Kerry James Marshall Takes on Art History at MOCA Los Angeles

Fresh off of its debut at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and then the Met Breuer, “Kerry James Marshall: Mastry” has graced Los Angeles with a much-needed, thought-provoking exhibition. In the midst of the hyped-up biennial-esque experiences like Desert-X and The 14th Factory, as well as shows that resemble amusement parks more than art exhibitions—looking at you Museum of Ice Cream—Marshall’s 35-year retrospective at LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art presents a refreshing step back into the walls of the cultural institution. While the merit of these interdisciplinary, interactive experiences is undeniable and necessary to steer the art world away from stagnation, there is something to be said about the value of a solid, intellectual exhibition.

Curated by MOCA’s Helen Molesworth, along with Ian Alteveer (Met Breuer) and Dieter Roelstraete (MCA Chicago), the show explores the long career of Kerry James Marshall, and is the artist’s first major retrospective in the United States. With nearly 80 works, the exhibition unfolds chronologically and showcases Marshall’s deep commitment to challenging the narrative of art history in order to point out the imbalances within the white, male-dominated field. Based in Chicago since the late 1980s, Marshall also has strong roots in LA that helped guide his artistic practice. He explains, “You can’t be born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955 and grow up in South Central near the Black Panthers headquarters, and not feel like you’ve got some kind of social responsibility. You can’t move to Watts in 1963 and not speak about it.”

“You can’t be born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955 and grow up in South Central near the Black Panthers headquarters, and not feel like you’ve got some kind of social responsibility. You can’t move to Watts in 1963 and not speak about it.” – Kerry James Marshall.

He began his art practice with a consciousness of the absence of black artists from museums and from art history. He took an academic approach to understanding what artworks end up in museums and what images resonate through time. As if creating a formula for good art, specifically good painting, Marshall sought to replace the preexisting, privileged variables with his own to fill in the gaps. The point for him is not to reinvent art or introduce some new form, but rather to focus on the over 600 years of history of art and solidify the position of the black artist within that history. As Marshall puts it, “There’s a difference between making paintings and changing the idea of what paintings are supposed to look like.”

This academic, scientific approach to art-making relates to the title of the show, “Mastry.” The idea of mastery suggests that once you have perfected something and become a master, you are free to make decisions because you have perfected that thing. The subject mastered becomes second nature and the master, having reached the limitations of the existing material, is able to push these boundaries and expand the subject to a higher level.

