Woven, Not Stranded: A Retrospective of The Web

Between a much anticipated opening in 1990 and its closing in 2013 The Web, 盘丝洞, pulsed with American Disco and House music that kept crowds dancing well into the night. Three years before Lucky Cheng’s served brunches and employed Asian and Asian-American Drag performers in the East Village, an Upper East side multi-level venue on Madison Avenue at the East 58th Street corner was the first Gay Asian-owned Gay bar in New York City, a distinction that, sadly, remains unchallenged to this day. People of color own very few LGBTQ nightlife businesses in New York City. Aside from The Web and Alibi opening in Harlem in 2016, Queens was the only borough where Queer people of color owned LGBTQ+ bars. Twenty three consecutive years in Manhattan for any LGBTQ+ club is a significant feat. Clubs with far less duration have influenced generations, pop culture, and became legendary: Mineshaft was only open from 1976-1985.

The Web remains part of New York City’s undercurrents of modern Queer lore, a constellation of citywide locations well known to those who were there but obscure within the scope of mainstream recognition. A current exhibition at the Chinese American Arts Council is the first retrospective of this unique home for Queer Asian communities. Titled The Web: The Birth and Legacy of New York’s First Asian Gay Bar, and co-curated by Xiaojing Zhu and Yukai Chen, the exhibition features photographs, ephemera, and an installation to celebrate the cultural touchstone The Web was for so many Asian and Asian American New Yorkers.

Created by Alan Chow with business partner Chan and borrowed funds, the club was named after a 1967 film, The Cave of the Silken Web, “an erotic film about spider women in a cave who tempt visitors,” Yukai Chen explained, “and the internet too, because it was at a time when it started appearing in daily life.” Chow and Chan transformed a fire-damaged private club into a space where Queer Asian communities could find refuge, belonging, and collective power as organizers of the first Asian contingent in New York City’s Pride Parade.

Mr. Chow, a Taipei-born actor who relocated to Hong Kong for a successful acting career, moved to New York City in 1971 and began promoting Chinese opera in addition to starting a small souvenir business. Mr Chow also had the starring role in The Cave of the Silken Web, among other Shaw Brothers Pictures in Hong Kong. As the founder of The Chinese American Arts Council, Mr. Chow maintains the photographic archive of The Web at CAAC and supports a growing roster of artists with an independent gallery.

What follows is an interview with co-curators Yukai Chen in New York, who works closely with Mr. Chow at the CAAC gallery, and Xiaojing Zhu in Beijing.

Patricia Silva: I’d like to start with Mr. Chow. Where did Mr. Chow live before starting The Web?

Yukai Chen: Mr. Chow was born in Taiwan. His family was from Shanghai and owned Ming Sing Florida Water, a famous cosmetic brand. When Mr. Chow moved to New York in 1971 he realized there was a need for a space where Gay Asian immigrants could hang out. Going to the existing Gay bars could be intimidating for those who didn’t speak English, so he co-founded The Web.

At first, Mr. Chow had two business partners but they didn’t like each other. The other partner David went downtown to lower Manhattan and opened his own bar, but it only survived for a short time. Mr. Chow eventually opened The Web with Chan.

What was on that opening night playlist? At this time, I was listening to Faye Wong covers of Western songs.

Yukai Chen: I love Faye Wong too, but The Web actually didn’t play many pop songs from East Asia. Mr. Chow said their playlist included American songs, mostly 1990’s Disco and House vibes.

On opening day it was packed. It caused quite a stir — people were lining up all the way down 54th Street. While Mr. Chow was promoting the club’s opening, people actually waited a long time, about two months, because funding and renovations weren’t ready yet. That long build-up made everyone even more excited, which is why so many people showed up when The Web finally opened.

Why did The Web close?

Yukai Chen: It closed in 2013 because of the rising rent and people not going to Gay bars anymore after dating apps appeared. Mr. Chow also said 9/11 was a turning point: people were afraid to go to crowded public spaces, but The Web still existed after 9/11 until 2013.

