Claudia Doring Baez and Ellen Frances 1950s Nostalgia

Upon entering Claudia Doring Baez’s apartment in Tribeca her husband greets us warmly. They live in The American Thread building—built in 1896 but converted in 1980 to luxury condos—it is located on the corner of West Broadway and Beech. I arrive together with Baez Doring’s gallerist Mattias Tönnheim, “she is like a sister to me” he explained warmly on the cab ride over. She is hosting a lasagna party to celebrate her participation in VOLTA with Mattias’ Marbella-based gallery Wadström Tönnheim Gallery. Air kisses and cheer abound with this chic crowd. There is art from floor to ceiling in the appointed entrance with a tiled floor framed by a Greek key design. After I am served a glass of champagne I ask her husband, a well-dressed Nicaraguan gentleman with a good mane of hair in a suit, where his wife’s work is. “Wonderful. I will show you. All along that wall,” he gestures fondly and excitedly into their sitting room.

Doring Baez has lived in New York for over forty years. But, she was born and raised in Mexico City. As her mother was a painter, she grew up around artists but it was not until they visited Robin Bond’s studio in Tacubaya—west-central Mexico City—that she became hooked on painting. ‘Meta’ and ‘close-looking’ are two words that can describe the nature of Doring Baez’s practice. Often she quotes other works of art, or begins her line of inquiry from an artwork albeit in another medium—books or a film, for example. In the two-person show “Raw & Cooked” at LaMaMa Gallery in 2021, Alain Resnais’ “Last Year at Marienbad” served as inspiration—“Baez’s images are intimate, redolent, full of both mystery and yearning. Baez has once again performed the alchemy of filtering known imagery through her own personal perspective—adding an enticing and visually loaded layer,” writes Phoebe Hoban in a review. Armed with a bachelor’s degree in film from Columbia University it makes sense that Baez Doring would enjoy bringing a new perspective—her reading or memory of—Resnais’ self-referential and layered New Wave cult classic.

“Have you seen Claudia?” I hear people asking at the party. Both friends from the city and neighbors from Quogue on the South Fork of Long Island where the Baez’s have a vacation home form the crowd. “Quogue is quieter than the rest of the Hamptons,” says a party-goer and neighbor who is also a publisher at Art in America. Soon I bump into the hostess—she is warm and vibrant. “Did I show you my Robert Maplethorpe? Or, no…” she trails off. “Motherwell!” I offer. We laugh. A lovely Motherwell stands on an easel. Artists usually have the most interesting art collections; artworks by friends and artists they love and admire. Baez Doring is no exception. “Did you see Matias Di Carlo’s works?” she says as she points towards the metal sculptures placed in various corners and on the coffee table. The Spanish artist is also showing with Wadström Tönnheim Gallery at VOLTA, and is a friend of the painter, so for Baez Doring who I immediately sense is inclusive and generous, he is also being celebrated.

