Khari Turner’s Dramatic Paintings Navigate Murky Waters

After a sojourn of painting in the same building as Karin Mamma Andersson, one of Sweden’s most famous artists, the American artist Khari Turner has made an impressive debut in Stockholm in a solo exhibition at CFHILL. To top this off, the artist traveled to Stockholm shortly after attending a showcase of his work in Venice during the biennale. For the 2021 Columbia MFA graduate, things are moving fast. A diptych in his show at CFHILL alludes to this acceleration in his career, depicting Icarus, who in Greek mythology overindulges by flying too close to the sun. Turner, an artist who is on the rise and aware of the risks that might pose, has turned to this thematic to ground his work.

Turner’s show, “As Below and Above,” presents figurative paintings from Turner’s residency in Stockholm alongside sculptures inspired by African masks. As a viewer, tensions between contradiction and fluidity and what might be taking place on the surface and what lies beneath come to light through the works. The exhibition is curated by Destinee Ross-Sutton, a dealer and gallerist who in the past couple of years has become known for championing young African-American and African artists. Notably, her sales contracts attempt to limit flipping, some including up to a 15% resale royalty for artists. Taking Turner under her wing to help further his career and market, she organized the showcase in Venice and included his work in an Artsy auction to benefit the Black AIDS Institute during this Pride month.

