“To Hang Is To Expose Yourself:” On the Road with Joan Bofill

The camera angle is sideways wrong, or maybe it’s perfect. Joan Bofill Amargós, the Spanish-born artist and director, Zoom frame captures half his face, tilted slightly upward so I can see the car’s sunroof, the Pennsylvania sky, and the rhythmic flash of powerlines slicing through the frame as he drives.

“Can you turn the camera a little more toward you?” I ask. He adjusts. “Yeah, like that. Keep the sunroof, but I want half your face.”

Through that rectangle of glass, clouds drift past. Trees. The occasional sun flash blaring across the frame like a jump cut. These serendipitous mini-movies playing above his head while we talk about portraits, about framing, about the act of looking at someone while your hands are busy capturing something else. Based in Barcelona, Bofill has exhibited internationally in Austin, Bulgaria, France, Lebanon, Miami, New York, Spain, and the UAE.

Behind him, just visible in the back of the car, paintings are stacked—muted passengers making their way from Miami to Manhattan for his October 16th opening at the Angel Orensanz Foundation curated by Carlo McCormick. I’m in my East Village apartment, but somehow the strange intimacy of these moving frames makes me feel like I’m riding shotgun.

“I’m in the middle of nowhere,” Bofill says. His face is handsome in that unshaven, cerebral, on-the-road way—dark eyes thoughtful, voice carrying the trace of Barcelona even after years of filming in Los Angeles, conducting interviews everywhere from West Hollywood rooftops to Belgrade apartments.

This isn’t just any road trip. It’s the final leg of a collecting journey that started in Miami, wound through Virginia, into Pennsylvania Amish country, and will culminate in a two-day exhibition called Double Portrait: Paintings In Conversation in collaboration with the Opening Gallery and art historian Sozita Goudouna. The paintings in the car are all by him, some belong to collectors who’ve loaned work back for the show, others are from his own archive.

Together they’ll hang alongside video devices at the Angel Orensanz Foundation, each portrait paired with footage of the conversation that generated it. David Lynch. David Cronenberg. Guillermo del Toro. Robert Williams. George Saunders. Chess grandmaster Garry Kasparov. Performance artist Johanna Went. Princess Elizabeth Karađorđević of Yugoslavia.

“When you see a painting you did, it takes you back to when you were doing it,” Bofill explains as sky blue floats above him. “The things you were having in your head at the time. They are kind of a time machine.” He has been making the “Double Portraits” since 2018 and explains that sometimes they end up in one of his films, and sometimes they are just a document to the encounter, for the Angel Orensanz show, the will be part of the “conversation loop” between painter, subject and viewer.

He tells me about a painting everyone wanted to buy at his first Miami exhibition. Everyone loved it. Everyone promised to purchase it. Nobody did. Years later, he thought it had been stolen from storage. Then it reappeared. The same day he picked it up, someone bought it. “I wasn’t even exhibiting it,” he says. “I was just holding it, telling the story, and the person said, ‘I would like to buy it.'”

The paintings know these stories. They’re witnesses.

Bofill’s double portrait practice emerged almost accidentally, the way the best artistic discoveries often do. He was making a documentary—and thought of himself as someone who positioned himself behind the camera, never in front of it. His first film explored Raymond Roussel, the pre-Surrealist French writer whose mechanical writing processes generated fantastical narratives. Through Roussel, Bofill discovered something crucial: “I had my own voice as a creator.”

