Marcela Guerrero Talks About Her Exhibition and the Whitney’s Expansion Into Latinx Art

On a humid September morning, I met with Marcela Guerrero, the first curator in the Whitney Museum of American Art to hail from Puerto Rico. We met over coffee at the museum’s café on the 7th floor. I wanted to speak to Guerrero about how she pulled off curating Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: indigenous space, modern architecture, new art less than a year after joining the museum’s curatorial team – most exhibitions take several years to plan – and, more importantly, the politics of her new appointment. With Latinx art in New York on the rise, institutions and curators need to be wary not to tokenize art or artists from the region.

Clarissa Tossin, Ch’u Mayaa, 2017, production still. Photograph courtesy the artist.

Upon entering Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay the viewer is met with a video made by Clarissa Tossin. It is an 18-minute video, which features the dancer Crystal Sepúlveda dancing to a set choreography in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House (built 1919–21) in Los Angeles. Responding to the Mayan inspired architecture, Sepúlveda wafts around the house using gestures and poses found in classic Mayan vase paintings, stone carvings and murals. The dancer’s movements serve as an exploration between her body and the built space, as dancers occupy the outside space as a defiant way of reclaiming it. The video work illustrates the artists’ syncretic approach to architecture; serving as a makeshift bridge between the ancient and the modern. An ongoing sound of pre-Columbian flutes and heartbeats accompanies this video as it infiltrates the rest of the galleries and makes its way through as the distinctive soundtrack of the exhibition.

Put together by Guerrero less than a year after joining the museum’s curatorial team, the ambitious exhibition features seven living artists: william cordova, Livia Corona Benjamin, Jorge Gonzalez, Guadalupe Maravilla, Claudia Peña Salinas, Ronny Quevedo, and Clarissa Tossin. Its premise grew from their common interest in the built environments and the natural world. Guerrero was particularly struck by the different ways in which these artists displayed a tendency to think about architecture in vernacular, and, at times, pre-Columbian ways. Their interest in Incan temples, constellations, ancient migration routes, all attest to their novel approach in revisiting the past.

Roughly, Pacha means time, space, and nature; llaqta means place, country, and community; and wasichay means to create and/or to construct a house in the Quechuan. The language is spoken by the Incas, the Huanaca, the Chanka and other indigenous communities of the Americas. Unlike the narrower and more technical terms used by westerners to describe architectural structures, Quechuan terminology emphasizes the ambiguity of space, the fact that it can both shape and be shaped. In this way, the Quechuan language understands space and how it is altered. As indicated by its Quechuan title, to describe the world and its structures in both nuanced yet manifold ways is, in turn, the central premise of this exhibition.

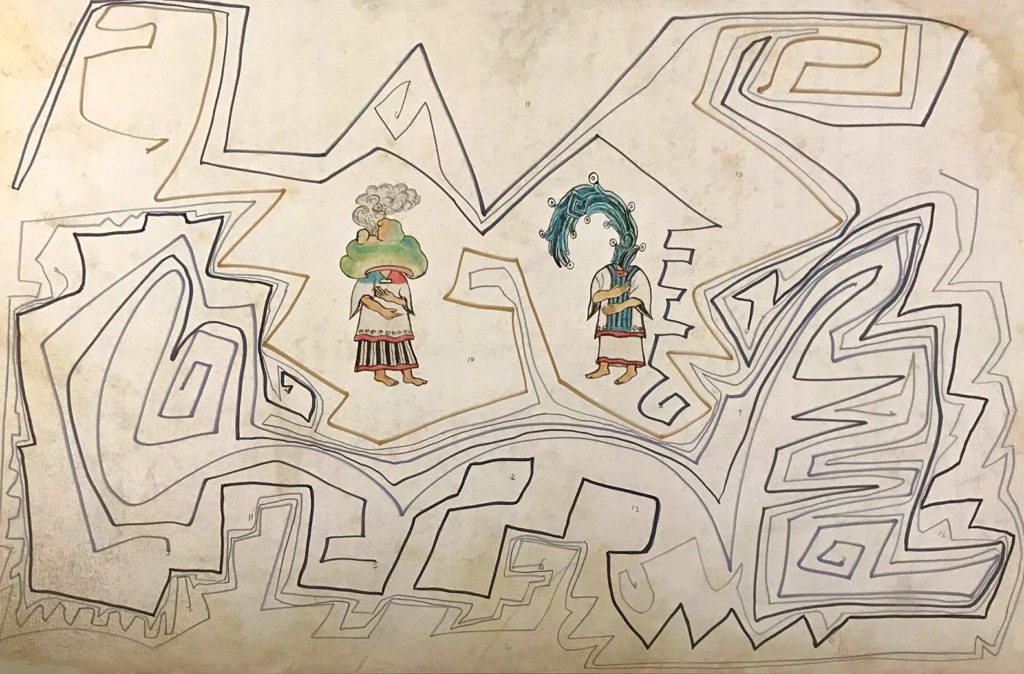

Guadalupe Maravilla, Requiem for my border crossing (Collaborative drawing between the undocumented) #9, 2018. Inkjet print with graphite pencil and ink, 20 × 30 in.

