Coerced Consent: Alx Velozo’s ‘Sick Play’ Challenges Medical Power

On a Sunday in December, the trans and disabled sculptor, performance artist, and educator Alx Velozo welcomed me into Sleepwalker Collective’s art gallery in downtown Baltimore to see their solo Sick Play. In the unassuming rowhouse, a world exploring the power dynamics of chronic illness and disability and its effects on sensation unfolded. As the exhibition narrates, pain, domination, and submission are present in BDSM communities and the medical sphere alike, but approached very differently. “Interfacing with the medical industrial complex in such a constant and long-term way has informed the ways I am always negotiating power. It has put me inside of coerced consent in which consent is either completely absent or hinged on meeting my survival needs in late-stage capitalism,” Velozo told me.

To Velozo the ‘patient’ is a heteronomous construction—one that affects the way in which power and autonomy are exercised by the patient and medical practitioner in the medicalized setting. It’s not so different, Velozo pointed out, from trans U.S. Americans who are facing attacks on their right to gender affirming care, restrooms, and sports and rampant violent transphobia. Historically, trans and queer people have also been classified as ‘sick,’ a term used colloquially to refer to “perversion.” It was not until 1973 that the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. It would take fourteen more years for the removal to take full effect, and people and institutions continue to pathologize queer and trans people, claiming that they are mentally ill.

Trans and queerness is an important dimension of the work, especially its relationship to what Velozo refers to as “communities of sensation,” the healthcare setting, queer communities, and BDSM subcultures, as prosthetic, proxy, or abstraction. They explain: “I am fascinated with how illness complicates and breaks binaries when interpreting what I am sensing. Whether it is pleasure versus pain or a dangerous versus benign, most of these categories become porous in the context of disabling sickness.”