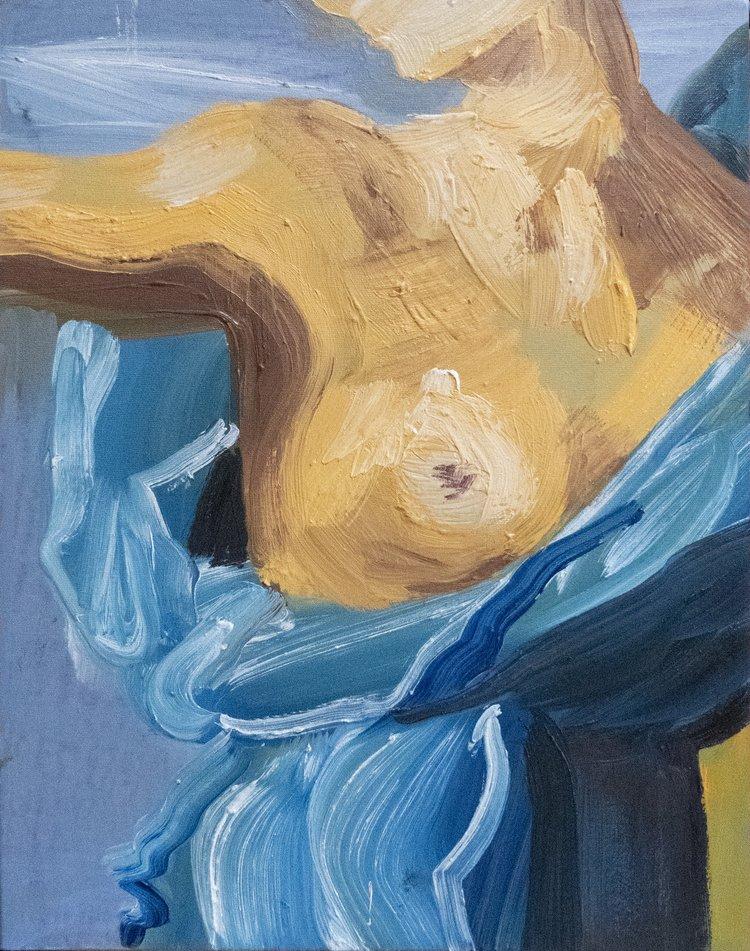

In 2022, Doring Baez shared a booth at the Mexico-city art fair Zona Maco with her brother Adolfo Doring, a filmmaker and photographer curated by her daughter Alexandra Zelman-Doring of The Empty Circle. Cheekily titled, “Old Masters.” Doring Baez’s works look toward the true art historical meaning of Old Masters as she has recreated elements from works by Nicolas Poussin, Jacques-Louis David, and French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix, often seen as the last Old Master painter. Doring Baez work’s has a caught-in-the-act and sometimes sexual undertone; her interpretation of Poussin reveals a woman’s breast and nipple. “Delacroix’s Horse in the Death of Sardanapale” offers viewers a close-up of the horse that in the original painting is watching the chaotic scene of death and violence; severed from the scene, narrowing feelings, it’s voyeuristic, fateful, and fearful elements become more apparant. Doring Baez has used brighter paints—ochres—and the brushstrokes are thick and the paint laid heavy at certain parts—bringing Delacroix’s loose brushstrokes to the extreme. While Doring’s nostalgic photographs and stills allude to masters closer in history with shots from his 90’s music videos of Lauryn Hill and Dixie Chicks, alongside composite diptychs of sultry women and foodstuffs, a dog in a car. But perhaps, most prescient is that the siblings are the ‘old masters’ themselves.

This year at Zona Maco Doring Beaz was nominated for the Tequila 1800 Collection award which drew attention to her work. “My booth was full at all times,” she tells me when we met a couple of days after her lasagna party now in the café at VOLTA to speak more about her work. Fittingly, the series she showed at Zona Maco depicted Mexico—ranging from pyramids and natural landscapes to its people. Explaining how she appropriates the work of others, she says: “I use an image as a reference, then I take liberty with it. What was the photographer trying to grasp?” One such reference is the Mexican photographer Manuela Alvarez Bravo and his former student Graciela Iturbide (who in turn has made works that reference the work of Frida Kahlo). Iturbide is an artist in her own right, “she taught my brother how to photograph,” Doring Baez continues to weave the story of interlinking relationships and repeating imagery. Eva Sulzer, a Mexican surrealist, also serves as an inspiration. “I used their images, but I found the things that I grew up with in their work making it my own.”

“You are not an artist if you do not go to work every day,” she tells me. “Except if you are at a fair, then you eat and drink and show yourself,” we both laugh. Speaking to Doring Baez whose willpower is great and energy is high makes my fair fatigue subside. Her studio is in Gowanus, which also shares space with The Empty Circle, where her daughter, involved in theater, organizes performances on occasion, and her husband, a clarinet player, also stages projects. Like when she grew up in Mexico City, she is now also surrounded by creativity in her family and in her inner circle. In 2016, Doring Baez photographer brother passed away after a four-year battle with lymphoma. “We were constantly conversing, producing, comparing, and discussing our work,” she says about him.

