Twitter Celebrates Black History Month on #AWallforACause: An Interview with Dominique Duroseau

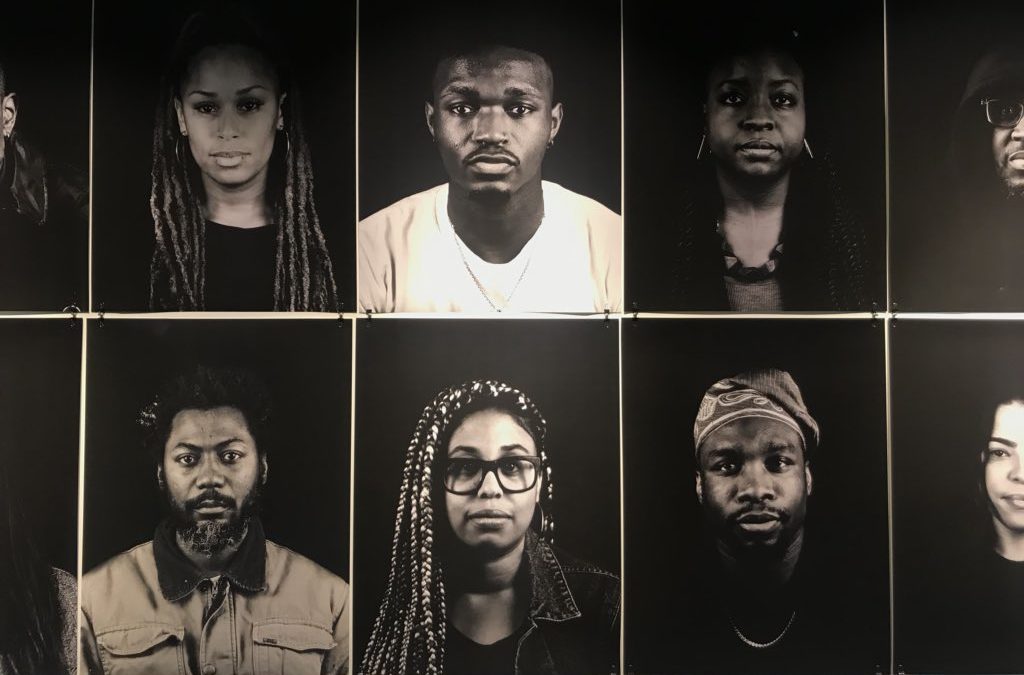

To celebrate Black History Month, social media giant Twitter commissioned the Haitian-born American artist Dominique Duroseau to create an iteration of her series “Black Face Index.” With just the right mix of thought-provocation, around the issue of a race, and celebration to fit the corporate environment, the show presents forty portraits of Twitter employees of color. The works were on view on #AWallForACause which is dedicated to presenting work by local artist’s that highlight social causes. The wall, situated in Twitter’s New York office in Chelsea, is not accessible to the public but Twitter held several events open to the art community and friends.

The project was initiated by Blackbirds, Art Noir, and Ariel Adkins, Twitter’s Arts and Culture Liason. With 217k followers, @BlackBirds is a Twitter account run by Twitter’s employee resource group that promotes diversity, all year round. There is talk that “Black Face Index” might travel to San Francisco, where it would be open to the public. With a wider reach, this would be a good opportunity for Twitter to publicly celebrate diversity through art.

Duroseau has been working with “Black Face Index” for the past decade. At the core of the series is her will to humanize the black body, to get the public to look at black people as friends and not threats. The artist first sat black people down to take their portraits during a residency that she titled “The Lime Sessions,” at Index Art Center in her hometown Newark, New Jersey. She has taken 90 portraits since, and will continue.

To highlight the importance of continuing the conversations that Black History Month generates, Cultbytes decided to sit down with Duroseau to discuss the importance of “Black Face Index” at Twitter and how to continue to observe and promote Black artists past February.

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand, Editor-in-Chief, Cultbytes: Who are the people in “Black Face Index”? What were their reactions to the project?

Dominique Duroseau, artist: They are people — specifically, black people. They are people more likely to be profiled. They are friends, strangers, co-workers. The person teaching your children, cleaning your offices, cooking your food, guarding you. They are lesbians, gays, straight, trans. They are educated, they are uneducated, well-off, struggling to make ends meet — the person who is most at risk of being killed and most likely to be accused of being a criminal, just at a glance.

