Rachel Rossin’s Virtual World: How the Invisible Infrastructure of Technology Helps to Parse Reality

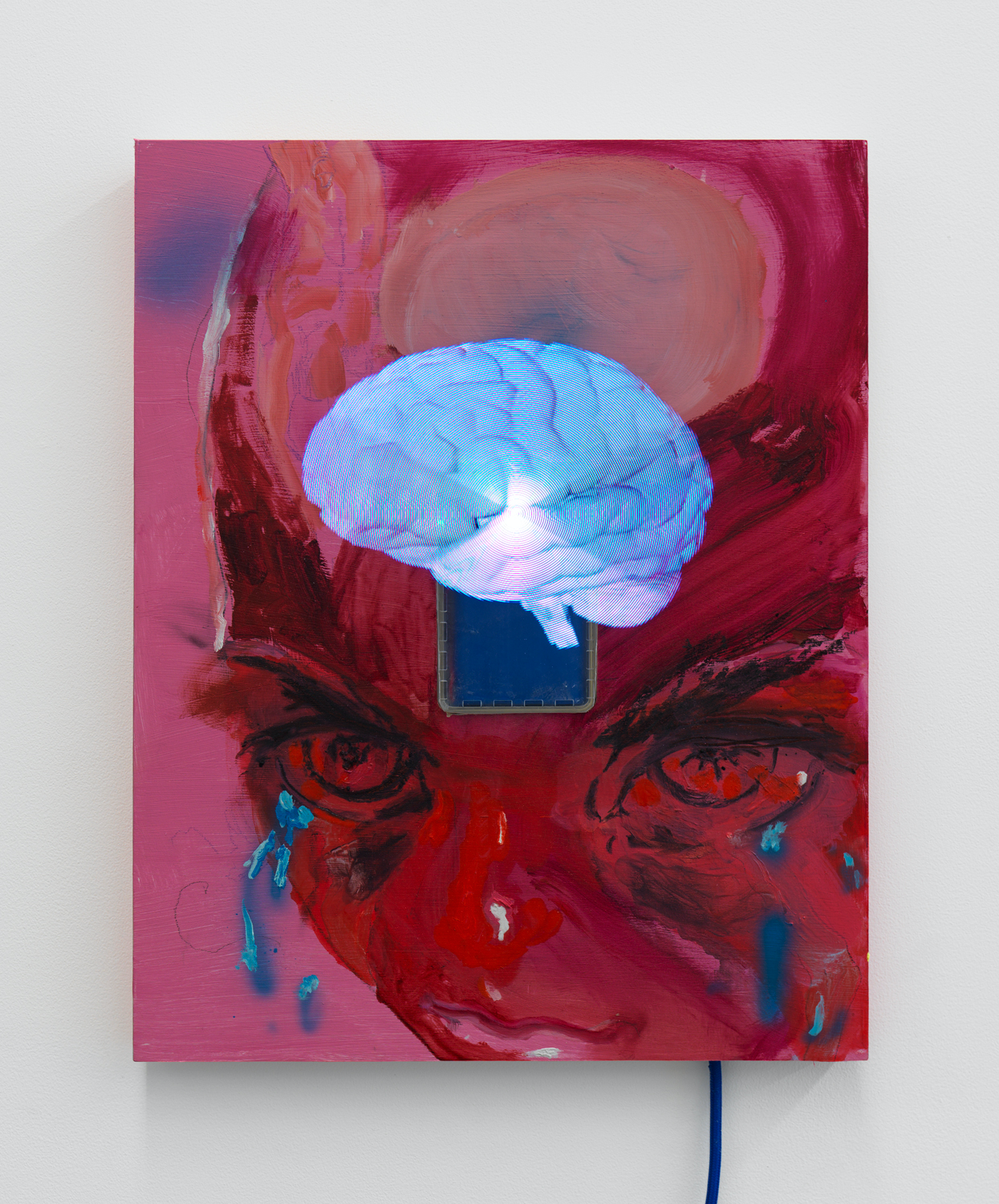

Rachel Rossin is a New York-based multimedia artist, virtual reality savant, and self-taught programmer whose works blend the boundaries between the physical and the digital. In her current solo show at Magenta Plains, Rossin presents a body of new gestural paintings that are at once captivating, yet disorienting, subtly weaving together digital and traditional art-making methods. Titled “Boohoo Stamina,” the exhibition addresses themes of loss and healing, and explores how the invisible infrastructures of technology and the internet have come to define how we’ve experienced life–the good and the bad–over the last year.

Speaking with Cultbytes, Rossin gave us a close look into her practice, including how she first became involved with virtual reality, the ways in which technology can be both therapeutic and escapist, and her view on the current makeup of the NFT market.

Annabel Keenan: Your current exhibition at Magenta Plains is a great showcase of your work, as well as a more personal look into loss and self-repair. Before diving into the show, can you explain how you became involved with VR and programming?

