, her family was forcibly transported to the north of the Urals. Our family has always said that it was luck because many residents of the occupied territories were shot during the post-war Stalinist repressions. Now I feel like it’s all happening again. Totalitarian politics, repression and cruelty are global problems, and we must fight them. Therefore, we must not lose heart: we still have much work to do.

AME: How is life in Tbilisi? And how do you think the cultural life and sphere in Russia will be affected by the mass exodus of artists and cultural workers?

NS: Moving to Georgia was a drastic but balanced decision. My anti-war position became criminalized in Russia, so my wife and I left in early March.

In September, after the mobilization announced by Putin, the second wave of emigration began. A lot of men left Russia. Friends came and stayed with us, and this was the case in the homes of everyone I know in Tbilisi. Many of my friends from different creative fields have moved: artists, curators, photographers, designers. People slept on yoga mats, in sleeping bags, and in general, where and how necessary. It is terrible when you are forced to leave your country, but there is great value in the way people help each other.

By starting the war, the Russian authorities cut off the possibility of dialogue with contemporary culture. Totalitarian politics is destructive to the development of art. You see how the world culture is developing, and your thoughts are occupied with the fact that a distraught dictator sends your brother to kill your friends.

AME: Shaving is also liberating. Remember the pandemic buzzcut trend, which I also got hooked on. I felt much lighter after I got rid of my locks.

NS: Shaving hair is indeed a very ambivalent act. The first thing I did when I left for Tbilisi was to shave my hair short under a typewriter. This had a liberating effect.

The hair of Christ is one of the most important parts of his iconography. When this hair disappears, instead of an icon, a defenseless body remains— he becomes more fragile and humanlike. It seems to me that Stanley Kubrick accurately recognized this in the first scene of Full Metal Jacket.

AME: As a sculptor, how is it working with 3D animation?

NS: I’ve been interested in expanding the sculptural media for a long time. I started by combining sculpture and sound. Gradually moved on to installations, which include 3D animation. Animation gives me the opportunity to work with the display of time in sculpture. The combination of “tempered” sculpture with classical sculpture creates a new space for the development of artistic language. This brings my practice closer to how modern cinema uses the heritage of surrealism, creating a space of fantasy or dream inside the film. For example, as in Michel Gondry’s The Science of Sleep.

AME: What is a piece of advice that you have taken to heart recently?

NS: Keep making art. Terrible events, such as the war unleashed by your state, make you feel like a loser. Efforts seem in vain when a person’s life is devalued. Despite this, you need to keep working. Art is a complex social construction that does not give instant results, but it can influence changes in society.

Nikita Seleznev created Shaving of the Christ (2022) while he was at the residency Ria Keburia in Tblisi, Georgia and it is currently on view in their galleries.

You Might Also Like

An Intimate Sense of Dislocation: Warsza’s Roma Pavilion in Venice and an Itinerant Friend

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.