The subjects’ reaction to the project is to be part of it, to be supportive — but when they see themselves, it’s much stronger. It’s a shift; because there is a psychological manipulation in how I want other people to see them, they can see what I’ve done and, at times, can’t believe that it’s actually them up there.

Above, previous: Dominique Duroseau, “Black Face Index,” Twitter New York. Photograph courtesy of Black Enterprise.

Above, previous: Dominique Duroseau, “Black Face Index,” Twitter New York. Photograph courtesy of Black Enterprise.

Why is it important that “Black Face Index” is on view at Twitter’s HQ in NYC?

I can’t speak on corporate culture, because I confess I’m not well versed, but I know diversity has always been an issue in many corporate fields and — coming from an architectural background myself — the number of people of color who start these programs is already disproportionately low by comparison. By the time you graduate, these numbers drop exponentially, more so than through the standard attrition, stress and workload that whittle down the class sizes. The worst is trying to find employment afterward; I can’t tell you how many people I went to school with who studied Computer Science, Information Technology, Architecture, Graphic Design, Pre-Med, Engineering, Bioengineering, and managed to graduate, yet are now bus drivers, security guards, Uber drivers, or doing something completely out of the field they studied, because they can’t get a job — yet many were at the top of their class.

Dominique Duroseau, “Black Face Index,” Twitter New York, 2018. Clockwise from left, Dominique Duroseau, Larry Osseih-Mensah, Stew Cornelius, and another Twitter employee. Photograph courtesy of Robin Cembalest.

Dominique Duroseau, “Black Face Index,” Twitter New York, 2018. Clockwise from left, Dominique Duroseau, Larry Osseih-Mensah, Stew Cornelius, and another Twitter employee. Photograph courtesy of Robin Cembalest.

My point is that their visibility today at Twitter’s HQ — those black people’s visibility — is shocking and overwhelming to many of us, and in a good way. It was shocking to me because I didn’t believe it actually existed, that — yes! — we could really see ourselves in these spaces, in these roles. More importantly, it’s a discourse of black presence in a white space. It’s about — for a moment — the “others” can celebrate their peers. It’s about reminding them (non-people of color) how the people on this wall — some of whom they may know or recognize — outside of these walls are perpetually in danger because they are seen as a threat at first glance. And, because of this revelation, it hopes to ask the viewers, “What will you do to shift this mentality?”

I really like that that “Black Face Index” is both celebratory AND thought provoking. Now that the show at Twitter is reaching its end, in what way do you think “Black Face Index” on the #WallForaCause impacted employees at Twitter?

It’s true what they say, “Location is everything.” The #WallForACause is located in a lounge space connecting the cafeteria with the elevator lobby and various workspaces. This means that by now most of the employees, guests — anyone’s who’s been coming in and out for food or drinks — will have seen the piece. I’m sure it’s been discussed and questioned and, while I can’t be sure of this but I’m purely going on experience here, I’m certain at least a few probably were wondering why only black people were in the photos. Mainly, I pray the impact is a seed. At most, the impact is that: loving themselves, celebrating each other for a moment, having questions, questioning “possible inner racism” privately, getting familiar with the idea of the importance of visibility of black people as equals, as leaders… that they’re more than just janitors, cooks, security guards.

when the public becomes a part of this experience as well as those representing Twitter’s SF offices, the impact on perceptions and black visibility can be that much greater.

-Dominique Duroseau

Judging by the ear-to-ear grin Stew Cornelius gave me when I talked to him about sitting for his portrait during the show’s install, I would say it incited pride, in the most positive of ways. Will “Black Face Index” travel to San Francisco? How would you envision this collaboration continuing with Twitter?

I have to express thanks to Larry Ossei-Mensah (curator through ArtNoir, which he co-founded) and Ariel Adkins (Twitter NYC’s Art & Culture Liaison) for bringing all this together in the first place. It really was accomplished within a short time but Larry believed in me, in the work, and knew I could deliver, so we set those days up and made the magic happen. In the process, there was mentioned the potential for a follow-up in SF; right now everything is in hopes and in discussion. The New York Twitter employees and their invited black friends had this transformative experience, despite it being contained within a corporate loft. The San Francisco office has a semi-public space, where I’d like to set up — when the public becomes a part of this experience as well as those representing Twitter’s SF offices, the impact on perceptions and black visibility can be that much greater.