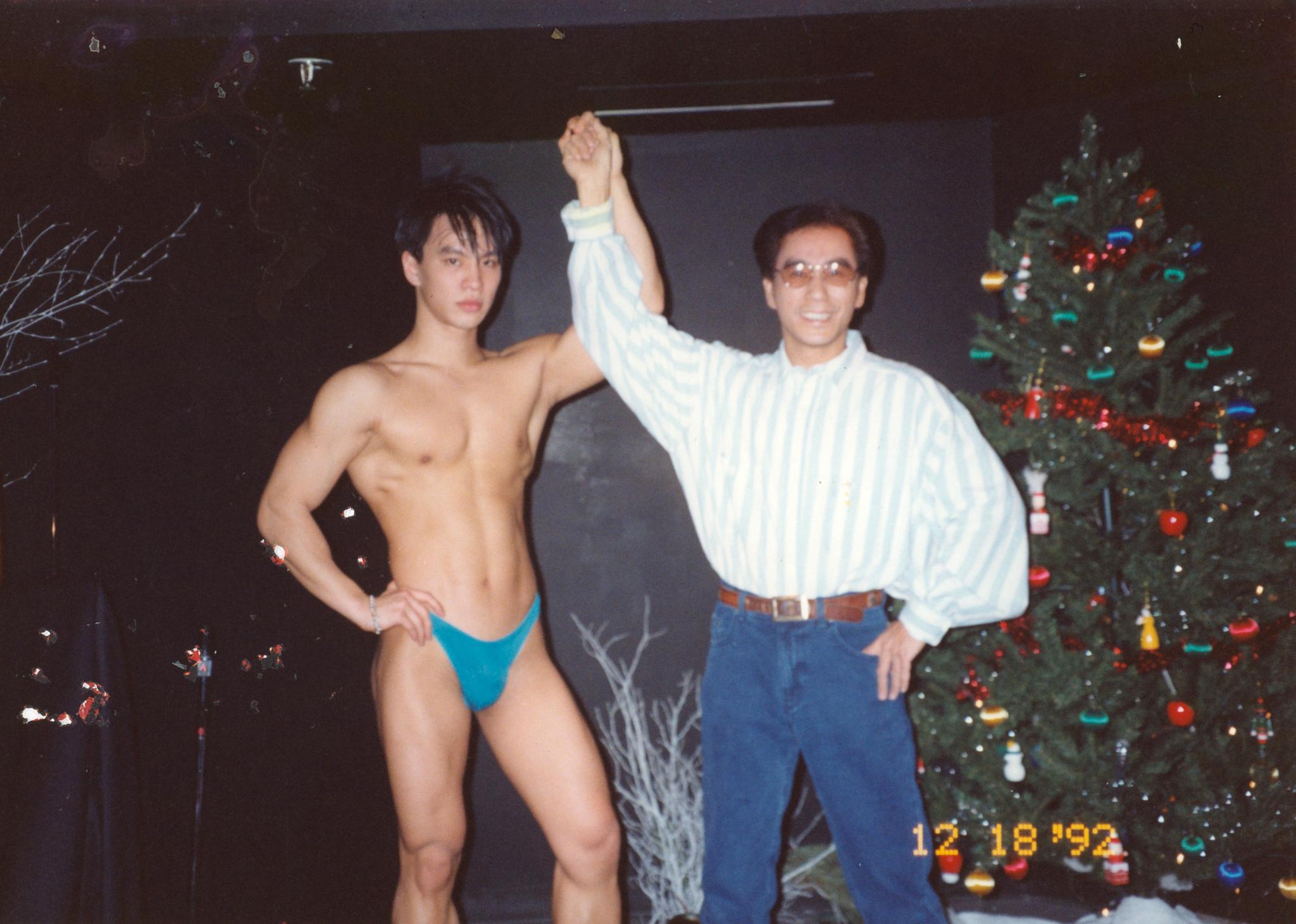

I would love to hear about the importance of Go-Go Boys at The Web. Every photograph in the show portrays a conventionally attractive Go-Go Boy, gym-chiseled, but in American media in the 1990s Asian masculinity was portrayed very differently, if at all.