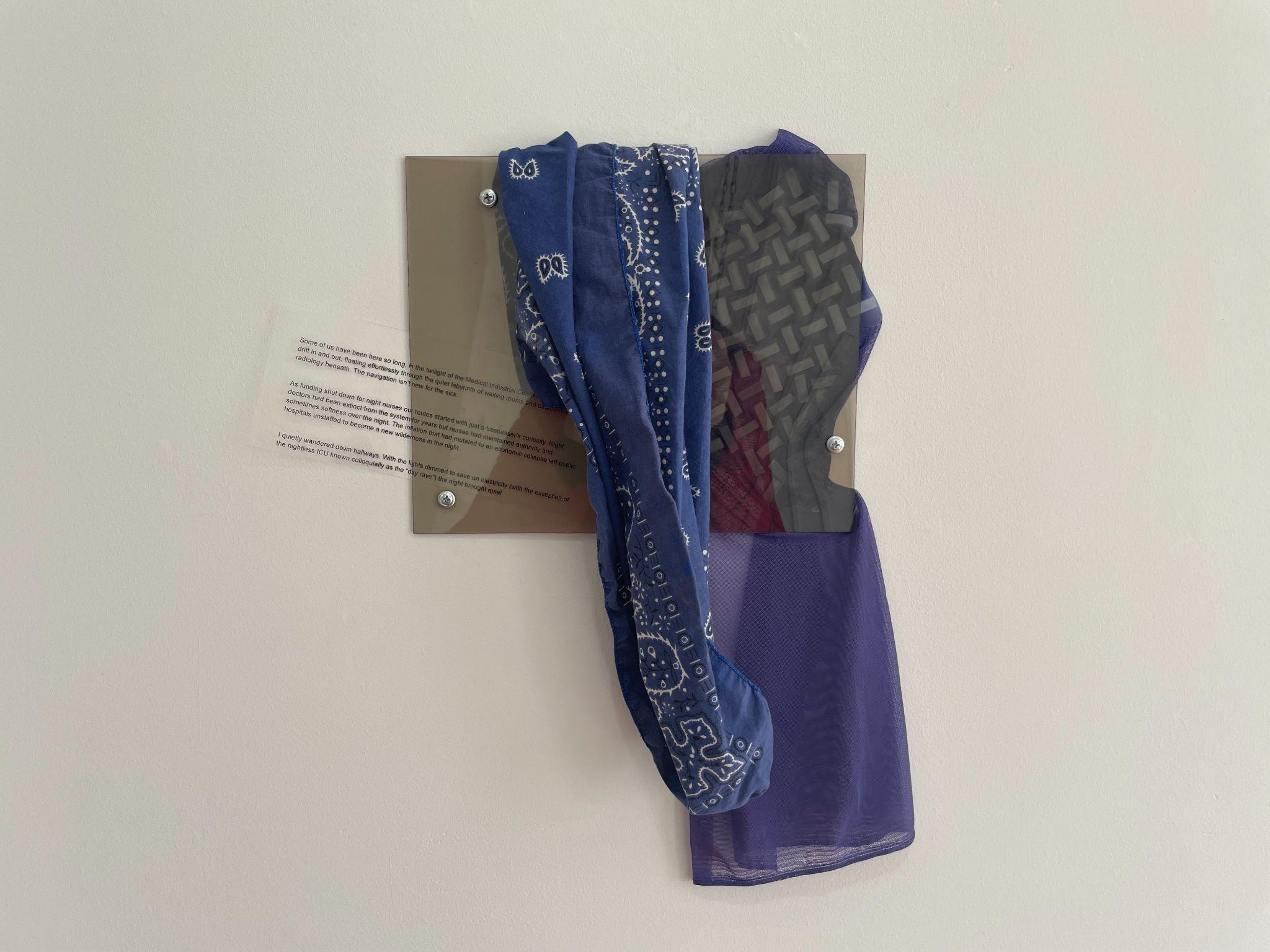

Centering the exhibition is the interplay between the BDSM Hanky Code with a standardized hospital color-coded system used within medical care. Kink communities use the Hanky Code, colored handkerchiefs (hankies), worn partially visible in their back pockets to communicate sexual interest—a system of autonomous and consensual sensorial solidification. In five collages and color studies hung around the galleries, Velozo overlaps medical materials—all their own collected from hospital visits—with colored plexiglass panels matching typical categorization systems in hospital settings, hankies, and small text vignettes in which they explore their experiences. By placing these two systems side by side, the artist points to how the BDSM community creates autonomy for all while the industrial medical complex removes it from their patients creating a thoughtful commentary on consent.

As the colored plexiglass, hankies, and socks overlap, each of their colors change as they are affected by the discourse of the others—as discussions of consent and autonomy within BDSM culture invite reflections on the ways in which the disabled body, the sick body, is objectified, disenfranchised, and controlled, and the ways in which BDSM cultures (not the ones that fetishize disability) provide discourse to challenge the ableism at the heart of many disabled people’s lived experience within the health care system. The presentation is light-hearted in its execution, but the topic is heavy: “I’ve always been invested in play … and one of the frameworks where adults really understand and recognize play is through kink. Using the legible referents and materials of BDSM invites a familiar play and interpretation of that play,” Velozo said.

In Sick Play Velozo’s writing, which they call ‘sick flagging fantasies,’ forms a foundation for the work. Some are fictional sick scene fantasies featuring disabled and ill actors, but many are their own experiences. There was an intense vulnerability, Velozo admitted, in putting their experiences and sick imaginings out there. The exhibition points out that in medicalized settings, disabled people are constantly exposed, affecting the power dynamics between recipient and giver of treatment, diagnoses, and within the U.S. healthcare system, requiring them to navigate validity, insurance coverage, and disability benefits. It is these uneven power dynamics that reduce the disabled body, the sick body, to a commodity. These uneven power dynamics are at the heart of ableist policies in the United States that continue to forcibly institutionalize, sterilize, and impoverish disabled people.

Partially because access is a language they speak and navigate as an educator, accessibility professional, and chronically ill artist, Velozo has made accessibility features part of the work and design of the space through tactile boards, QR codes to screen reader accessible text, and visual descriptions. Accessibility is not an afterthought. Instead of a written description being a translation of visual content into text, an art with one degree of separation from the original, Velozo argues that it is another language through which they communicate, and in the spirit of the exhibition, another sensory touch point through which the colors, textures, and shapes come into being in the gallery.

For instance, if you read my visual description of the work pictured above, consider how it increases your textural understanding of the piece or its colors, and how guides you to consider certain details. Mounted on a white wall, a square piece of gray translucent plexiglass is drilled slightly askew, trapping several overlapping materials that spill beyond its edges: a paragraph of printed text on clear acetate, a navy blue bandana that drapes and hangs over the plexi, and a piece of dark blue mesh with a visible rubber anti-slip pattern. Visual descriptors or alt texts, as they sometimes are called, encourage deeper reading.

Fellow disabled artist-curator Panteha Abareshi noted in a recent interview that the translation of visual content into written or spoken description is itself an act of disruption and cultural construction—artists must be fully part of the process to ensure the integrity of their work in every way it’s encountered by the viewer. Velozo concurred, “illness forever changes one’s relationship to sensation, and I think about how to translate sensation into visual works. Even though visitors are invited to touch all of my work, I’m also interested in how many people will only experience this work through a description or from afar or an image,” they said.

Whether it’s using the same body-safe silicone used for prosthetics and packers or incorporating their own medical material cultures into the exhibition, all of the surgery bonnets and grippy socks are their own; every object on display carries a historical weight and power to it. Velozo’s Sick Play is a timely reflection on how art that explores disabled and chronically ill lived experience is not only a language of accessibility but an invitation for all people to explore how consent, autonomy, and sensation is codified and understood in their bodies.

Sick Play is on view through January 21, 2026 at Sleepwalker Collective Gallery, 324 East 23rd Street, Baltimore, MD 21218. Schedule an appointment by emailing sleepwalkercollective@gmail.com.

You Might Also Like

What's Your Reaction?

Emma Cieslik (she/her) is a queer, disabled, and neurodivergent museum professional and writer based in Washington, DC. She is also a religious scholar interested in the intersections of religion, gender, sexuality, and material culture, especially focused on queer religious identity and accessible histories.