Rachel Rossin: It really started with my great grandfather, who was a mechanic for Burroughs Adding Machine and then IBM and was a really intuitive person when it came to hardware and technology. He left a lot of these old machines when he passed. They were really just old parts and, as a child, I got into putting them together and breaking them apart, which built my understanding of computing and hardware.

AK: How did the art side of things evolve?

RR: It evolved more specifically out of the only machine that he left that actually functioned – a dot matrix printer that was command line, which is just text on the screen without a virtual space. Those are my first memories of how art became involved by making these drawings with the dot matrix printer. I have an Art21 documentary that came out on May 5th and I talk about this a lot because my mom actually found these first drawings that I made – and the date on them would mean I was six. It’s crazy to think that I was using command line at age six, but I was just doing what children do – playing and accidentally breaking things.

It gave me the advantage in terms of access to understanding early computers and programming. When Windows 95 came out, which was the first graphic user interface for an operating system that I was introduced to, I knew exactly what was behind there and I was able to then see code as something completely familiar. It felt very native and very much like home to me.

AK: What made you want to actually create virtual art and virtual spaces? Understanding the technology is one thing, but your dedication to the craft has spanned nearly 30 years.

RR: For me it has to do with escapism, which in a lot of ways can be a form of therapy. I think this is the same for other people as well. Of course, this can also be very unhealthy, but it can also be a necessary way to parse reality or to cope with reality where you need a break. I grew up in South Florida in a pretty frenetic environment with a lot of siblings and my parents were stretched thin financially, which led to pretty consistent uncertainty. This really contributed to my wanting to make art as virtual spaces that were proxies for home.

AK: This brings me to my next question about the works in “Boohoo Stamina.” This idea of loss, healing, and self-repair is evident in the exhibition title, and it really comes through in the works themselves with imagery, like the Caduceus, crutches, crying eyes, and the aluminum braces. There’s definitely a sense of the show as a kind of proxy and a venue through which you can heal. How did this show come to fruition?

RR: Thank you for that question and for really looking into the content of the works. It’s one of my more vulnerable shows. It might not seem like that on the surface, but when you really get into the material, you see the repeated imagery of the harpies, which is an avatar I frequently use, as well as the Caduceus, which I’ve been using for about a year. I like the Caduceus because it’s so ubiquitous and has persisted for as long as through human history, which makes me feel small. I love it as a symbol that has hung around and more or less stayed the same visually, but how did we get here? It’s so archaic and it’s been passed down across cultures and reached beyond language.

There’s this imagery related to loss and healing, and, as you mentioned, the title “Boohoo Stamina,” of course points to that as well. This past year has been difficult for everyone with all that we’ve been through, and I’ve lost five people that were very close to me. At our core, we’re all going through things and working on processing these bigger human feelings. It’s been interesting to see the role that technology has played. That’s the question that the show is posing: what is this invisible infrastructure that’s put this grid on top of all of us and how has it served us in times of tragedy when we’ve been so isolated? I’m interested in the way that I lean on technology now and the way that I leaned on it when I was younger. Now there’s this fatigue that really came over the last year, which is why I decided to make the larger paintings in the show, which are symbolically me leaning into the body and leaning into the language of painting using expressionistic marks – marks that really hold time. There’s something interesting to me in how expressionistic paintings hold time, you can see where the artist stood, how they held the brush, which contrasts heavily with the language of technology. There’s a sterility and stiffness to technology, even if there are time-based elements.

AK: This exploration of the digital and the physical spans across your practice. You often incorporate elements of your digital creations in your physical works, and in turn your digital art takes cues from the physical forms. Can you explain what’s involved with this process?

RR: It’s funny, I really can’t tell you how this happens. I can track some things when I look back on them, like the Caduceus started as drawings and they turned into a sculpture that I made in a VR application. A lot of the VR space that the paintings are based off of are spaces I make on reflections about embodiment, but they’re made when I can’t see my own body. There’s this real sense of deja vu of how the body feels. From there it can become a simple, playful, mindspace where things just come up. I use this VR space the same way that I use my sketchbook, but the difference is that in a virtual space, I’m able to move around more freely. I used to lucid dream frequently in high school and it’s very similar to that where you’re able to move the light around and control things and sketch in a way without this flatlander approach. In contrast, when I am making actual VR works I approach those as project-based. My virtual reality works are self-contained ideas. There’s not a lot of chance that can be blown into them. They’re executed in much more of a game-developer approach, which is pretty straightforward.

AK: A few of the works in “Boohoo Stamina” embody a close weaving of the digital and the physical with holograms embedded in the actual surface of the paintings. The exhibition is somewhat disorienting in that sense, where the visitor struggles to understand where the physical ends and the digital begins. When did you start experimenting with holograms in your work?