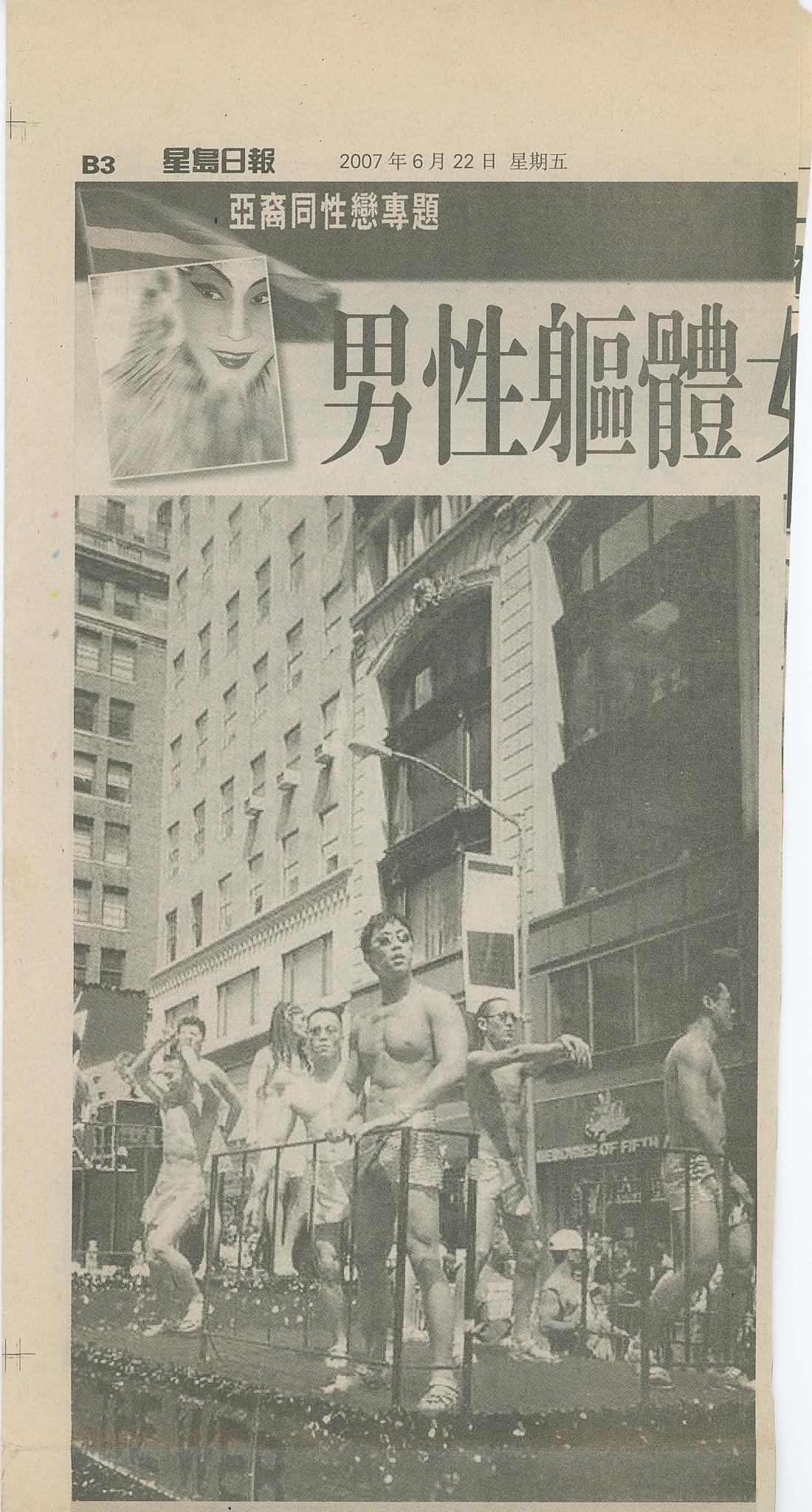

Yukai Chen: During my interview with the mural painter Chen Danqing, now a famous artist and critic in China, he mentioned that The Web successfully showcased the different aspects of Asian men. I mean, there’s Bruce Lee, of course, but seeing so many Asian men knowing they are sexy and unapologetically proud of it was rare for Americans. Chen Danqing said every time The Web’s float came out during the NYC Pride Parades, the audience would go crazy. That’s how The Web won The Most Outstanding Float four times. Chen Danqing vividly remembered that during one parade, there was a white man following The Web’s float, dancing and cheering with his headphones on. I believe The Web’s atmosphere was contagious.

Most of the Go-Go boys at The Web had day jobs. A customer of The Web came today and told me he knew a Go-Go boy who saved his one-dollar bill tips in a large plastic trash bag—and he used them to buy a laptop for school! The cashier was shocked and was unwilling to take these bills, but the Go-Go boy unapologetically insisted that money is money and eventually got the laptop. I’m happy for him. One of the Go-Go boys in the pictures also came to the show and told us that he and his husband now have two boys, and they still live in New York! I think it’s vital to remember that The Web provided a lot of job opportunities.

