Shimmer as Protest, Music as Resistance: A Conversation with Théophylle Dcx on World AIDS Day 2025

Today is the first time since 1988 that the U.S. government is not recognizing and honoring World AIDS Day. Essential funding for medicine and research for HIV/AIDS, in the U.S. and abroad, has been slashed or cut completely by our current administration. It feels like I stepped into a time machine, back to Reagan’s first term, where the response to the AID’s epidemic was slow and the White House was silent. The lived experience of being HIV positive is not a relic from the past; it is one that men and women around the world still come to terms with and learn how to navigate. Marseille-based artist Théophylle Dcx is one of them. His work speaks directly to both his local and the global queer community’s past and future. It is intelligent, thoughtful, funny, and thought-provoking, and he has been able to take what was once a death sentence into a rallying cry of defiance.

In conjunction with our interview, Théophylle Dcx wrote to me, “Less information = death. Facism = death.” Chilling but true. Responding to the UNAIDS 2024 report estimates that there could be an additional 4.2 million AIDS-related deaths by 2029, he wrote: “mainstream media platforms dominated by the far right don’t care.” Artists might once again become more important as advocates for HIV/AIDS visibility. Through his engagement with archives, Dcx stands and soars on the shoulders of his queer HIV-positive forefathers and mothers. Read, resist, remember his words, and be activated to make a difference in your own community, not just today, but every day.

What is the one question you wish someone would ask you about you or your practice; and what is your answer?

‘What do you think about the relationship between the art world and the HIV/AIDS crisis?’

I feel that in France, this question has been largely pushed aside since the 2000s, when AIDS-related mortality decreased and the “AIDS years” came to be seen as over. Since “artists no longer die of AIDS,” the topic has become less visible in cultural spaces, leading to a gradual erasure of the issues associated with it — even though stigma persists, and may even be worsening due to a lack of information.

During Tête à queue de l’univers, I was talking with another artist Régis Samba-Kounzi about the fact that today, as the crisis risks worsening because of insufficient resources, one can wonder whether the art world will once again take an interest in HIV/AIDS, and whether such a renewed attention might carry a certain degree of hypocrisy. This raises questions about the tokenization of identities and the opportunistic use of activist topics by cultural institutions, which sometimes include them in their “CV” without any lasting commitment. Yet history reminds us that the AIDS crisis profoundly linked art and activism for more than two decades.

Perhaps art has remained important for AIDS advocacy since governmental support, across the board, remains inconsistent. “Undetectable = untransmittable” is a common public health message meaning that a person has a low viral load and can therefore not transmit, but it carries more weight for you.

I use undetectable as a metaphor for invisibility—comparing my HIV status to the undetectability of the fight today. Despite their parading of the red ribbon, mainstream media and politicians often obfuscate the struggles of immigrant, queer, and working-class HIV positive people, just like in the 1980s and 1990s. While the infection rate among youth in France aged 15 to 24 has increased by 41% between 2013 and 2024, disinformation is rampant in the same group: 40% think there’s a vaccine for AIDS and 42% believe you can be infected through a kiss. We live alongside a new generation that remains uninformed. One day is not enough.

You mentioned the group exhibition Tête à queue de l’univers at the art center La compagnie Belsunce, currently on view. This exhibition revolves around HIV/AIDS and coincides with World AIDS Day, including a full program of events exploring these issues throughout its duration. What are you showing?

In this exhibition, I present a series of oil pastel drawings depicting giant versions of Magic Cards from the Japanese trading card game Yu-Gi-Oh!. Magical, monsters, traps, and other cards that possessed real value in the schoolyard—traded, collected, and wagered—my drawings transform the cards into artifacts. They become symbolic tools for HIV treatment. Diverted from their playful origins, they take on new meaning, bridging imagination and care. The value of each card corresponds to the cost of the HIV treatments depicted, exposing economic inequalities and the power that money and social status confer over access to medication. I also play with the notion of undetectability: the titles and powers of the cards are etched into the pastel and only reveal themselves as the viewer approaches.

They are gorgeous. There are so many sophisticated HIV-treatments out there that remain unavailable to those who need them.

Big Pharma = death.

Tell me more.

I hope one day our countries will have the courage to tell Big Pharma to go to hell, and that trials like the one in Pretoria in 2001 will make headlines in our countries. When the South African government wanted to allow the import and production of generic HIV drugs, thirty-nine pharmaceutical companies attempted to block them. Big Pharma accused South Africa of violating their exclusive rights (lol-wtf). Faced with public mobilization and pressure, the companies withdrew their complaint in April 2001. This trial was a global turning point, paving the way for wider access to antiretroviral treatment in the country.

