Processes of Seduction. Zoe Walsh Talks About Their Show “Remote Light” at Zeit Contemporary Art

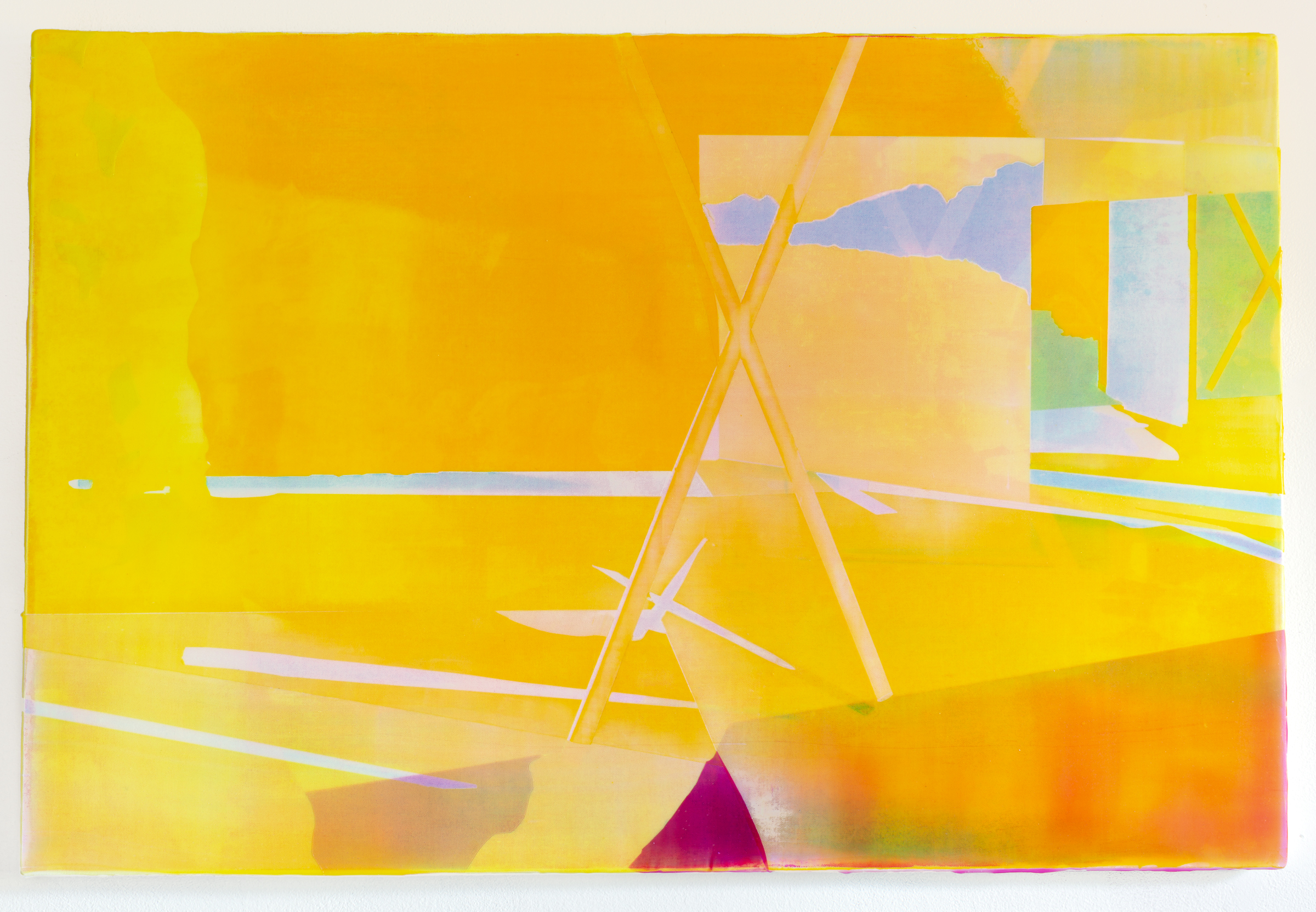

Los Angeles is often looked down upon for its superficiality. But, the artist Zoe Walsh sees the city’s signature trait as favorable. After graduating with an MFA from Yale University, Walsh returned to LA, where they had pursued their undergraduate degree some years earlier. For them, this superficiality translates into an inherent relationship to the unnatural that provides a solid foundation from which to explore gender and sexuality. With a labor-intensive artistic process and as an attempt to create trans subjectivity, Walsh transforms film stills and photographs to abstract painting. Preoccupied by LA’s unique light and gender performances, their most recent series of acrylic paintings are based on film stills from “Ramcharger,” a 1984 gay male pornographic film set in the desert. Curated by Bianca Boragi, a fellow Yalie, a selection of works from this series are currently view in an online exhibition at Zeit Contemporary Art.