What kind of events happened at The Web?

Yukai Chen: Drag shows, ballrooms, and male pageants like the ones from the Asian Prince competition we included in the show. The pageants were the most popular, Mr. Chow hosted them monthly and hosted the Asian Mr. Prince. The Web also provided complimentary AIDS tests for the community, held countless informal same-sex weddings, and offered English lessons to help new immigrants adapt. Mr. Chow also told me there was a millionaire’s private club that rented The Web and its members put on drag performances for fundraising events, and Mr. Chow donated part of The Web’s revenues to the Chinese American Arts Council. It was also a “chosen family” for young people estranged from their biological homes.

Just yesterday, I was talking to the legendary New York drag performer Candy Samples, and I mentioned The Web. Candy told me that Jiggly Caliente used to work there.

Yukai Chen: Yes, she did! I was just talking to a photographer who took photos of The Web, and he remembered seeing Jiggly perform. He even found an image of Jiggly in Chun-Li costume!

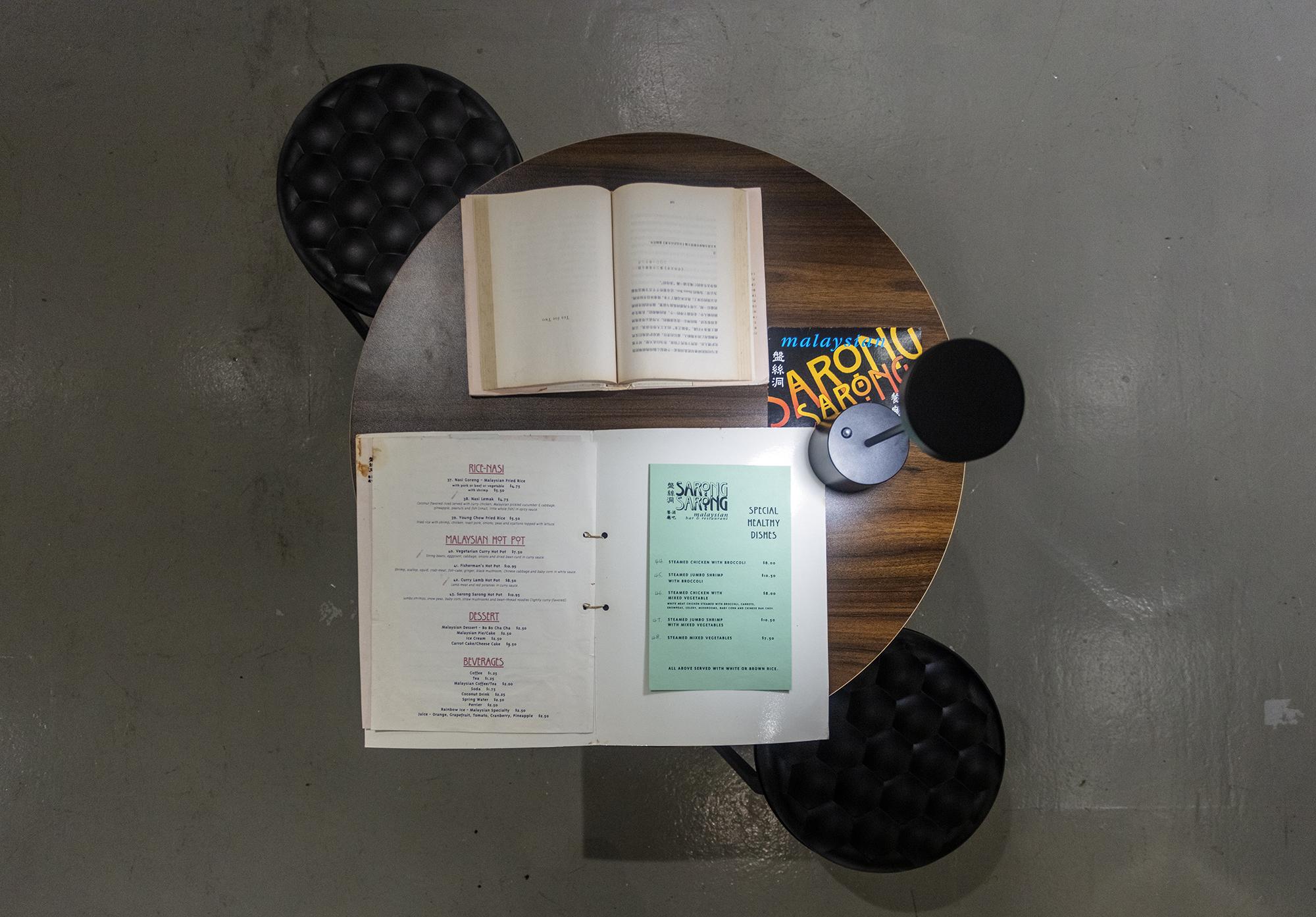

Incredible! And what was the connection between The Web and the restaurant Sarong Sarong? Although I never went to The Web I did eat at Sarong Sarong, because I worked nearby. The exhibition installation has the original menu.

Yukai Chen: Sarong Sarong was an extension of The Web, a Malaysian restaurant on Bleecker Street. Some people actually knew Sarong Sarong first before The Web.

Xiaojing designed the bar table area, and we all liked this idea. It mimics the scene of the restaurant, people can sit down and look through the menu and they can read the romantic story Tea For Two inspired by The Web, written by Pai Hsien-yung.

As curators, what did you want to communicate with this exhibition?

Xiaojing Zhu: What I wanted most was for the audience to feel what I felt when I first encountered the archives: pride. Using these documents to bring back those vivid days was my first instinct after hearing about The Web, its energy and its abrupt, regrettable, ending,

Yukai Chen: We want the exhibition to showcase the spirit of The Web. It was a unique anchor for Gay Asian immigrants, a place they called home. And we hope more people get to know it and get inspired by its rich history. The fact that it existed is already so powerful.

What was the process of making the photographic selections and building the installation?

