Using Processes of Embodiment Adebunmi Gbadebo Asserts Herself in Art and History

Marking the reopening of Claire Oliver’s Harlem gallery, amidst a moment of racial reckoning, “A Dilemma of Inheritance” presents work addressing slavery by Newark-based Nigerian-American artist Adebunmi Gbadebo. The exhibition recreates a reunion, a coming together of heritage, something that is overdue for many descendants of enslaved people. Passing down information from generation to generation and family archiving has not been available to many African-Americans because of American slavery, so many descendants are not fully aware of their lineage. Through abstract investigations of material, Gbadebo’s body of work takes us back to the lives of slaves and echoes their labor on two South Carolina plantations where the artist has traced back her roots.

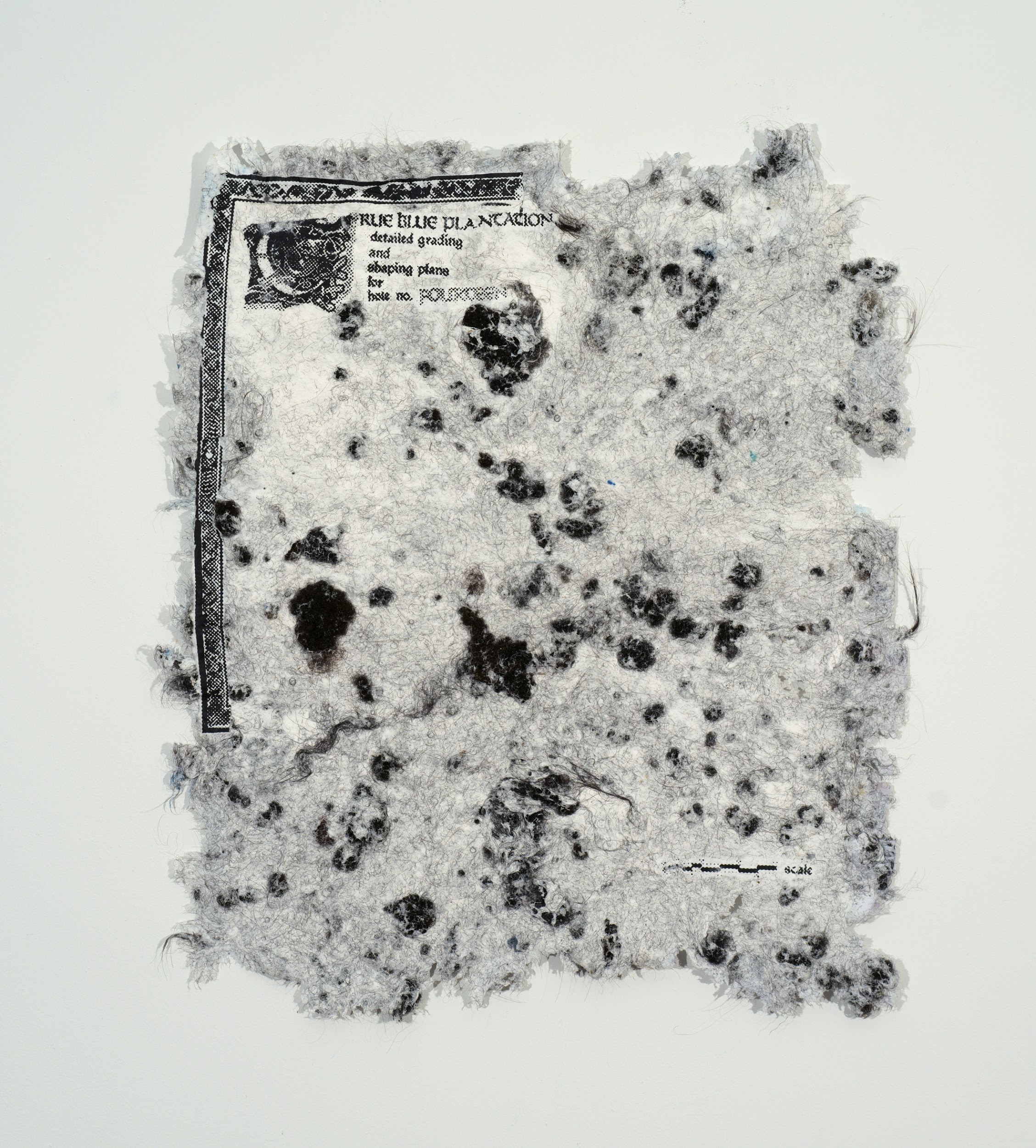

Both Carolina plantations were named True Blue. Beginning in 1947, after much experimentation, commercially grown Indigo, a blue dye, became the second most valuable export, after rice, in the region. ‘Field slaves’ planted, weeded, and harvested while ‘Indigo slaves,’ who were deemed more valuable, converted the plant to dye. The pieces in “A Dilemma of Inheritance” are presented in two sections. The first half of the show uses the architectural planning of the plantation as a foundation. The second, more emotive and affective, integrates names of formerly enslaved people who worked on the plantation. As a means to embody the laboring bodies and highlight the economic contribution of her enslaved ancestors, Gbadebo has crafted her work from rice paper, cotton, indigo dye, and human hair – all integral to the prosperity of plantation owners.