If the great achievement of Gerhard Richter was to rethink painting in the age of photography, the great accomplishment of Zoe Walsh is to reinvigorate painting in the age of Photoshop [and] Instagram.

– Joan Robledo-Palop, Zeit Contemporary Art

Founded in 2016, Zeit Contemporary Art is pushing the boundaries of online exhibitions through an eclectic selection of limited-run-time online shows. The gallery has previously shown Eddie Aparicio, Julia Rooney, and Bryson Rand. Zeit Contemporary Art’s next online exhibition will feature the work of queer artist and activist Vincent Tiley and is slated to go live in the spring. In addition to its online presence, Zeit Contemporary Art has warehouses with showrooms in New York and Switzerland. The gallery shows emerging artists but also specializes in secondary market work. In January 2019, it will present “Minimal Means: Concrete Inventions in the US, Brazil and Spain,” a historically focused show, in a temporary exhibition space on the Upper East Side.

It is the first time that Walsh shows with Zeit Contemporary Art. “If the great achievement of Gerhard Richter was to rethink painting in the age of photography, the great accomplishment of Zoe Walsh is to reinvigorate painting in the age of Photoshop, Instagram and other electronic devices that mediate our relationship with images,” says art historian and gallerist Joan Robledo-Palop about the artists work.

Above: Zoe Walsh in their studio. Previous: All photographs of artwork courtesy of Zeit Contemporary Art.

Above: Zoe Walsh in their studio. Previous: All photographs of artwork courtesy of Zeit Contemporary Art.

In conjunction with the online exhibition “Remote Light” featuring Walsh’s most recent work, Cultbytes took the time to interview the artist about their artistic drive and the works in the show.

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand: I love the CMY-palette hues and cinematic references in your works. How does your painting practice interact with photography and the digital sphere?

Zoe Walsh: Thank you so much! I appreciate that observation because the address to photographic and digital visuality is an important facet of my practice. I spend a lot of time working digitally leading up to each new series of paintings. This involves subjecting photographic quotations to material transformations – converting a pixelated silhouette to a vector shape, importing it to a digital modelling program (SketchUp), and rendering a digital picture of a virtual space that contains that shape. Following that, I recombine these renderings into digital montages on Photoshop. These montages act as plans for the paintings.

Intense. How does this translate into painting?

Whether I am using an intermediary matrix (four paintings in “Remote Light” include screen printed layers) or not, there will inevitably be glitches that occur in the movement from the digital to paint. The moments when the physical behavior of the paint exceeds measurement and reproducibility — the kind of trace produced by a wavering hand or varying viscosity of a gel — are vital to the work. Color is another point of departure as the color mixing in the subtractive spectrum only approximates the color of the digital screen. As you point out, the paintings are made with translucent glazes of cyan, magenta, and yellow on bright white gesso which reflects light. This operation prompts me to consider the eye of a viewer as a site of exposure.