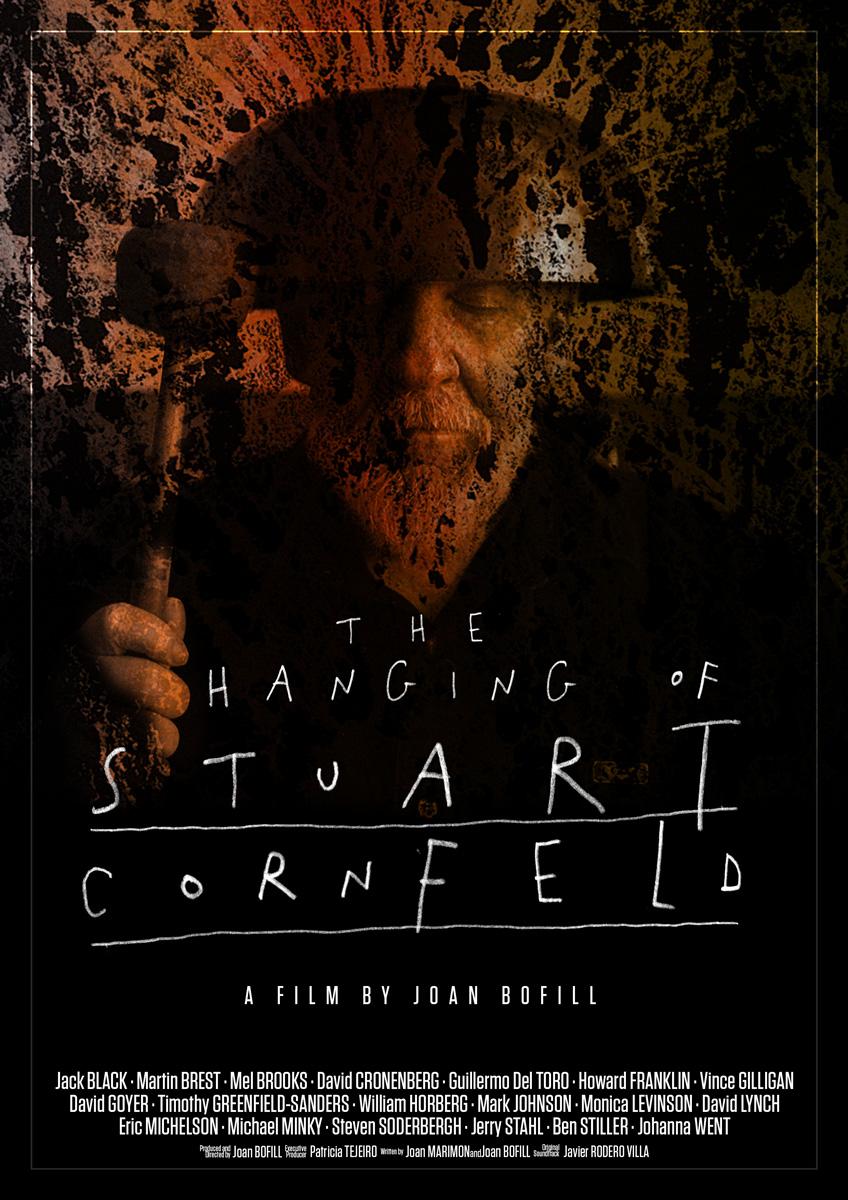

Then came Stuart Cornfeld.

They met through a chain of strange coincidences that led him to the 2015 Defcon hacking conference in Las Vegas and exchanges with performance artist and Survival Research Laboratories founder Mark Pauline, who made the next connection. Cornfeld was the iconoclastic producer behind, among others, The Elephant Man, The Fly, Zoolander—a man who navigated between avant-garde and mainstream with the kind of cultural fluency that made him the perfect collaborator for Joan’s next planned Roussel fiction film.

“He had this amazing knowledge about all kinds of references,” Bofill recalls. “Art, literature. Very wise. Very witty. And he loved surrealism.”

They bonded over Jean Cocteau’s Testament of Orpheus. They discussed Jung. Stuart offered book recommendations. Joan found himself drawing Stuart’s face in Barcelona, just for pleasure—something about the interesting angles, the character etched there. He’d add sentences Stuart had said to the drawings, sharing them casually.

Then Stuart got sick.

“He told me, ‘Joan, I can’t be involved in the film. I’m in a health situation that is not allowing me to be involved in any project.'” A pause. Through the sunroof, clouds fill the frame. “For me it was sad, because Stuart was the perfect person for this project.”