After his death, she decided to move her studio from Manhattan to Brooklyn to be closer to her daughter and grandchildren. She also wanted to do something for her brother’s friend and curator Raul Zamudio who needed a gallery space. “Before you go around giving keys to everyone, let me formulate a plan,” Alexandra told her mother. Upon finding the space, her daughter devised a sharing schematic for the studio-cum-project space. The Empty Circle hosts Zamudio’s gallery half of the year and on occasion serves as a venue for performances and concerts while Claudia has a permanent studio in the back—offering her both the calm to work but also the company of family and friends on a semi-regular basis.

When I ask what she has brought into her painting practice for film, she says that she has long been interested in the distinctions between the long shot, medium shot, and close-up. Her “Old Masters” series employs the close-up. As subject matter film is ever present, in addition to Resnais’ “Last Year in Marienbad” she has also painted work responding to Andrei Tarkovsky, and Stanley Kubrick, and she is working on a series responding to Pedro Almodovar’s films—they will be shown in two different exhibitions in Mexico later this year.

At VOLTA, Doring Baez is showing a series influenced by the seminal book “The Americans” (1958) a compilation of 83 photographs chronicling Swiss emigre and photographer Robert Frank’s 10,000-mile journey through the country; revealing regular Americans deeply affected by classism, racism, and poor governance. Frank arrived in America in 1947—”in my eyes this Swiss man is trying to figure out who the Americans are, which is priceless, as I am also an outsider,” Doring Baez explains her choice of subject matter. Jack Kerouac wrote the introduction to the book, stating that Frank “sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film.” In the Cold War era where images from Hollywood inspired the public, Frank’s photojournalism portrayed a rawer view of people navigating disparities in the country. “What he considered was American really speaks to me,” she continues.

The works Wadström Tönnheim Gallery has chosen to show in their booth at VOLTA are both timeless and iconic images of American life—a highway, a political rally, a navy recruitment station— images that conjure contemporary life and concerns. Others are frozen in time, a drive-in movie theater and a post box, telling of industries in flux and crisis being replaced by new technology. Based on decisions across party lines, thousands of USPS mailboxes have been removed as people turn to digital forms of communication. Drive-in cinemas are more of a novelty than a norm since the arrival of streaming services. Starkly contrasting the photographs she uses as references, the painter employs strong colors and broad brushstrokes. Rather than stills, her paintings render the images topsy-turvy, almost moving.

On Saturday, against the backdrop of these interpreted paintings of photographs of 1950s American life by Doring Baez, Ellen Frances staged three performances. At 4PM she delivered a poetic ‘movement monologue’ about a bygone era cityscape. Wearing a vintage suit from the 1950s she narrated a scene to the audience describing lampposts lighting the streets and women and orphans moving through the city—tears streaming down their faces. A dancer observing the city of New York at the turn of the century perhaps? She commissioned the text “A Walker in the City” from author Frederic Tuten. Frances formerly danced in the corps at the Kansas City Ballet before dedicating herself to her own practice which incorporates nineteenth-century pantomime, dance (including ballet), and painting. Her limber movements accompanied by a live violinist enlivened the evocative and poetic monologue. This summer Frances will be the first artist in residence to work at W.B. Yeats’s tower, where she will present work in honor of the centenary of his Nobel Prize win. It was beautiful to see Frances perform against the backdrop of Doring Baez work, two artists who—through different mediums—study and unearth art from the past recreating elements in their own form and language, both paying ode to artists and historical creative expression while shedding a contemporary lens on their work.

Claudia Doring Baez series The Americans will be on view in Wadström Tönnheim Gallery’s booth at VOLTA until the fair closes at 4PM on May 21st.

You Might Also Like

Peeling Back the Layers of Frida Kahlo as an Artist, Activist and Person at the Brooklyn Museum

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.