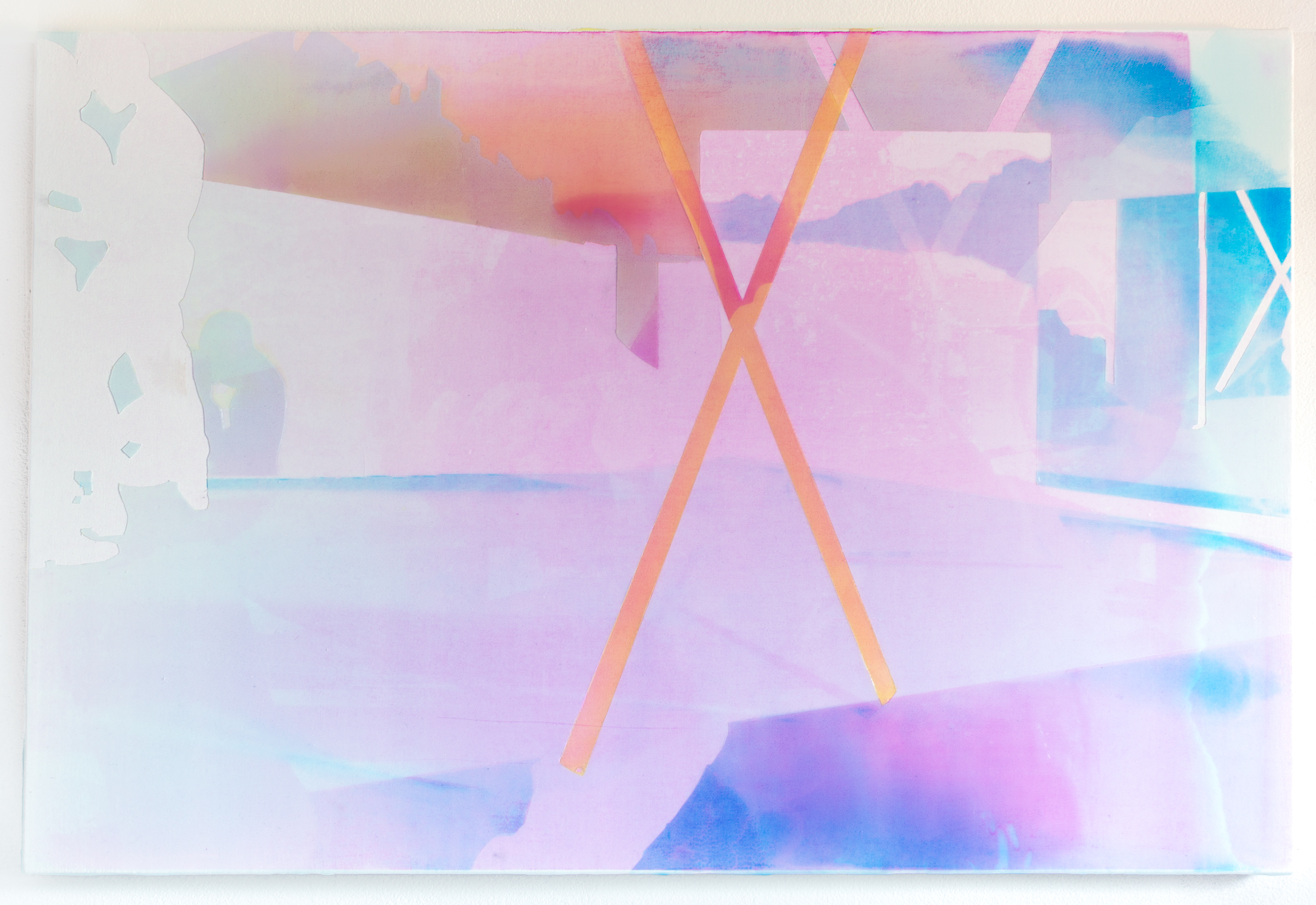

Zoe Walsh, loop, pull, bleed, 2018. Acrylic on canvas.

Zoe Walsh, loop, pull, bleed, 2018. Acrylic on canvas.

Explorations of masculinity have been part of your practice for quite some time. Where does this interest stem from and what do you hope to contribute to the current discussion on gender?

I first started going to archives looking for visual records of trans-masculine subjects that I could project my own identification onto. I encountered misalignment and absence. As many artists and historians have illuminated, the archive is an ordering system that reflects structures of authority and power. Catherine Lord articulates this succinctly in “Their Memory is Playing Tricks on Her: Notes toward a Calligraphy of Rage” in which she writes, “[t]he archive is a pledge to the future. So said Jacques Derrida. Heterosexuality is about reproduction. Same thing. History belongs to the victors.”[1] I wondered if I could make work that constructs trans subjectivity without making it visible through the same representational structures that the archive recognizes. In this exploration, I became interested in photographs that seem to contain an excess of desire on the part of the author, such as those by Wilhelm von Gloeden.

Cool. Right, in 2016, you worked on “Projections with Wilhelm von Gloeden” named after the German photographer known for pastoral studies of Sicilian boys.