But in that same conversation, Bofill realized something else: every time he spent time with Stuart, it was fascinating. The stories about Mason Hoffenberg, the writer who wrote Candy with Terry Southern and who Stuart roomed with in his twenties. The encounters with William Burroughs. The web of artists and filmmakers and writers Stuart had known.

“I said, ‘Stuart, what about if I do a documentary on you?'”

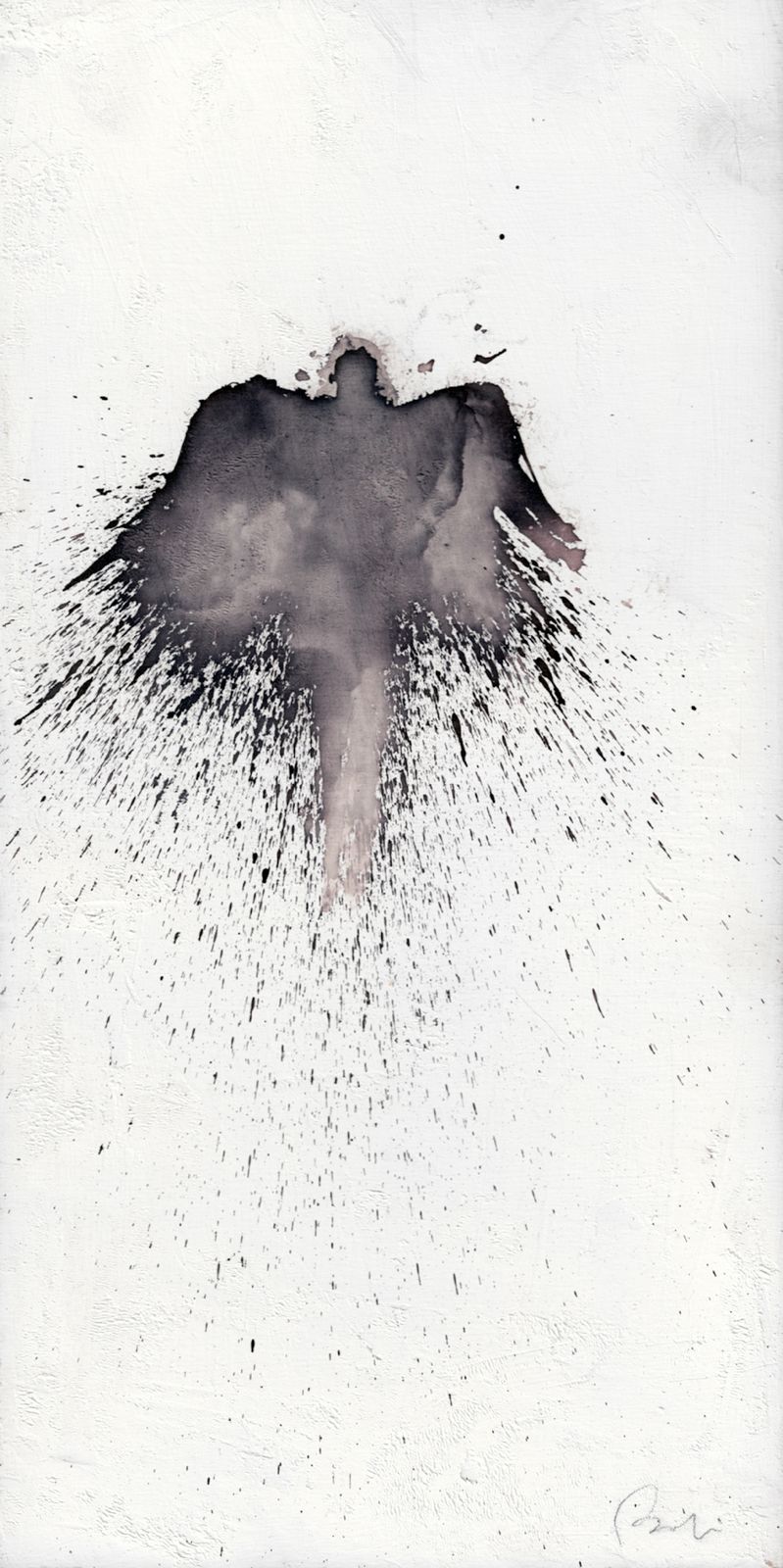

Double Portrait evolved from there. Bofill began sketching the people he interviewed for The Hanging of Stuart Cornfeld—quick portraits made in real-time, during the conversations themselves. Not polished studies. Not careful renderings. Just drafts made while listening, while talking, while divided attention created conditions for something unexpected.