Today, situations like this still persist in Big Pharma. I attended a talk by Othman Mellouk, an activist for the right to access medicines, at La Compagnie in Marseille, where he urged us to put pressure on the major pharmaceutical companies, for example, regarding Lenacapvir, a long-acting injectable requiring only two doses a year. Developed by Gilead Sciences, it is a treatment that could be a game-changer in the fight against the epidemic, but the pharmaceutical prefers to sell it at an exorbitant price, around $40,000 per year, in “high-income countries,” even though the production cost could be between $25 and $40 per dose. They have been making headlines as it has come to light that they would allow the development of a generic version for “low and middle-income countries,” but will exclude countries that participated in clinical trials, which also happen to be the most affected, from access, thus limiting its impact.

Gilead protects the treatment with a multitude of bullshits patents to maximize their profits and maintain exclusivity. They ignore the epidemic, and they slow down market launches or collaborations to keep all the benefits for themselves. It’s incomprehensible: more than forty years after the AIDS epidemic, how can Big Pharma act with complete impunity, refusing access to science?

Last week, Emmanuel Macron was in Johannesburg for the G20 at the same time as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria conference was held. France has not yet renewed its financial contribution to the latter. We need treatments that are accessible to everyone, everywhere, without geographical or economic distinction.

Preach. You are also doing a residency right now.

The residency I’m currently doing is a performance project with my artist and DJ friend Laju Bourgain, which is to be presented as a work-in-progress at the Parallèle festival in Marseille. It’s a dance piece and our first duo. In this project, we draw inspiration from the choreographic phenomenon of the Macarena—a dance whose steps are embedded in the bodies of multiple generations, crossing social and cultural borders. In our performance, we appropriate, transform, and exhaust the Macarena’s movements, exploring their unifying power and hypnotic mechanics. Through relentless repetition, we question bodily memory and the affects tied to these standardized gestures. By synchronizing, repeating, and exhausting these movements from popular culture, we seek to reveal the invisible threads that run through bodies, uniting and differentiating them.