What are the most important aspects of Black History Month? And, in what ways, if any, is Black History Month complicated?

Black History Month is complex for black artists. It tends to be the time you get called on when things have been quiet. One thing I’ve discussed at length with my performance artist partner-in-crime Ayana Evans is the flood of poorly-planned, thrown-together curated shows during that period; and therein lies the real issue. What’s equally challenging is balancing this “game” with the artist’s need for visibility/opportunities and with the actual importance of Black History Month — which is more than a hashtag or a theme; it’s a mission. Celebrating Black History is about bringing forth information buried, celebrating who we are, and in the context of art we get to experience the legacies of said history and how we are connected from one black culture to another. I honestly believe Black History Month needs more thought, care, research, better programming, and exhibitions with strong concepts, works, by good artists.

The benefit of art is its fluidity; unlike a workplace the obstacles aren’t as prominent when politics and art are merged.

-Dominique Duroseau

What conversations need to continue after Black History Month in the workplace and beyond?

If black artists are brought in to show work, perform work, engage in artist talks around that time, this tells me there is a need for discourse around that topic. Don’t end it there. Do not use those artists as your token for a “diversity” community building project then close the book. Invest in creating more exposure and different ways of having these discourses in the workplace. The benefit of art is its fluidity; unlike a workplace the obstacles aren’t as prominent when politics and art are merged. Depending on the exhibition or topic for panel discussion, tension may exist, but the atmosphere is not like a work environment that abides by strict rules, with this inability to communicate freely, it’s the opposite. It would be of benefit to collaborate more with the artists on their level, to be able to have some of these conversations.

You were born in Chicago but primarily raised in Haiti. How did the conversation on race affect you when you returned to the US for your studies?

…it was definitely a shift. I went from living in a colorist, classist, colonialist society with deep indirect racial issues to a straight-up racist society. If I’m going to be honest, the U.S. houses the gamut of all social issues, but it’s the difference of, in Haiti, worrying about being judged or vetted by the persistent queries: “what’s your last name, where do you live, where do you go to school” — to, in the U.S., walking into a store and being followed and asked “can I help you?” a million times and not being the only customer present. Being a black woman in architecture school was really when I understood how deeply ingrained and complex racism could be. I was tormented indirectly: I had no allies, no one to complain to, no one to vouch for me, no proof….what’s worse, I couldn’t fight the racism nor the sexism; I needed to focus on the challenging schoolwork I would constantly have to redo last-minute to avoid failing. I had a teacher who would talk down to me in front of everyone — mind you, I was the only female in the class. One time, I was out due to a dental surgery; against my doctors recommendations, I went back to class to take his test because I knew he wouldn’t believe me. He looked at me, asked if I could talk, I shook my head no. He said: “Try!” Then shouted: “ORAL test today!” and smirked at me. Not only was I in pain the whole time, drooling, he failed me. My freshman class started with about 180 students, less than 15 were black. Two black architecture students graduated the five year program, and I’m one of them. Then, after graduating, I couldn’t find a job.