Yes. As I spent time working with these appropriated images, it became clear that I needed to consider the relationship of painting to photography at a more material level. I owe this realization to a class I took with Carol Armstrong at Yale, which investigated the histories and discourses of medium specificity. It enabled me to have a more nuanced understanding of the ways that gender and sexuality have always been embedded in the discursive establishment of boundaries between mediums. The work that I am making now seeks to develop a hybrid entanglement across time through eroto-intermediality.

Who else has inspired your work?

I’m drawn to the work that David Getsy is doing on gender, sexuality, and abstraction. I believe it is relevant to how I consider the possibilities for what I could contribute to the current discourse on gender in that I aspire to address trans identity through formal and material relationships. I frequently think of Djuna Barnes’ modernist novel Nightwood and its complicated address to vision through text as a model for a type of queer formalism that I would eagerly construct.

Why Ramcharger (1984)?

My relationship to archival research often feels fragmentary and having to do more with serendipitous encounter than with skillful navigation of a database. The still photographs from the Ramcharger set are these beautiful achromatic prints held at the ONE Archives in Los Angeles. The lushly rendered value scale feels like the container for heat that is absent from the color space, yet signified through the content. The photographs are taken in a desert landscape and there is a strikingly hyperbolic contrast between the figures and the open horizon. The images construct an erotic fantasy of semi-public sex alongside an open road. I am attracted to the pictures as I am aware of the multiple registers of erasure and compromise that my visual pleasure is entangled with. I think of Jose Muñoz’s work on disidentification as a model for how to comprehend and engage with these paradoxical relationships.

I also appreciate the capacity for the pornographic to trouble the boundaries between touch and sight and the corresponding Cartesian split between body and mind.

– Zoe Walsh

When people look at this series and haven’t yet figured out that it’s based on pornography, do you tell them?

I do. I am fascinated by the paradoxes of spectatorship and embodiment that are evoked through engagement with pornographic material. Furthermore, pornography features significantly in the history of painting and photography. Early discourses on painting describe painting itself as an act of seduction. I also appreciate the capacity for the pornographic to trouble the boundaries between touch and sight and the corresponding Cartesian split between body and mind.