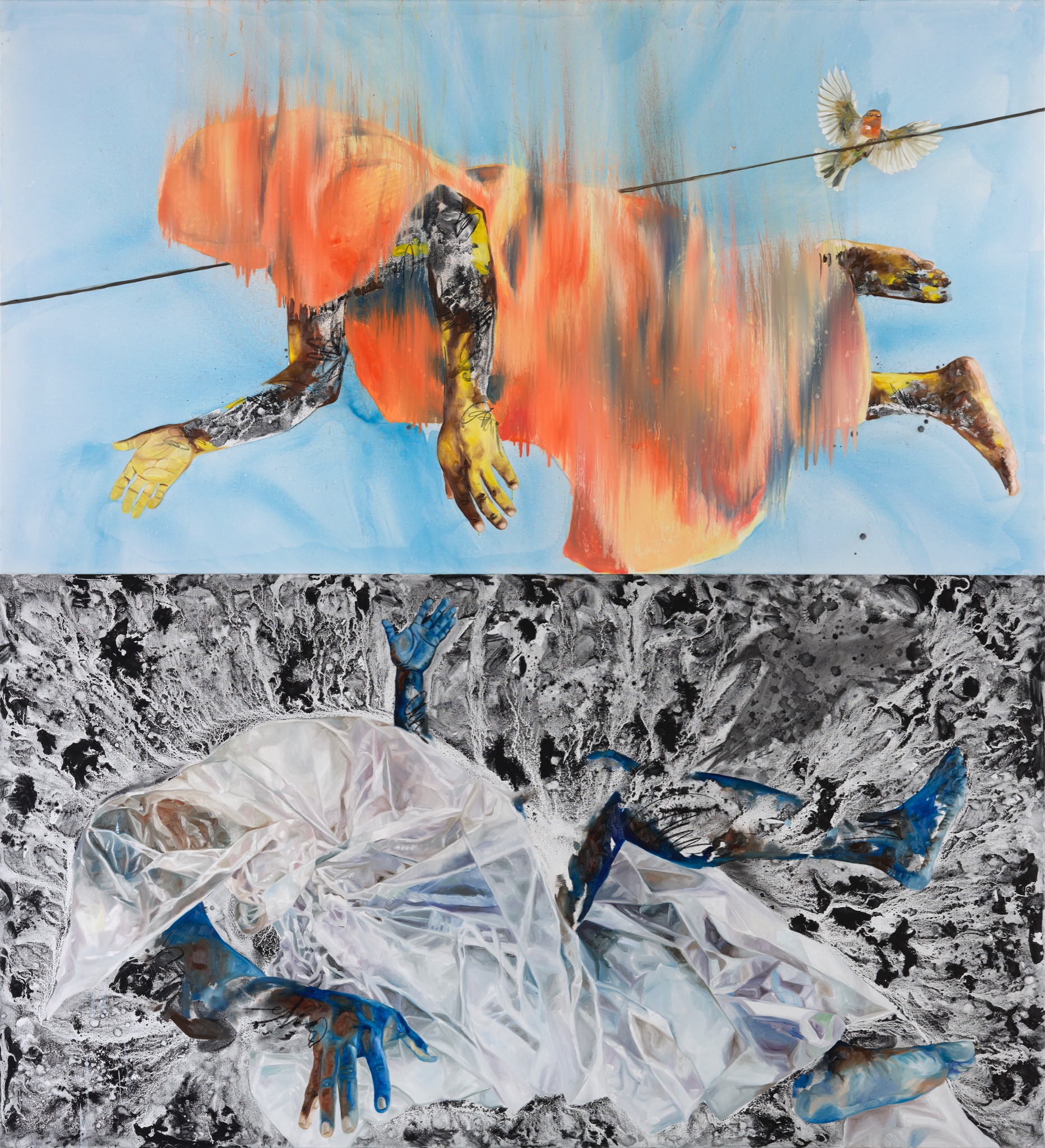

Icarus and the Sea Turtle is a centerpiece of the show, a diptych that is hung horizontally in the back of the exhibition space. The top canvas depicts a body clothed in an orange cloth floating in the sky with marks, tattoos perhaps, on its arms and a bird fervently in flight. The lower work’s color palette is subdued, composed of various hues of black, white, and gray. Its subject matter is palpably darker. The body is hardly there and a turtle eating plastic points to a symbiosis breakage—perhaps alluding to the risks posed by introducing elements that do not belong and reckless aspects of overzealous actions. This slight nod to our destruction of the environment in combination with the reference to Icarus places the artist and one of his fears in a central position: Will he undermine his own success?

The biblical reference, heaven and hell, is the most obvious link between “below” and “above.” If you have read the bible, you know that heaven and hell have no overlap. For the art history buff, it might feel more natural to look through the lens of the early Netherlandish artist Hieronymous Bosch’s triptych “Garden of Earthly Delights,” which depicts God and his creation of earth flanked by surreal heavenly and hellish imagery. In the Bosch triptych and the bible, these parts are all distinguished, chronological, and with a cause and effect determined by strict moral codes.

In contrast, Turner’s canvases are populated by muddled elements that are erased or blurred, alongside drips of paint streaks. He works in impasto with thick gobs of paint that he has formed using what looks like a knife. He doggedly collects water from different seas, oceans, and lakes which he incorporates in his work. “Unfortunately, he was not allowed to import water from Venice to the United States,” says the gallery attendant when I visit the show. “In Stockholm however, he collected water from many different places,” she continues.

Water is fluid: it overlaps, mixes, and is malleable. It is governed by energy. A drop of water has an exterior and interior. Interior molecules are attracted to all the molecules around them, while the exterior molecules are attracted to only the other surface molecules and to those below the surface thus creating surface tension. Water also interacts with other materials dependent on their composition. In his work, Turner explores these tensions by mixing water from different places with inks and other natural elements like sand.

Turner’s sculptures build a similar relationship with the natural world. For the exhibition, he has created masks turned inside out decorated with Kaori shells which he, in some cases, has installed with potted plants. Thus, the sculptures are alive and the exhibition must be watered, nurtured. These works are introspective, allowing visitors to both see and cultivate their own piece of African material culture and heritage.

CFHILL has together with selected curators carved out a space for Black figuration in Stockholm. In 2020, Ross-Sutton curated her first exhibition with the gallery, “Black Voices/Black Microcosms” featuring thirty Black contemporary artists including Rashaad Newsome, Mr. Star City, Amoako Boafo, and Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe. CFHILL has also worked with Addis Ababa and London-based gallery Addis Fine Art to show works by Tsedaye Makonnen, Helina Metaferia, Tariku Shiferaw and nine other artists from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Sudan, or their diaspora.

The paintings in “As Below and Above” engage with tensions pertaining to surface and subject matter. While the figures in the works are autobiographical, many do not resemble the artist. Some depict bodies in nature, where the body nearly merges with the vegetation. These works are flatter using brushstrokes rather than impasto that imbue a stillness. Further highlighting the different properties of his material, in some of the impasto works, Turner has allowed the sand to create a grainy effect within the more vivacious whirls of paint.

Bodies of water have many often overlapping functions: facilitators of global or local trade, places of leisure, reservoirs for water to sustain human, plant, and animal life, integral for agriculture, sites for environmental destruction, and homes for non-human organisms. I am curious to see how Turner will continue to develop ways to connect with his ambitious collection of water while engaging with a multitude of Black experiences.

You Might Also Like

Editors’ Picks: New York, St. Barthes

Kennedy Yanko Explores Shifting Identities Through Repurposed Metal

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.