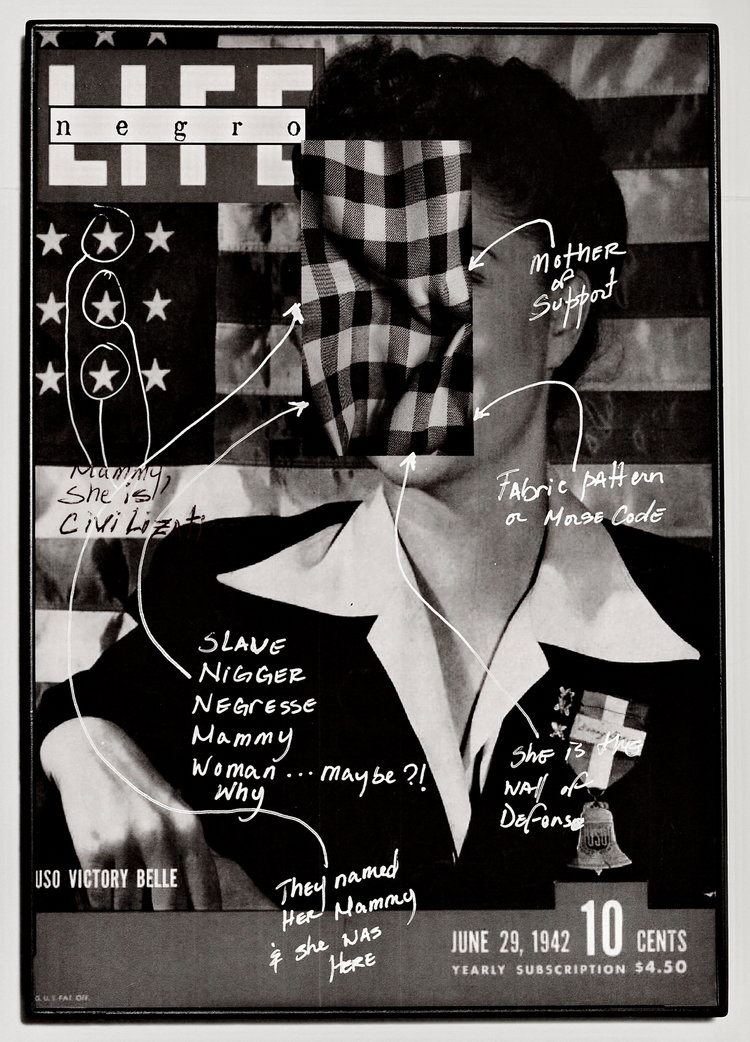

Domonique Duroseau, Mammy Was Here, 2016.

Domonique Duroseau, Mammy Was Here, 2016.

That’s terrible but unfortunately not uncommon. The threshold for black talent to get into corporate jobs is, unjustly, often much higher than for White or Asian. I think your series partially inspires this to change. BlackBirds and ArtNoir invited you to create this iteration of your portrait series at Twitter. What are your ideas on collaboration in terms of raising awareness for black artists?

Collaboration is a willingness to trust in each other, first and foremost; from there the ideas can be endless, especially with a good match. I curated an all-day performance exhibition at the Newark Museum, with the majority of the artists being black artists, and was exhibiting at Smack Mellon — I was to perform “Rap on Race with Rice.” I thought it was very important to be selective of my participants, so they could share this opportunity. Of course, sometimes you might have a project or idea and the persons you have in mind to work with might not be available or interested. There are other ways to work/collaborate with Black Artists aside from curating: write about each other (we need more thoughtful write ups), apply to a short residency with someone as a collaboration, invite each other to do panel discussions, or just go old-fashion and work with each other. If opportunity presents itself great, but everyone has odd schedules and sometimes it doesn’t.

In short, promote and work with each other when you can. What should curators be wary about as they attempt to curate diverse and inclusionary shows?

If you’re a curator, gallerist or writer in search for diverse artists doing certain work, my best advice is to ask other artists. And, to those claiming “diversity” when they clearly aren’t, no one is buying it…the numbers, the bodies, don’t lie.

Your sculptural and photography-based work sheds light on the black body from different perspectives. In the works included in your solo show “Black Things in White Spaces” at Gallery Aferro you explored racist glamorized stereotypes of blackness. In an article in Hyperallergic, the critic Seph Rodney called your presentations of the body, or body parts “negrofied,” as the installations highlighted ethnic markers. These sinister works made with mannequins, garbage bags, plastic flowers, and black tape, among other things paint a dark disjointed picture of the perceived black body. Conversely, “Black Face Index” at Twitter presents its viewers with personalities, or bodies with agency. In each portrait you have positioned your subject in the same lighting within the frame in the same way and yet each is so different. As a viewer, I am led to imagine who the people are, using dress, hair, jewelry, facial expressions as clues. In both series, your interest in de-contextualizing/contextualizing/re-contextualizing is at work. In what way are these different series connected?

At its very core, it’s existentially focused on Black People. The connection is subject, who am I trying to discuss, the persistent issues that I find to be connected elements/nodes from one black culture to another. The portrait series acts as a counterpart or partner to the sculptures… the best way to explain it: the sculptures reveal a reality people don’t want to face. Some people like to pretend some issues are no longer a thing or they are shocked/in disbelief when they are exposed to something they’ve “never heard before.” Then, there’s this need to deny it or to tell a story how they used to live/do good for black people, and were chased away, to claim it’s not only Black People dealing with these issues. The sculptures choose not to play those games… they hit hard, they hit nerves, they make you uncomfortable, they externalize ugliness done to society. They document, demonstrate a condition that is gritty, and at times it can be painfully beautiful (not always). They’re never portrayed as whole bodies because I don’t believe we are, due to so much wear and tear mentally and physically taking a toll; I needed to conceptually match this, and it’s a way to emphasize social dehumanization. The photographs also do not show a full body; what’s essential is their face, their eyes, their expression. I am talking about real people at this point… no longer an assumed figure representing many (sculpture) but actual people who have lives, lived, been discriminated against, are in danger, and need their faces to be seen clearly for what they are… human beings.