Hair sourced from black people is a central material and serves as an index to represent Black origin, but also future. The layered cultural importance of black hair unravels throughout the various pieces, a universal starting point is a simple fact that hair stores heritage and DNA. By placing hair on top of the plantation’s architectural plan, an authoritarian concept, Gbadebo asserts herself in space..

Originally from Maplewood, New Jersey, she is able to trace back her roots to a specific plantation, something that many African-Americans are not able to pinpoint. Gbadebo gives a stage to the untold stories that did not have the same platform. The experience that is embedded in each piece is raw, simply the emotional turbulence was nothing more than normal for a person condemned to servitude and triggering questions about our own lineage and emotions. And, how the western canon of art has often overlooked blackness in America, and the aftermath of colonization.

Gbadebo claims her heritage, her own narrative while questioning how heritage shapes our personal narratives. Exploration of our own culture is an intimate and emotional experience that opens closed wounds. The Black hair, the rice paper, the vibrant shades of blue, and the cotton all echo the day-to-day labor of enslaved people. By confronting these goods people of African descent, and others may come to grasp the magnitude of the economic contributions that slaves brought to their slave owners. The juxtaposition of these items paired with newer goods such as commercial denim and loc’ed hair reminds us of the lasting impact and residues of slave labor. By integrating not only the hair but the products produced by disenfranchised individuals Gbadebo addresses the whole system of slavery from producer to product in the forty-two works on view.

Reparations lurk throughout the showcase. ”We recognize our lineage as a generational trust, as inheritance, and the real dilemma posed by reparations is just that: a dilemma of inheritance,” the journalist and author ta-Nehisi Coastes said at a House Judiciary hearing in June 2019, he continued, “it is impossible to imagine America without the inheritance of slavery.” It is impossible to imagine America without the inheritance of slavery. The imagery of America is embedded within slavery and separating those concepts seems inconceivable – yet it is time to follow or lead to find words, actions, and policy to untangle and rectify these concepts. Following 250 years of slavery, 60 years of Jim Crow laws, and the past 35 years of exclusive and racist housing policies, Coastes used this testimony as a means to say that African-Americans have continuously been exploited by the American government and that reparations are a way for the American government to make amends.

The framework of “A Dilemma of Inheritance,” like the United States of America, is a complex, uncomfortable, and raw moment, built from momentum how we got to this current state in society. “18th Hole” uses a traditional method of papermaking, cotton, and black hair serve as the foundation of the piece. The paper document of the former names of slaves is imposed on this material as if breaking free from the materials that occupied them on the plantation. The distinct blue echoes the name of the plantation, while the white from the cotton echoes the manual labor of plantation production.

Black hair is central throughout this show and is significant for Gbadebo’s practice. During her undergraduate education at the School of Visual Arts she was the only person of African-American descent in the graduating class. Her first interaction with blackness in art was when she saw the portrait of Olympia by Edward Manet in a class. The controversial aspect of a black woman in an artwork paired with the lack of time spent on her made it apparent that the lack of visual representation of Africans, even when we are a subject in art, are still not focused on. What Gbadebo has realized that with these factors in place, especially in painting it will always be examined as a white-centric canon of art history. This understanding made her realize she did not want to use the eurocentric history’s material so her work can take a context of its own. This is evident in her use of materials that link directly back to American slavery. The power of hair, especially African-American hair is consistently overlooked by western European images. The context of our hair having the ability to connect us back to the continent of African is an important factor for Gbadebo.

Through the works on view, viewers are forced to look at what they have and where it came from. We live in a world where our rights, what we do on a day to day basis are a direct result of slavery; our placement in life is not an accident, but an effect.

The way each material comes together is therapeutic for the artist. She is confronting the use of the materials during slavery by recreating their purpose, while also creating her own narrative. The abstractions of the work allow for the era of slavery not to consume them fully. Gbadebo reclaims the land her ancestors were suppressed to by rendering the map in a new light where the black experience is represented. Through Gbadebo placing the materials in the ways she deems fit, she rebels against directions her ancestors had to abide by.

Cotton, rice, and indigo are so deeply embedded into our society that their harsh and racialized history of procurement through slavery and slave trade have been forgotten; Gbadebo’s work is a reminder that their production is entrenched in violence and colonization. To confront the future we have to challenge the past, and that is evident through the emotional responses to “A Dilemma of Inheritance.” The layered fashion we can see that Gbadebo uses in her works creates a map, a path for exploration as it pertains to the slave trade and the generations that were born from it.

You will leave “A Dilemma of Inheritance” truly questioning if the America we know and the way we live our lives in relative comfort, would be possible without the uncomfortable and sometimes forgotten history of slavery.

The exhibition is on view at Claire Oliver, 2288 Adam Clayton Powell Jr Blvd, New York, NY 10030, Harlem.

You Might Also Like

The Women’s March on Washington and it’s Racial Divide

Quilted Portraits that Evoke the Racialized and Gendered History of Craft

What's Your Reaction?

An art professional with Chicago-based art non-profit Project&, Caira Moreira-Brown studied Art History at The Ohio State University receiving a B.A in History of Art with an emphasis on Post-Modern and African-American art history. She regularly writes for FAD Magazine and founded the podcast The Curatorial Blonde. Previously, she has held positions in gallery administration at Fredrich Petzel Gallery, 67 Gallery, Joseph editions and has worked at Kim Heirston Art Advisory and The Wexner Center for The Arts. Moreira-Brown is interested in post-modern race relations and narrative change. l igram l email l