Guadalupe Maravilla’s drawings brilliantly explores migration routes. Inspired by a series of maps he found in a sixteenth-century Nahuatl manuscript, this piece explores pictographic symbols used in the manuscript’s maps and has drawn lines that are meant to be interpreted as immigration routes. Maravilla recreates the path he traversed as a child from El Salvador to the United States, creating parallels between the ancient conundrums and contemporary ones, where the sort of paradoxes come to be highlighted.

william cordova’s installation refers to Huaca Huantille, a temple built by the pre-Incan Ichma culture in what is now Lima, Peru. In cordova’s youth, the temple was home to displaced families who lived in improvised forms as they became homeless. This work, a site-specific wood scaffolding located in the outside patio of the Whitney alludes to this tragic story. The physical proximity of this work, which brushes against Renzo Piano’s concrete, creates –as Mary Louise Pratt describes- a ‘contact zone’. Of course, this gesture does not go unnoticed as cordova’s work bleeds into Piano’s building, clashing and grappling the architectural differences of chaotic wood to the sleek minimalist concrete.

Marcela Guerrero speaking about the exhibition in a video published on the museum’s Twitter account.

Leading the museum’s new initiative to advance Latinx art is a role Guerrero slips into perfectly, she was previously the curatorial fellow at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, where she worked on the ground-breaking exhibition “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985.” Reflecting the museum’s attempt to become a more inclusive and diverse space, her title – assistant curator – is not affiliated to her regional interests. “It is very progressive not calling my position a Latinx position as it avoids creating niches,” she tells me. She thinks that an interest in South American and Caribbean art should be the responsibility of all of the museum’s curators, not just hers. Conversely, Guerrero is certainly not prevented to work within other areas. However, it is under her guidance that the museum will carry out a systemic study of its Latin American collection in order to determine its gaps and blind spots and acquire new works along the way.

In that regard, Guerrero is not only interested in exhibition making and acquisitions; she is trying to make an impact that will change the way audiences interact with the institution. Ambitiously, she is trying to turn the museum into a bilingual space, a challenge which she tackles with great prowess in Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: indigenous space, modern architecture, new art.

…most of the canon of modernity in the U.S. comes from Europeans who later immigrated here.

-Marcela Guerrero

We must not forget that Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney founded the museum to showcase living American avant-garde artists; a group who had a very difficult time showing their work in the United States. The shift towards “the Americas,” allowed the museum to, like in its infancy, include artists who were underrepresented in museums in the United States. Today, the museum broadly defines its focus to be on artists “from the U.S.,” which is a term open to interpretation. For Guerrero, it means artists that live and work here. “If you think about it, most of the canon of modernity in the U.S. comes from Europeans who later immigrated here,” Guerrero pertinently comments. In a way, she explains, the Whitney has always been a museum of immigrants.

To talk about Latinx art is to talk about a history of differences and contradictions. Under this single umbrella term, a vast array of peoples and traditions are captured. This exhibition, however, pays heed to this difference, and rather than delimiting the term, it seeks to keep it open, putting before its viewers new and unexpected vistas of the past. Not all of the artists in this exhibition identify as indigenous. Instead, they mostly consider themselves of mixed race, or mestizos—descendants of both the colonizers and the colonized. Their emphatic use of the Latin American term, mestizo, in turn, contributes and questions current ideas of what it means to identify yourself in one or another way.

***

Exploring preservation of culture within converging civilizations, the installation by Jorge González talks about vernacular traditions, modernist architecture, and the art and culture of the Taíno—the civilization indigenous to the Caribbean islands. The roof is a modernist design popularized in Puerto Rico after the mid-twentieth century, while the walls are made of enea which was used in pre-Columbian huts. González’s installation honors the families that have preserved and disseminated indigenous techniques through architecture but also invites us to learn from them, asking viewers to participate in different readings and workshops throughout the exhibition.

As Marcela and I finish our conversation, she tells me that Jorge Gonzales is having a reading on the 5th floor and asks me if I want to join. Having already participated in a reading before, I accept. We headed downstairs. There was a woman dressed in a white t-shirt and white long skirt meditating to the voice of someone reading. I sat in silence next to Jorge and a group of about ten Puerto Ricans who had been invited to participate in this impromptu event. Marlène Ramírez–Cancio was reading Angelamaría Dávila’s poems from Animal Fiero y Tierno. Ramírez-Cancio’s voice broke as she paused and read:

Sera que uno no entiende

Que deshojarse a diario

No impide echar raices.

(Is it that we do not understand That defoliating daily does not prevent rooting)

She paused again, and read it once more, making sure that we all understood these words. We looked at one another and implicitly knew that this built space within this museum had allowed us to settle and root (if only briefly) in a place that was not ours. We had experienced a moment where Pacha, Llaqta, and Wasichay had occurred all at once, all together.

Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art (99 Gansevoort Street, Manhattan) through September 30.

On September 23rd at 3 pm artists from the exhibition will speak on a panel, tickets $10.

You Might Also Like

How Proxyco Gallery is Changing the Face of Latin American Art in New York

What's Your Reaction?

Juliana Steiner is a curator and educator based in New York via Bogotá. She co-founded Espacio Odeon, a contemporary arts center housed in an abandoned landmark movie theater located in the city center of Bogotá. She has worked in public programs and curatorial teams at MoMA, MoMA PS1, and No Longer Empty in New York. Steiner undertook her M.A. studies in Visual Art Administration at New York University. l Instagram