Dominique Duroseau, “A Rap on Race with Rice,” at “Your Decolonizing Toolkit,” at MAW, New York, 2016.

Dominique Duroseau, “A Rap on Race with Rice,” at “Your Decolonizing Toolkit,” at MAW, New York, 2016.

In the performance work “A Rap on Race with Rice” you invite audience members to sit with you to discuss race while separating white rice from black rice. Why is this work important?

This piece was inspired by the famous 7.5-hour conversation between cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead and the writer and social critic James Baldwin, entitled “A Rap on Race,” recorded in 1970. The idea of two people carrying on a series of emotional rollercoaster conversations — while maintaining respect for each other’s point of view — was, for the time, so incredulous and very astonishing. It’s still needed today; I needed to find a way to make that happen with some form and fluidity — this is where performance is important. The separation action acts like hypnosis while the conversations get shaped around you. I won’t lie, the piece plays tricks on you… you’re not expecting that moving rice as people talk could do anything, but a few things have happened to date: people got to think about things that they haven’t thought about in a while, or ever; it has hit nerves; it has stunned a few in shock and they stopped talking, just pensive the whole time; et cetera… I personally think the piece is important because it removes people out of their personal comfort zone for just a moment. You also can’t tell if it’s a game, talk, whatever… it acts like a honey trap for that moment… and just like that, we’re in your head.

Dominique Duroseau, “Mammy Was Here: Into The Stillness” Newark Museum, 2016. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Dominique Duroseau, “Mammy Was Here: Into The Stillness” Newark Museum, 2016. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

In contrast to “Rap on Race with Rice” which is interactive, “Mammy Was Here” is, in a way, disruptive and in it you do not at all interface with the audience. What is this piece about?

Yes, it is, however each piece interfaces with its audience very differently. “Mammy Was Here” has interacted with her audience in performance, just not in the same manner as “Rap on Race with Rice.” The “Mammy” series is both simple and complex; she can be soothing or a lingering discomfort. She (the series) bridges past and present women, Black Women, Women of Color, and Men. She’s the one always domesticated, with or without an education, treated like she’s the maid, while wearing a power suit. She is the Black man guarding the building, sweeping floors, bussing tables, driving buses with a degree. She’s the one perceived to have an unpleasant body to touch or look at, but good enough to get their comfort fix; she’s generations of women who work tirelessly investing in their children to do better, only to have the system slam them back in the same position; she is what the endless cyclical socially degrading rigged system looks like, and her name is — still — Mammy.

I really love the intensity in which you performa Mammy. She always gets my mind racing. What will you be working on after the exhibition closes?

I’m finishing new works for my upcoming solo at A.I.R. Gallery in April. Super excited about that one! I just got into a Wassaic Project residency… looking forward to that time to develop abstract “Black on Black” works that are kin to the Black Portraits. The concept has been in development for as long as the portrait series, it’s this idea of fusing blackness; different black things becoming a series of units, in other words a unified panel of 10 to 12 Black things. Without revealing too much, I want to address the fissures among Black People, and how to get them to recognize themselves in each other. I want to explore the viewing experience of the Black Persons as a grid on a wall. First you search for someone you know, the more you look – you’re looking at their eyes, nose, lips, face structure – you start to think, this person reminds me of blank… and that’s how we flatten false senseless need of hierarchy, unnecessary hate between us, and mend the fissures. I can’t wait to see how this might look as an abstract tableaux…it might be crap, but it might be dope… for now, I’m excited I’ll have the time to explore it.

It sounds dope to me! I look forward to seeing what new facets these abstractions will highlight. Thank you for taking the time to chat.

Dominique Duroseau’s show at A.I.R. Gallery is opens April 19th and runs through May 20th, 2018. A.I.R. Gallery, 155 Plymouth St, Brooklyn, NY 11201.

Related Articles

“Your Decolonizing Toolkit:” Freeing Thought From Conditions of Exploit, Patricia Silva.

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.