“The less I think what I’m doing, the more interesting is the result,” Bofill says. “It’s not me that is doing this in a conscious way. I’m just putting myself in the conversation, or in the drawing. It’s a kind of strange dance.”

Robert Williams—the godfather of lowbrow art, founder of Juxtapoz—was one of those portraits. Bofill met him through Johanna Went, Stuart’s wife, who was friends with Williams. They bonded over Salvador Dalí, but it was one particular Williams painting that stuck with the artist: a woman leading a monster on a leash, except the monster had no teeth. The woman carried them in a basket.

“A monster without teeth,” Bofill says. “I found that really, really powerful.”

He lights up talking about Williams’s work—the comic book quality, the density of detail, how everything in a Williams painting exists for a reason. “You need to find out the details in the story. Really small details. Everything is connected.”

The same became true of Bofill’s process. The drawing captured one thing. The video another. Together they created what he calls “conversation loops”—where the filmed encounter, the physical portrait, and eventually the viewer’s experience layer into something that refuses to be just one medium.

The connection stutters. Bofill freezes mid-sentence, then returns. “Can you point it a little more toward you?” I ask. He adjusts again. Through the sunroof: more power lines, more trees, the whole American landscape scrolling past like a film strip.

There’s something perfect about directing the director while he’s literally in motion, carrying a cargo of portraits toward their hanging. We’re both framing, both looking, both trying to capture something that’s happening in real time.

Stuart died in 2020. It took Bofill five years to finish the film—fifty different cuts, working with editors, eventually locking himself away for six months to edit it alone. The breakthrough came when he understood what the title meant.

“The Hanging of Stuart Cornfeld,” Bofill says. “At first it was just a dark joke. But then I realized—to hang is to expose yourself. When you do a show, when you present your work, you’re open to be judged by the audience. This is being an artist. This is who I am.”

I ask if, in an alternative reality, the title of next week’s show could be The Hanging of Joan Bofill.

“Yes, absolutely,” he says without hesitation. “This is exactly what I learned from my adventure doing the film on Stuart. The process of exposing yourself.”

The car keeps moving toward Manhattan. The paintings shift slightly with the motion. In a week, those paintings behind him will be on the walls of that neo-Gothic synagogue on Norfolk Street, many paired with a screen showing the conversation that generated it—Lynch and Cronenberg and del Toro and Williams and all the others, talking while Bofill’s hand moved across paper, creating these strange double documents of encounter.

“It never ends,” Bofill had told me earlier, explaining the loop concept. “It’s one thing to the other. It puts me in a way that I want to open another drawer and then this drawer gives me another drawer. It’s all connected and infinite.”

Through the sunroof, the late afternoon light shifts. Another sun flash. Another stretch of power lines. Bofill drives on, carrying his cargo of conversations toward New York, toward exposure, toward the hanging.

Double Portrait: Paintings In Conversation runs October 16-17, 2025 at the Angel Orensanz Foundation, 172 Norfolk Street, New York. The Hanging of Stuart Cornfeld premieres at the American Film Institute Festival on October 23, 2025 at TCL Chinese Theater, Hollywood, Los Angeles.

You Might Also Like

‘Another Kind of Knowledge’: Portrait of Dorte Mandrup Explores Architecture Beyond Language

What's Your Reaction?

Mark Borden is a writer and photographer whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, Fast Company, Fortune, and The New York Times, where he was its first and only Creative-At-Large. His photography memoir Egospeed: Getaway Cars In The West Village will be published in 2026.