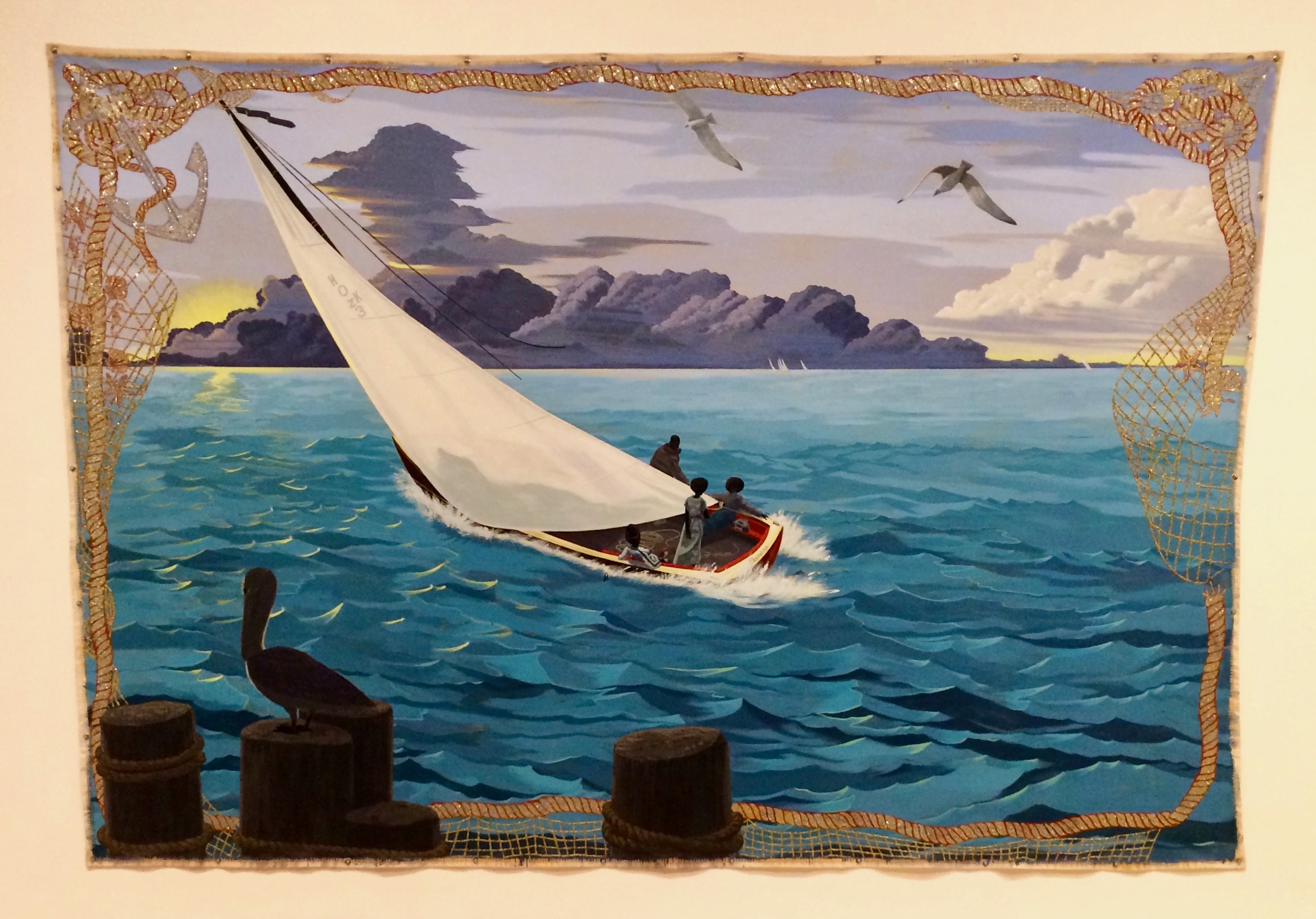

Previous:Installation view: “Kerry James Marshall: Mastry.” Image courtesy of MOCA Los Angeles. Above: Kerry James Marshall. “Gulf Stream,” 2003. Acrylic and glitter on canvas. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Photo: Annabel Keenan.

In his works, Marshall paints black figures in everyday settings and engaging in everyday activities in order to normalize seeing black figures in painting. His works are straightforward and devoid of overly-intellectualized content. They are large, even monumental in scale. In “Gulf Stream,” Marshall depicts four figures riding a boat through beautiful ripples of water that reflect the setting sun. Two of the figures sit relaxing while the other two stand, possibly to direct the boat. Marshall has painted a silver anchor and a gold rope with nets in acrylic and glitter that frame the whole scene. A bird sits on a wooden post outside the rope, as if a spectator to the scene. The dark afros of the figures and their muted clothing contrast the pristine white sail and the bright blue water. The canvas is unstretched, as are many of Marshall’s works, which the artist explains is so the pieces are easier to roll up and transport.

Kerry James Marshall. “Voyager,” 1992. Acrylic and collage on canvas. National Gallery of Art, D.C. Photo: Annabel Keenan.

A much earlier work of a similar subject is “Voyager,” from 1992. Also unstretched, the piece depicts two figures on a small green boat called Wanderer. Made over 10 years before “Gulf Stream,” the work shows Marshall’s much rougher treatment of the paint with fewer clean lines, thinner application, and more drips. “Voyager” also includes some collage elements that add texture to an overall flat surface. The name of the ship refers to the retrofitted yacht that violated the Slave Importation Act of 1807 and brought 409 enslaved West Africans to Jekyll Island, Georgia in 1858. As is often the case with Marshall’s works, the piece includes a variety of symbols that suggest different cultures. In this piece, the vévé crosses of Haitian voodoo tradition mix with Nigerian nsibidi icons and the number seven, which represents the seven Yoruban deities.

Kerry James Marshall. “Vignette,” 2003. Acrylic on fiberglass. Defares Collection. Photo: Annabel Keenan.

For Marshall, art is a way to produce knowledge and point things out to the viewer. His works simply bring light to issues and themes that he thinks the viewer might not notice, or that he simply wants to talk about. He’s not directing any sort of discussion or inciting any debate, but rather giving a form to things that might go overlooked. He makes the viewer pause and reflect on the subject he presents. In this line, there is no suggestion of self-expression. Rather, Marshall himself describes his approach to making art as an intellectual activity.

Kerry James Marshall. “Untitled (Painter),” 2009. Acrylic on PVC panel. Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Image courtesy of MCA Chicago.

As part of this intellectual activity, Marshall analyses the history of art and uses preexisting images and tropes to create his own works. In this sense, he fits in nicely within the genre of Pictures Generation artists with whom he is sometimes associated. While this connection may not seem obvious, Marshall was indeed born into a world fully immersed in mass media and television as were artists including Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, Jenny Holzer, and Jeff Koons. In conversation with Helen Molesworth, Marshall agreed that he is technically part of this group, but he noted that the seductive qualities of television as it existed when he was growing up were very different from those of today’s world. Televisions of his childhood had only a few channels and when they were turned off, the viewer checked out and left the shows behind. Marshall sets himself apart from his contemporary Pictures Generation artists in that the images that inform his works are vague references and layers of memories as opposed to direct representations or remakings of preexisting images.

Cindy Sherman. “Untitled #216,” 1989. Chromogenic color print. The Broad Museum. Image courtesy of the Broad Museum.

Marshall’s connection to the Pictures Generation is not obvious at first, but he is similar to one artist in particular, Cindy Sherman. In her so-called History Portrait series, Sherman recreates Old Master paintings with her characteristic self-disguise in the form of photography. Marshall too takes inspiration from Old Masters, replacing the white protagonists with black ones. Who they are is unimportant. What matters is that they are inserted into the narrative of art history. Both artists sought to highlight the imbalances within art history. For Sherman, her cause is the underrepresentation of women artist and the ever-present male gaze. For Marshall, it is the absence of black artists and black subjects.

Marshall’s work very unabashedly points out the undemocratic nature of the art world. However, rather than fight against this flaw, he studies the systems in which he hopes his art will function and introduces black figures and black narratives so as to overcome this lack of democracy. The goal, which has undoubtedly been achieved in “Mastry,” is to normalize viewers, artists, and art institutions to the image of the black figure within art history.

“Kerry James Marshall: Mastry” is on view at MOCA Los Angeles until July 3, 2017.

What's Your Reaction?

Annabel Keenan is a New York-based writer focusing on contemporary art, market reporting, and sustainability. Her writing has been published in The Art Newspaper, Hyperallergic, and Artillery Magazine among others. She holds a B.A. in Art History and Italian from Emory University and an M.A. in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center.