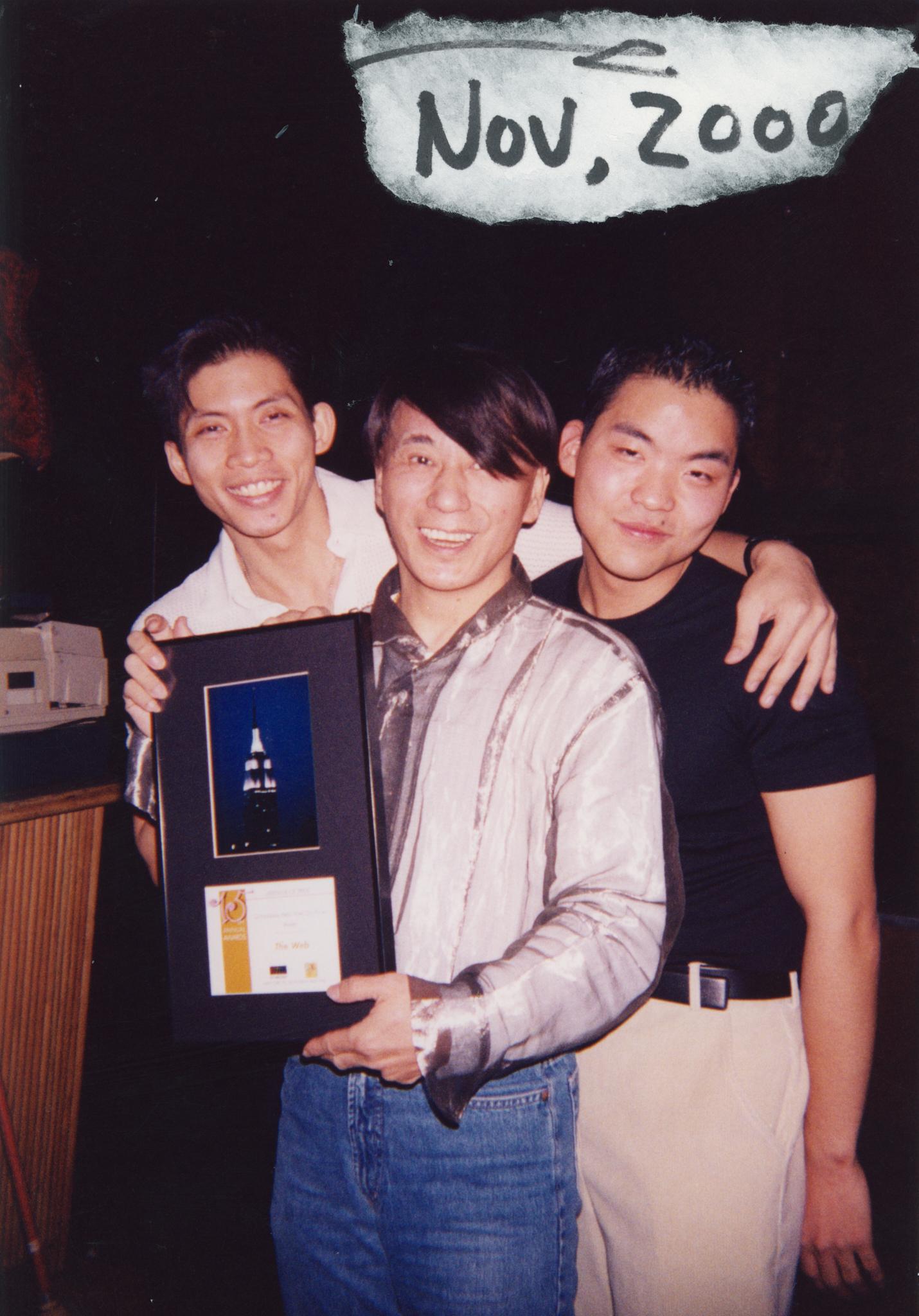

Yukai Chen: We really like the image of the handsome Go-Goy boy with the blue Speedo sitting at the Christmas theme stage. We used it for the zine cover. His gaze is so powerful and of course, his sculpted body is also fascinating. Mr. Chow told us he was a popular star at The Web, many people came just to see him.

Xiaojing Zhu: I used two wall-sized vinyl prints to shape the exhibition’s atmosphere.

Yukai Chen: One shows The Web’s float during 2001’s Pride Parade, the other presents the mural Chen Danqing painted in The Web’s basement, with Mr. Chow moving and the cameraman following. These two serve as openings of daytime and nighttime.

Xiaojing Zhu: At the first glance, you see a group of radiant, passionate, friendly, and proudly Asian Gay men dancing on the parade float. Turning right into the space you will see the bar tables and the mural painted by Chen Danqing. I hoped the installation could offer, even briefly, a sense of being there.

Yukai Chen: We divided the space into two main areas: the audience follows the route of The Web’s float from uptown to downtown Manhattan, where we also display the zines. Then they enter The Web’s nightlife scenes displayed in the middle room by Chen Danqing, and another area that showcases archival photographs of The Web’s nightlife.

What was it like going through Mr. Chow’s archive at the CAAC?

Xiaojing Zhu: I first learned about The Web from Mr. Chow. He rarely spoke about it, even though it inspired Bai Xianyong’s well-known story “Table for Two.” I read his book The New Yorker five years ago, and returning to the bar’s story felt like tracing a thread across time. In the exhibition, the table-for-two installation echoes that literary reference: not only as an atmospheric element but also as a place to display the archives. Together, I hope they make clear the bar’s layered character and its enduring legacy in the history of anti-discrimination and the Asian gay community.