RR: Around 2018, but what’s really interesting is that it’s essentially an old technology, a zoetrope with LED. I spoke recently with Zachary Kaplan from Rhizome and Scott Fisher, who was at the forefront of inventing VR, and we were talking about his fascination with stereoscopic images and how a lot of these technologies have existed for so long, but you just wait until you need to use them. It’s almost like persistent amnesia. In a way technology is so frail, but it’s also very familiar and always around even if you’re not using it, much like the image of the Caduceus. There’s this sense that we need things to be novel for them to be relevant when they are just essentially tools that we already have. I like exploring that.

AK: The holograms contribute to the blurring of the physical and digital spaces of the gallery itself. They add an unexpected layer with the flickering images and constant whirling noise. Then, when you go downstairs, the whole lower level is cast in a blue light that completely transforms the viewer, as if they’re one of your avatars in your virtual world.

RR: Absolutely, I’m so glad you got that. I really wanted it to work. I was worried that putting the gels on the lights would cast blue on the paintings, so we had to be careful about finding the right type of spotlights that could cut through the blue to still properly light the works. That was a bit of a quest that I thought was really worth it, even though it’s so subtle. I wanted it to feel like you were a part of this virtual, foggy blue space.

The first time I went down to the lower floor of the gallery to see if the blue light would work, I felt instantly small, like I was in some sort of simulated environment. And I was like, yes, yes, yes, yes. This smallness, and even sadness, that comes through is associated with virtual spaces in general when you’re separated from people, which we all are now in real life. That’s really how I’m feeling right now, because of how much my social interactions and relationships have had to lean on virtual spaces. I felt that it’s necessary to express this, as well as our perseverance and stamina.

AK: In your previous works, you’ve explored the concept of the sentinel species, like the canary sent into the coal mine to detect danger before people enter. The avatars in your works at Magenta Plains take this idea even further. Can you talk about how “Boohoo Stamina” relates to your earlier explorations of this idea?

RR: Oh, I’d love to. “Boohoo Stamina” is sort of the sequel to a show that I had in September at 14A, my gallery in Hamburg, that was called “The Sentinel (tears, tears)”, where I actually trained a canary to sing dubstep. I had been learning about the finch family of birds and the way their neurology works from a whitepaper on birdsong and electronic music. Essentially, when they are learning a new song, usually when they are still young, there’s a pattern rhythm that makes them take to EDM and dubstep quickly, as the beats per minute is similar to birdsong. I’ve been training finches with electronic music for years. As we were leading up to the pandemic I kept hearing people talk about sentinel species and the canary in the coalmine, and I decided to make a video of me training the bird titled “The Sentinel” to accompany the show. The whole idea feels to me like two parts, the first with the canary project and then this second part with avatars as these sentinel beings.

My most recent NFT relates to this work and you can see the canary that I trained is scoring this larger virtual reality simulation, but the longer video of me training the bird is 20 minutes and really works better in a gallery setting.

AK: Speaking of NFTs, you’ve always been working with digital art and in this hybrid space of digital meets physical, but, for a lot of people, this is a new topic. As we’ve all seen, the NFT market has gone wild over the last few months with an increase in minting and buying from seasoned digital artists, young artists, as well as speculators. How do you feel about this increase in mainstream NFT popularity?

RR: I think technology is here to stay, but this is an interesting time. Unfortunately there are a lot of similarities to an MLM (multi level marketing) or Ponzi scheme kind of thing going on where you do see some younger artists that don’t have a market trying to enter the space and not do well. The people who are doing the best in NFTs already have big art markets or are famous or have some sort of footprint like a lot of followers. I think about my friend Rafaël Rozendaal, who has been making digital art for some 15 years and is doing extremely well with NFTs. For someone like Rafael who has been putting in the work over years and years as a completely dedicated artist and has finally been able to make money from this new popularity, that’s amazing and completely deserved. This is his medium and this is what he cares about. But then you have people without any established market coming in and spending like $300 on gas fees, depending on how Ethereum fluctuates, and they’re hoping that they’ll make that money back.

It reminds me of those art competitions in the backs of magazines where if you send in your drawing of the dog copied perfectly, they would give you some sort of elaborate prize. You’d have to pay five dollars or something and hope to win. A total Ponzi scheme. That’s the unfortunate part of people jumping into NFTs remind me of and that makes me worried for them.

AK: That’s a really good comparison. I have one final question, what’s coming up next for you?

RR: Next up I’m included in a show opening May 7th [World on a Wire] that is a commission from the New Museum and Rhizome in partnership with Hyundai. It’s a touring exhibition that began earlier this year as a kind of museum outcropping at Hyundai studios and I’m joining the one that opens in Seoul. I’m also very excited about the Art21 documentary that I mentioned, and I will have some new NFTs releasing soon which will be on my Foundation page.

“Boohoo Stamina” is on view at Magenta Plains, 94 Allen Street, through May 22.

You Might Also Like

What's Your Reaction?

Annabel Keenan is a New York-based writer focusing on contemporary art, market reporting, and sustainability. Her writing has been published in The Art Newspaper, Hyperallergic, and Artillery Magazine among others. She holds a B.A. in Art History and Italian from Emory University and an M.A. in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center.