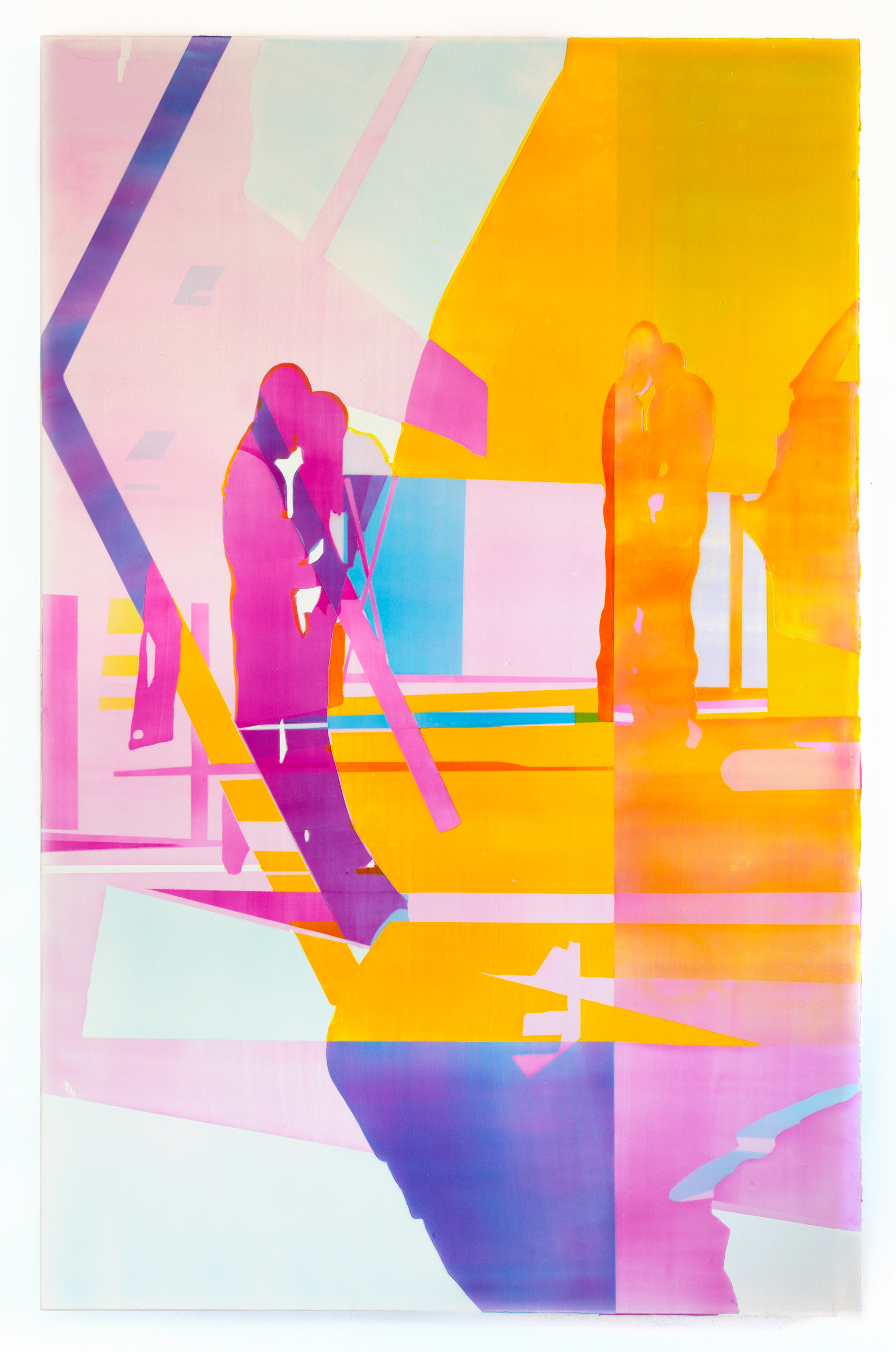

Zoe Walsh, opening (flood), 2018. Acrylic on canvas.

Zoe Walsh, opening (flood), 2018. Acrylic on canvas.

How does being in LA inform your work?

There is a such a unique character to the light in Los Angeles, which I know both through my direct experience of it and through its abundant mediated reproductions. There’s a longstanding perception of LA as being surface-oriented, lacking depth. I love living in this space and considering these biases from within. I feel some sort of trans affinity with Los Angeles in the way that an unmediated relationship to the “natural” is already foreclosed.

Being an online exhibition “Remote Light” is really pushing the envelope to formalize the art viewing experience in the digital sphere. How did you feel when you were approaching for this show?

To be honest, I feel some trepidation about that trajectory. But, my work acts on this loop with the digital and the virtual, so it seems fitting to see this series online. I like that this show links this body of work together, making the paintings visible simultaneously. I was also eager for an opportunity to work with Bianca Boragi, who curated the show and has been a wonderful source of support.

What can be done for the viewing experience online to improve?

I think that is an interesting question. It seems like there are a lot of different possibility models for virtual spectatorship. I had an opportunity to contribute to another project that has a digital life with Virtual Dream Center, an artist-run platform. To access the exhibitions, a spectator downloads the application to then navigate the space like a video game. A different set of questions emerge with this more immersive space. There is still the persistence of the screen acting as a window and I’m curious about projects that seek to reconfigure the fundamental paradigms of a spectator’s relationship to screen space.

What are you currently working on?

I’m currently building on the formal processes that I employed for Remote Light in a series of paintings stemming from scenes by a swimming pool. I’m curious about the pool as a threshold space of heightened surveillance, exclusion, unfixed boundaries between public and private, and, potentially, pleasure. Ironically, or maybe fittingly, I’ve always felt a great discomfort at swimming pools. I hope to mine some of this personal experience as I investigate the architectural, social, and visual history of the pool in Los Angeles.

“Remote Light” is accessible through Zeit Contemporary Art’s Artsy page through December 28th, 2018.

___

[1] Catherine Lord, “Their Memory is Playing Tricks on Her: Notes toward a Calligraphy of Rage,” in Queer: Documents of Contemporary Art, ed David Getsy (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2016), 101.

What's Your Reaction?

Anna Mikaela Ekstrand is editor-in-chief and founder of Cultbytes. She mediates art through writing, curating, and lecturing. Her latest books are Assuming Asymmetries: Conversations on Curating Public Art Projects of the 1980s and 1990s and Curating Beyond the Mainstream. Send your inquiries, tips, and pitches to info@cultbytes.com.