These archives and people built visibility, solidarity, and culture long before such stories were widely acknowledged. The exhibition invites you to see their presence: inside a bar that became a home for a once marginalized group and gathered every member out on the Pride Parade. It’s a chapter of New York’s once veiled social history.

Hong Kong’s Sing Tao Daily featuring The Web’s New York City Gay & Lesbian Pride float on cover, 2007. Scanned and edited by Yukai Chen. Chinese American Arts Council Archives.

Yukai Chen: I first encountered the archives of The Web when I started working here. The fact that Mr. Chow, our Director, was once the owner of an Asian Gay bar really fascinated me. Then I learned more about his story: how, after finishing work at CAAC, he would drive Drag Queens to The Web; how he even donated part of his earnings from the bar to CAAC to support Chinese artists. These are such powerful, unexpected stories that deserve to be remembered.

Chen Danqing said something that really stayed with me: that Asian people are often reserved and shy, and The Web not only gave Queer people a sense of liberation but also other Asian people like him a sense of liberation. It showed him, and others like him, what freedom and self-expression could look like.

By bringing back the history of The Web, we want to celebrate its vibrant legacy and its contributions to the Asian community. But more than that, we hope the exhibition encourages people to think about the power of community—how people come together in the face of marginalization, and to imagine new spaces where every culture can co-exist and thrive.

The Web: The Birth and Legacy of New York’s First Asian Gay Bar is on view through December 5 at Chinese American Arts Council / Gallery 456, 456 Broadway, 3rd Floor, New York.