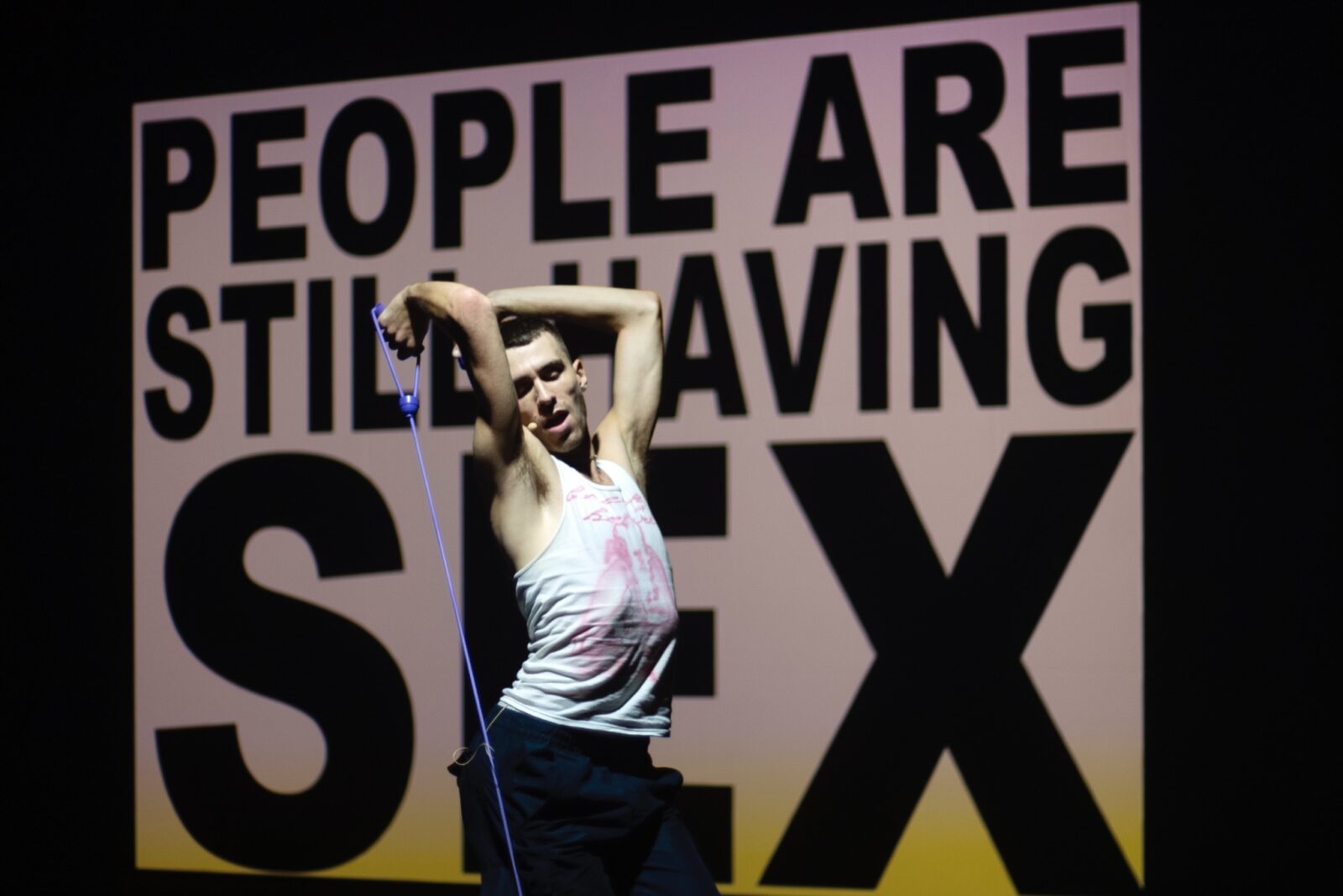

One of the things I love so much about your practice is how important music is, in particular to history and community. In your duet performance piece with Maria Silk, On the Floor (2025), presented in San Francisco, queer legacies, 1980s nightlife music, and the legacy of HIV/AIDS is central. What was it like performing this piece and what did you discover during your research that surprised you?

Last year, I had the opportunity to do an artistic research trip to San Francisco, focusing on the dance music scene from the late 1970s to the early 1980s and its connections to the HIV/AIDS crisis. There, I met Maria, who is pursuing her PhD at UC Berkeley, and we discovered many similarities between our respective research projects. We decided to work on a collaborative performance together.

The creation process took place at CounterPulse Theater, which hosted us for a residency as part of their ARC Edge program. We presented a work-in-progress showing during their annual festival in September.

Both of us were experimenting for the first time choreographic and dance performance. We brought our ideas, archival images, music, and research threads that we wanted to interpret on stage. We explored how to translate our research through this music and the HIV/AIDS crisis that shaped it. The most surprising aspects of this research were the encounters with former DJs, dancers, party organizers, and anonymous individuals who shared their archives and stories with us; they were beautiful moments. Also browsing into archives video collections at the glbt’s archives where I spent hours.

Your practice heavily dives into research and looking at archives, something that I myself am personally drawn to. Tell me more about how research takes part in your practice, in particular, the history and experience of HIV/AIDS in the queer community.

The archives I use in my projects are multiple. My research can lead me to institutional archives like archive centers, universities, public collections, but I also work with private and personal archives, internet/social media archives, as well as oral histories—when I meet people connected to my research. In several parts of my work, I try to link a certain intimacy to collective memory and it’s essential to me to use this material.

Working and researching with archives allows me to trace genealogies and small constellations on my own scale, in order to connect our memories and situate where they belong, to fight against erasure and to inscribe others into a new collective memory (body). What interests me about archives is the echo they produce in the present, revealing the cracks in the progress we are led to believe in.

Today, I feel like I could live what the archives tell us, when we see budget cuts in the fight against HIV/AIDS, when we see LGBTQ+ rights being rolled back, and the general climate of fascism that no longer bothers to hide.

Besides making emotionally charged and researched performance work, you also draw and create sculptures. One of the sculptural works that is on display now in Marseille are disco balls you created for your first solo show in Tokyo, “undetectable bodies.” What was your experience exhibiting and creating work in Japan? A place where hiding is prescient.

The exhibition in Tokyo was an incredible experience. The relationship to HIV is even more taboo there than in France or in the US. I felt a perhaps more attentive interest from the public, since the issue remains discreet, the stigma possibly more violent, and marginalization perhaps more likely. In a way, I found it even more important to show my work in this context.

The title “Undetectable Bodies” had been chosen in advance with the two curators, and as often happens, I had last-minute doubts. But once I was there, my doubts completely vanished as I confronted the reality and realized how crucial it is to talk about HIV/AIDS all the time—and how the undetectability of bodies and struggles stems from an oppressive system, the medical establishment, misinformation, and the absence of memory work. It’s impossible to learn everything alone.

Wow. And, what are the text fragments on the disco balls?

The chandelier is made of ceramic disco balls, elevated to the status of luminous relics. Engraved on them are fragments of lyrics from Patrick Cowley’s song “Going Home,” released a few months before his AIDS-related death in 1982. Cowley was a main figure in the 1970s and early 1980s on the dance/high energy/disco scene. His work resonates as a sonic memorial to queer desire, loss, and survival in the shadow of the HIV/AIDS crisis. Slowly rotating, these ceramic balls become both memories and keepers of history. Their glow, baked into the ceramic, illuminates part of this story and the vanished voices of those dance floors, as well as those who still sing today.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

You Might Also Like

What's Your Reaction?

Alexandria Deters is a queer femme embroidery artist, researcher, activist, archivist, and writer based in the Bronx, NY. She received a BA in Art History and in Women and Gender Studies at San Francisco State University in 2015 and her MA in American Fine and Decorative Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art, NY in 2016. Her writing and artwork are influenced by her belief that every human being is a ‘living archive’, a unique individual that has experiences and stories worth documenting and remembering. Photo: Ross Collab. l Instagram l Website l